To understand clock-arithmetic, simply picture a clock-face with one hand and a big fat 0 in place of the 12. Now you can do some clock-arithmetic. For example, set the hour-hand to 5, then move on 4 hours. You’ve done this sum:

5 + 4 → 9

Now try 9 + 7. The hour-hand is already on 9, so move forward 7 hours:

9 + 7 → 4

Now try 3 + 8 + 1:

3 + 8 + 1 → 0

And 3 * 4:

4 * 3 = 4 + 4 + 4 → 0

That’s clock-arithmetic. But you’re not confined to 12-hour clocks. Here’s a 7-hour clock, where the 7 is replaced with a 0:

3 + 1 → 4

4 + 5 → 2

2 + 4 + 1 → 0

3 * 3 = 3 + 3 + 3 → 2

Another name for clock-arithmetic is modular arithmetic, because the clocks model the process of dividing a number by 12 or 7 and finding the remainder or residue — 12 or 7 is known as the modulus (and modulo is Latin for “by the modulus”).

5 + 4 = 9 → 9 / 12 = 0*12 + 9

(5 + 4) modulo 12 = 9

3 + 8 + 1 = 12 → 12 / 12 = 1*12 + 0

(3 + 8 + 1) modulo 12 = 0

19 / 12 = 1*12 + 7

19 mod 12 = 7

3 + 1 = 4 → 4 / 7 = 0*7 + 4

(3 + 1) mod 7 = 4

2 + 4 + 1 = 7 → 7 / 7 = 1*7 + 0

(2 + 4 + 1) mod 7 = 0

19 / 7 = 2*7 + 5

19 mod 7 = 5

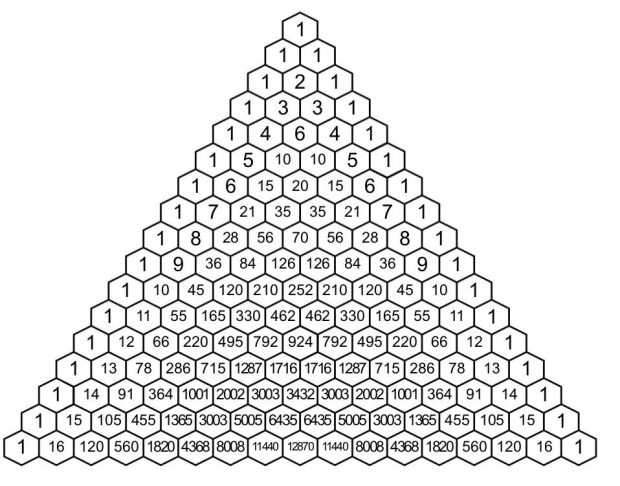

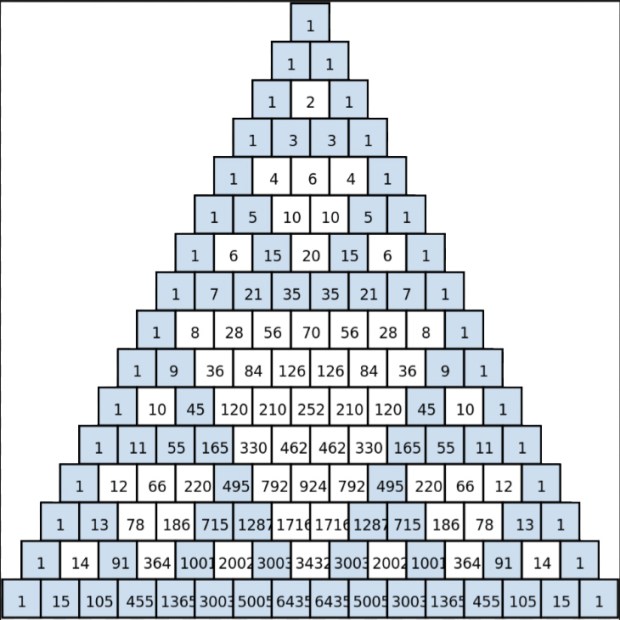

Modular arithmetic can do wonderful things. One small but beautiful example is the way it can uncover hidden fractals in Pascal’s triangle:

Pascal’s Triangle (via Desmos)

How to create Pascal’s triangle (via Wikipedia)

If you color all numbers n mod 2 = 1 (i.e., odd numbers) in the triangle, they create the famous Sierpiński triangle:

The Sierpiński triangle in Pascal’s triangle (via Fractal Foundation)

↓

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 2 = 1 (click for larger)

The Sierpiński triangle appears like this for all n mod 4 = 2 in Pascal’s triangle:

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 4 = 2 (click for larger)

And so on:

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 8 = 4

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 16 = 8

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 32 = 16

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 64 = 32

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 128 = 64

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 256 = 128

Pascal’s triangle, n mod 2,4,8… = 1,2,4… (animated via EzGif)

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum

There’s no need to calculate Pascal’s triangle in full to find the fractals above. The 10th row of Pascal’s triangle is this:

1, 10, 45, 120, 210, 252, 210, 120, 45, 10, 1

The 20th row is this:

1, 20, 190, 1140, 4845, 15504, 38760, 77520, 125970, 167960, 184756, 167960, 125970, 77520, 38760, 15504, 4845, 1140, 190, 20, 1

And the 29th is this:

1, 29, 406, 3654, 23751, 118755, 475020, 1560780, 4292145, 10015005, 20030010, 34597290, 51895935, 67863915, 77558760, 77558760, 67863915, 51895935, 34597290, 20030010, 10015005, 4292145, 1560780, 475020, 118755, 23751, 3654, 406, 29, 1

But you don’t need to consider those ever-growing numbers in the triangle when you’re finding fractals with modular arithmetic. When the modulus is 2, you just work with 0 and 1, that is, you add the previous numbers in the triangle and find the sum modulo 2. When the modulus is 4, you just work with 0, 1, 2 and 3, adding the numbers and finding the sum modulo 4. When it’s 8, you just work with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, finding the sum modulo 8. And so on.