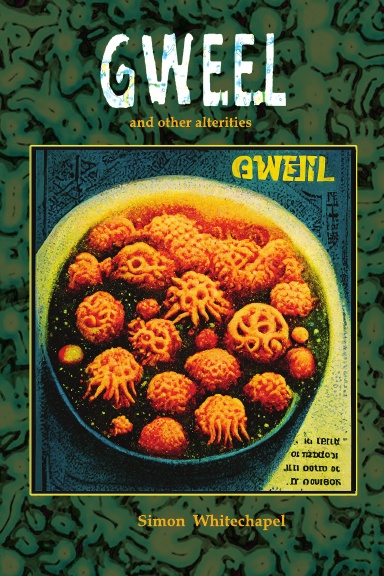

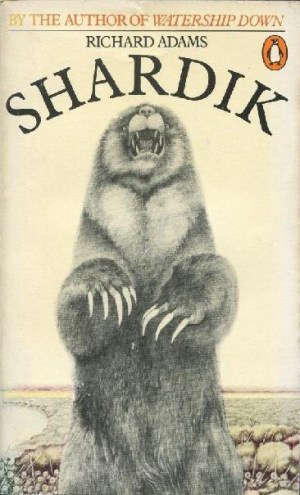

Shardik, Richard Adams (1974)

Shardik, Richard Adams (1974)

Is it thirty years since I last read Shardik? No, it think it’s nearer forty. But as I read the book in March this year I began remembering small things before I came to them again. And I realized how deep the characters and story had sunk into my mind on those early readings long ago. Indeed, I felt that coming across the book again in a second-hand shop had been important-with-a-capital-I, as though I’d been meant to meet it again now.

Maybe it wasn’t and maybe I hadn’t. But the opening chapters, in which the simple hunter Kelderek finds and helps to capture the giant bear Shardik, have been some of the most vivid and enjoyable literature I’ve ever read. Adams conjures the forest fire that drives Shardik, burned and near-dead, across the great river Telthearna; brings Kelderek and other characters to life with something like Dickensian vividness and depth; gives them a solid and scented world to inhabit; and evokes a genuine sense of matriarchal mystery and magic around the island of Quiso, where the Tuginda and her priestesses have awaited the return of Shardik for centuries. And Shardik himself is a huge and dangerous presence, slapping a leopard aside like a twig before he collapses and begins to die of his burns. He’s awesome even in his distress:

The bear was still lying among the scarlet trepsis, but already it looked less foul and wretched. Its great wounds had been dressed with some kind of yellow ointment. One girl was keeping the flies from its eyes and ears with a fan of fern-fronds, while another, with a jar of ointment, was working along its back and as much as she could reach of the flank on which it was lying. Two others had brought sand to cover patches of soiled ground which they had already cleaned and hoed with pointed sticks. The Tuginda was holding a soaked cloth to the bear’s mouth, as [Kelderek] himself had done, but was dipping it not in the pool but in a water-jar at her feet. The unhurried bearing of the girls contrasted strangely with the gashed and monstrous body of the creature they were tending. Kelderek watched them pause in their work, waiting as the bear stirred restlessly. Its mouth gaped open and one hind leg kicked weakly before coming to rest once more among the trepsis. – end of chapter 10 in Book I, “Ortelga”

If Shardik continued like that, I think it would be much better-known today. But it doesn’t. It turns not just grimmer, but less well-written and less psychologically plausible. The simple hunter Kelderek, friend of children and awestruck acolyte of Shardik, turns into a ruthless priest-king who cages his bear-god and oversees a trade in child-slaves to finance a war of attrition against the enemies of his tribe. And that small and impoverished tribe, from the half-forgotten river-island of Ortelga in the far north, has overthrown an empire by then. Shardik has given them victory, becoming a literal deus ex machina in a crucial early battle. Or perhaps that should be deus in machina:

Suddenly a snarling roar, louder even than the surrounding din of battle, filled the tunnel-like roadway under the trees. There followed a clanging and clattering of iron, sharp cracks of snapped wood, panic cries and a noise of dragging and scraping. Baltis’ voice shouted, “Let go, you fools!” Then again broke out the snarling, full of savagery and ferocious rage. Kelderek leapt to his feet.

The cage had broken loose and was rushing down the hill, swaying and jumping as the crude wheels ploughed ruts in the mud and struck against protruding stones. The roof had split apart and the bars were hanging outwards, some trailing along the ground, others lashing sideways like a giant’s flails. Shardik was standing upright, surrounded by long, white splinters of wood. Blood was running down one shoulder and he foamed at the mouth, beating the iron bars around him as Baltis’ hammers had never beaten them.

The point of a sharp, splintered stake had pierced his neck and as it swayed up and down, levering itself in the wound, he roared with pain and anger. Red-eyed, frothing and bloody, his head smashing through the flimsy lower branches of the trees overhanging the track, he rode down upon the battle like some beast-god of apocalypse. – Book I, ch. 22, “The Cage”

I don’t like that “splintered stake … levering itself in the wound.” It seems gratuitous. And that kind of thing doesn’t stop. Shardik suffers from beginning to end of the book and at times I felt as though he’d become little more than a punch-bag for the plot. Although many readers will come to this book as young fans of Watership Down (1972), I don’t think it’s a good book for children. There are cruelty and ruthlessness in Watership Down, but they don’t overwhelm the story as they come to do in Shardik. And the characters who suffer in Watership Down are rabbits; in Shardik, they’re children and a giant bear. There was one act of cruelty that struck me with horror when I read it as a teenager, because it suddenly and ruthlessly smashed the hope I had invested in a character.

I barely noticed the incident this time, because I knew it was coming and because I wasn’t captivated by Adams’ prose any more. He starts the book well, but his best here isn’t as good as his best in Watership Down. And his prose gets much less good after Book I. Plus, I could see his influences more clearly: classical myth and history, the Bible, Dickens. The book begins with these lines from Homer:

οἴκτιστον δὴ κεῖνο ἐμοῖς ἴδον ὀφθαλμοῖσι

πάντων, ὅσσ᾽ ἐμόγησα πόρους ἁλὸς ἐξερεείνων.

They’re not translated, but they mean:

It was the most pitiable sight of all I saw exploring the pathways of the sea. – Odyssey XII, 258

Homer’s influence hovers below the surface everywhere in Book I, sometimes bursting through in long and elaborate similes that don’t always work very well. But I think that something else that doesn’t always work very well is part of Adams’ linguistic cleverness rather than his clumsiness. Shardik is set in a fantasy universe with simple technology and some kind of magic. Like many writers before him and after, Adams creates new languages to go with his new world. The hunter Kelderek is nicknamed Zenzuata, meaning “Play-with-children”. Later he becomes Crendrik, the “Eye of God” and high-priest of Shardik, the “Power of God.” When he’s still a simple hunter he hears a song with the refrain “Senandril na kora, senandril na ro”; at another time he marvels at the beauty of a gold-and-purple bird called a kynat; at another he eats the ripe fruit of a tendriona on the island of Quiso, where the high-priestess is called the Tuginda and addressed with the honorific säiyett.

The strange names and words transport you from the here-and-now of reality to the elsewhere-and-elsewhen of fantasy. But what about Kabin, one of the cities of the Beklan Empire, and Deelguy, one of the lands bordering the Empire? Kabin echoes English “cabin” and Deelguy echoes English “deal” and “guy”. They don’t look or sound right (though perhaps Deelguy is meant to be pronounced “deel-goo-ee”). But that’s linguistic cleverness, I think. The paradox is that it’s not right if all the words and names of an invented language sound right to the ears of Anglophones. If they all sound right, that is, if they’re all exotic and alien, it means that they’ve been created with English in mind. So they’re a kind of un-English or anti-English, rather than something existing without any regard to English. In Shardik, it’s as though Kabin echoes English by chance, which is just what you might expect of a truly exotic and alien language. So that’s linguistic cleverness, I think.

And it’s also linguistically clever of Adams to invent an accent within the story for native speakers of Deelguy who are talking Beklan or Ortelgan. Here’s the slimy slave-trader Lalloc speaking to the chief villain of the story, the evil slave-trader Genshed: “I was in Kabin, Gensh, when the Ikats come north. Thought I had plonty of time to gotting back to Bekla, but left it too late – you ever know soldiers go so fost, Gensh, you ever know? Cot off, couldn’t gotting to Bekla […] no governor in Kabin – new governor, man called Mollo, been killed in Bekla, they were saying – the king kill him with his own honds – no one would take money to protect me.” (Book VI, ch. 51, “The Gap of Linsho”) The diminutive “Gensh” used by Lalloc is clever too. Genshed is a monster, but Lalloc thinks that the two of them are friends. His accent works as a kind of fantastic realism: yes, when someone from Deelguy spoke Beklan, he would speak in a strange way. And Adams captures that in English.

However, he puts words into the mouth of another character that are clumsy rather than clever: “the resources of this splendid establishment” (used of an inn); “riparian witch-doctor” (used of Kelderek); “bruin-boys [who] burst on an astonished world” (used of the followers of Shardik); “bear-bemused river-boys” (ditto); “some nice, lonely place with no propinquitous walls or boulders”; and so on. Those are the words of Elleroth, Ban of Sarkid, a “dandified” aristocrat who is secretly working against Kelderek and the Ortelgans. He’s an important character, central to the plot, so it’s a pity that, in part, he’s also a cliché out of old-fashioned boys’ literature. He’s a fop who’s also a fighter and whose languid, drawling irony covers serious purpose and emotion. It’s as though an Old Etonian or Harrovian has suddenly appeared. The way he’s presented is out of place in the fantasy universe of Shardik: “propinquitous” would work in one of Clark Ashton Smith’s Hyperborea stories. But it doesn’t work here as dialogue.

Another aspect of Elleroth’s character does work. Before he appears, we’ve seen Shardik through the eyes of his devoted followers, who swear “by the Bear” and see him triumph over all doubt and lead the Ortelgans to victory. After Elleroth appears, we suddenly see Shardik and his cult through the eyes of someone who despises “the bear” and his followers. To Elleroth, the Ortelgans are ursine swine. Later still, the perspective shifts in another way. The final chapters of the book are partly in the form of home-bound letters by an ambassador from Zakalon, a hitherto unknown land where they swear “by the Cat”. What is that about? What cult is practised in Zakalon? We never learn, but the glimpse of something beyond the story increases the power and reality of Shardik’s world.

And Shardik is, despite its frequent clumsiness, a powerful book. Sometimes its power is beautiful, sometimes it’s horrific, and new readers will remember both the beauty and the horror as I did in all the time that has passed since my last readings. Forty years on, I’m glad to have met it again, read it again, and re-acquainted myself with its power and its beauty. It isn’t as good as Watership Down, but it’s better than The Plague Dogs. And not many books are as good as Watership Down.

Elsewhere other-accessible…

• Sward and Sorcery – a review of Watership Down (1972)

• Paw is Less – a review of The Plague Dogs (1977)