What do you get if you list every successive pair of entries in this sequence?

1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 3, 1, 4, 3, 4, 1, 5, 2, 5, 3, 5, 4, 5, 1, 6, 5, 6, 1, 7, 2, 7, 3, 7, 4, 7, 5, 7, 6, 7, 1, 8, 3, 8, 5, 8, 7, 8, 1, 9, 2, 9, 4, 9, 5, 9, 7, 9, 8, 9, 1, 10, 3, 10, 7, 10, 9, 10, 1, 11, 2, 11, 3, 11, 4, 11, 5, 11, 6, 11, 7, 11, 8, 11, 9, 11, 10, 11, 1, 12, 5, 12, 7, 12, 11, 12, 1, 13, … — A038568 at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequence

You get the rational fractions ordered by denominator in their simplest form: 1/2, 1/3, 2/3, 1/4, 3/4, 1/5, 2/5, 3/5… There are no pairs like 2/4 and 5/35, because those can be simplified: 2/4 → 1/2; 15/35 → 3/7. You can get the same set of rational fractions by listing every successive pair in this sequence, the Stern-Brocot sequence:

1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 3, 1, 4, 3, 5, 2, 5, 3, 4, 1, 5, 4, 7, 3, 8, 5, 7, 2, 7, 5, 8, 3, 7, 4, 5, 1, 6, 5, 9, 4, 11, 7, 10, 3, 11, 8, 13, 5, 12, 7, 9, 2, 9, 7, 12, 5, 13, 8, 11, 3, 10, 7, 11, 4, 9, 5, 6, 1, 7, 6, 11, 5, 14, 9, 13, 4, 15, 11, 18, 7, 17, 10, 13, 3, 14, 11, 19, 8, 21, 13, 18, 5, 17, 12, 19, … — A002487 at the OEIS

But the fractions don’t come ordered by denominator this time. In fact, they seem to come at random: 1/2, 1/3, 2/3, 1/4, 3/5, 2/5, 3/4, 1/5, 4/7, 3/8, 5/7, 2/7, 5/8… But they’re not random at all. There’s a complicated way of generating them and a simple way. An amazingly simple way, I think:

Moshe Newman proved that the fraction a(n+1)/a(n+2) can be generated from the previous fraction a(n)/a(n+1) = x by 1/(2*floor(x) + 1 – x). The successor function f(x) = 1/(floor(x) + 1 – frac(x)) can also be used. — A002487, “Stern-Brocot Sequence”, at the OEIS

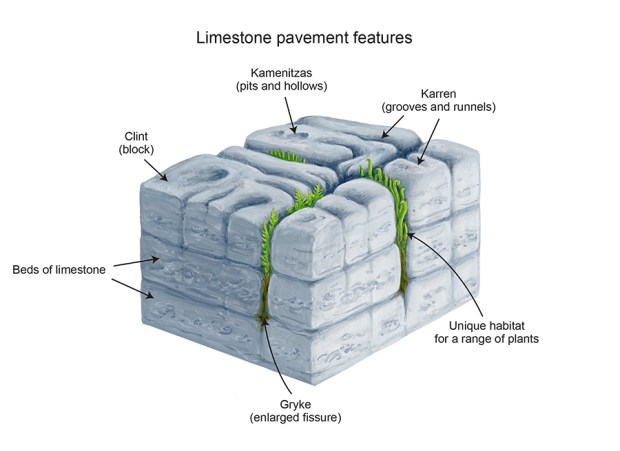

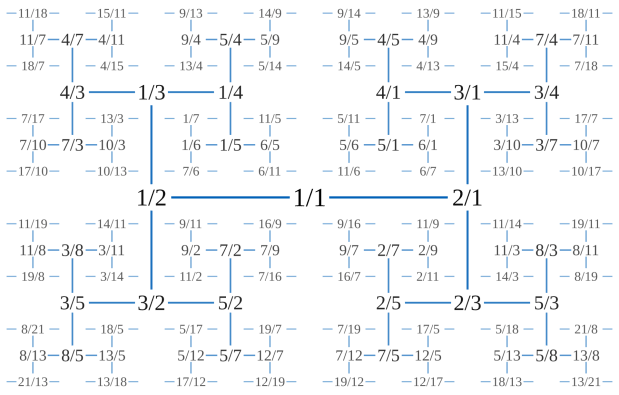

In another form, the Stern-Brocot sequence is generated by what’s called the Calkin-Wilf Tree. Now suppose you use the Stern-Brocot sequence to supply the x co-ordinate of an L-graph whose arms run from 0 to 1. And you use the Calkin-Wilf Tree to supply the y co-ordinate of the L-tree. What do you get? As I described in “I Like Gryke”, you get this fractal:

Limestone fractal

I call it a limestone fractal or pavement fractal or gryke fractal, because it reminds me of the fissured patterns you see in the limestone pavements of the Yorkshire Dales:

Fissured limestone pavement, Yorkshire Dales (Wikipedia)

But what happens when you plot the (x,y) of the Stern-Brocot sequence and the Calkin-Wilf Tree on a circle instead? You get an interestingly distorted limestone fractal:

Limestone fractal on circle

You can also plot the (x,y) around the perimeter of a polygon, then stretch the polygon into a circle. Here’s a square:

Limestone fractal on square

⇓

Limestone square stretched to circle

And here are a pentagon, hexagon, heptagon and octagon — note the interesting perspective effects:

Limestone fractal on pentagon

⇓

Limestone pentagon stretched to circle

Limestone fractal on hexagon

⇓

Limestone hexagon stretched to circle

Limestone fractal on heptagon

⇓

Limestone heptagon stretched to circle

Limestone fractal on octagon

⇓

Limestone octagon stretched to circle

And finally, here are animations of limestone polygons stretching to circles:

Limestone square stretched to circle (animated at EZgif)

Limestone pentagon to circle (animated)

Limestone hexagon to circle (animated)

Limestone heptagon to circle (animated)

Limestone octagon to circle (animated)

Previously Pre-Posted (Please Peruse)

• I Like Gryke — a first look at the limestone fractal