I think Britain would be much better off without three things that start with “c”: cars, canines, and coos (sic (i.e., pigeons)). But perhaps I should add another c-word to the list: cats. I like cats, but there’s no doubt that, in terms of issues around negative components/aspects of conservation/bio-diversity issues vis-à-vis the feline community/demographic, they’re buggers for killing wildlife:

A recent survey by the Mammal Society was based on a sample of 1,000 cats, countrywide, over the summer of 1997. The results included only “what the cat brought in” and ignored what it ate or left outside. Leaving aside this substantial hidden kill, it still concluded that cats killed about 230,000 bats a year. This is equivalent to more than the entire population of any species other than the two most common pipistrelles. If these 1,000 cats are typical, and there is no reason to believe that they are not, cats kill many more bats than all natural predators combined. They are one of the biggest causes of bat mortality in Britain, perhaps the biggest. (Op. cit., chapter 6, “Conservation”, pg. 139)

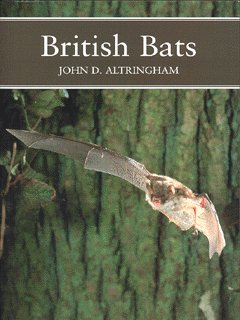

That is the unhappy conclusion in John D. Altringham’s very interesting and educative book British Bats (HarperCollins, 2003). Accordingly, I’d rather have fewer cats and more bats. Anyone but a cat-fanatic – and cat-fanatics are found in one or two places – should feel the same, and even the fanatics might reconsider if they read this book. The cat family contains some of the most beautiful and athletic animals on earth; the bat family contains some of the strangest and most interesting. In fact, all bats are strange: they’re mammals capable of sustained powered flight. Little else unites them: in chapter two, Altringham describes the huge variety of bats around the world. They live in many places and live off many things. Some drink nectar, some drink blood; some eat fruit, some eat fish. Some roost in caves, some in trees. Some hibernate, some migrate. Some use echolocation and some don’t. Bats are much more varied than cats and scientifically speaking are much more interesting.

Although echolocation isn’t universal, it is the most interesting aspect of bats’ behaviour and it’s used by all the species found in Britain, from the big ones, like the noctule and greater horseshoe bat, Nyctalus noctula and Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, to the small ones, like the whiskered bat and the pipistrelles, Myotis mystacinum and Pipistrellus spp.[1] Two of the pipistrelles are in fact most easily distinguished by the frequencies they call at: the 45 kHz pipistrelle, Pipistrellus pipistrellus, and the 55 kHz pipistrelle, Pipistrellus pygmaeus. As their English names suggest, one calls at an average of 45 kilo-Herz, or 45,000 cycles a second, and the other at an average of 55. The two species weren’t recognized as separate until recently: they look almost identical, although the 55 kHz is “on average… very slightly smaller”, and they forage for food in the same places, although the 55 kHz is “more closely associated with riparian habitat” (that is, it feeds more over rivers and other bodies of water). But examine their calls on a spectrograph, an electronic instrument for visually representing sounds, and there’s a much more obvious difference. This is a good example of how much the scientific study of bats depends on technology. Human beings didn’t need science to know about and understand the ways a cat uses its senses, because they’re refinements of what we use ourselves. We might marvel at the acuity of a cat’s eyes or ears, as we might marvel at the acuity of a dog’s nose, but we know for ourselves what seeing, hearing, and smelling are like.

Echolocation is something different. Bats don’t just see with their ears, as it were: they illuminate with their mouths, pouring out sound to detect objects around them. And the sound has to be very loud: “The intensity of a pipistrelle’s call, measured 10 centimetres in front of it, is as much as 120 decibels: that is the equivalent of holding a domestic smoke alarm to your ear.”[2] The “inverse square law”, whereby the intensity of sound (or light) falls in ratio to the square of the distance it travels, means that the returning echoes are far, far fainter than the original call. It’s as though Motörhead, playing at full volume, could hear someone at the back of the crowd unwrapping a toffee. How do bats call very loudly and hear very acutely? How do they avoid deafening themselves and drowning their own echoes? These are some of the questions bat-researchers have investigated and Altringham gives a fascinating summary of the answers. For example, they avoid deafening themselves by switching off their ears as they call. They’ve had to solve many other tricky acoustic problems to perfect their powers of echolocation.

Or rather evolution has had to solve the problems. The DNA of bats has changed in many ways as they evolved from the common mammalian ancestor (which also gave rise to you, me, and the author of this book) and those changes in DNA represent changes in their neurology, anatomy, and appearance. It’s easy to see that hearing is important for bats, because their eyes are relatively small and their ears are often large and rigid and come in a great variety of shapes. What isn’t easy to see is what those ears are supplying: the bat-brain and its astonishing ability to process and classify sound-data as though it were light-data. Bats can create sound-pictures of their surroundings in complete darkness. Of course, the feline or human ability to create light-pictures is astonishing too, but we’re too familiar with it to remember that easily. Bats aren’t just marvels in themselves: they should encourage us to marvel at ourselves and what our own brains can do. The digestive system of a bat, cat, or human needs food; the nervous system of a bat, cat, or human needs data. That’s what our sense-organs are there for and in principle it doesn’t matter whether we create a picture of the world with our eyes or with our ears.

Male noctule calling from tree-roost

In practice, there are some very important differences between sound and light. Light works instantly and powerfully on a terrestrial scale; sound takes its time and is much more easily diluted or blocked. A hunting cat can scan an illuminated or unilluminated environment for free, because it doesn’t have to generate the light it sees by or the sound it hears by. Hunting bats have to pay when they scan their environment, because they’re using energy to create sound and induce echoes. Once they’ve got their data, both cats and bats have to pay to process it: it takes energy to run a brain. But bat-brains are solving more complicated problems than cat-brains: Altringham describes the questions a flying bat has to answer when it detects the echo of an insect:

How far away is the insect?… How big is it?… In which direction does it lie?… How fast is it flying and in what direction?… What is it?… (ch. 3, “The Biology of Temperate Bats”, pp. 42-3)

Like insect-eating birds, bats can answer all these questions in mid-flight, but what is relatively easy for birds, using their eyes, is a much greater computational problem for bats, using their ears. “Computational” is the key word: brains are mathematical mechanisms and process sense-data using algorithms that run on chemicals and electricity. Bats were intuitively using mathematical concepts like doppler shift and frequency modulation (as in FM radio) millions of years before man invented mathematics, but man-made mathematics is an essential tool in the study of echolocation. For example, the concept of wavelength, or the distance between one crest of a sound-wave and the next, is very important in understanding how bats perceive objects. Light has very short wavelengths, so humans and other visual animals can easily resolve small objects. Sound has much longer wavelengths, so bats find it hard to resolve small objects. But some find it harder than others: Daubenton’s bat, Myotis daubentonii, and other Myotis spp. “can resolve distances down to about 5 millimetres when given tasks to perform in the laboratory”. But horseshoe bats, Rhinolophus spp., “can do little better than 12 millimetres.”

Why this difference? You have to look at the nature of the sound being produced by the different species: the Myotis spp. use “high frequency FM calls”; the Rhinolophus use “predominantly CF [constant frequency] calls”. The mathematical nature of the call determines the bats’ powers of perception. Calls can also determine how easily a bat can identify an insect: “relatively long calls can have a ‘flutter detector’… If a call is 50 milliseconds long, then within one echo a bat can detect the full wingbeat of insects beating their wings at more than 50 Hz.”[3] So bats can tell one kind of insect from another, something like the way a blindfolded human can tell a bumblebee from a mosquito. But insects aren’t passive as prey and one of the most interesting sections of the book describes how they try to avoid being eaten. Some moths have “ultrasound detectors” and if a moth hears a calling bat, it “will either stop flying and drop toward the ground, or begin a series of rapid and unpredictable manoeuvres involving dives, loops and spirals”.[4] This kind of ecological interaction creates an “evolutionary arms race”: each side evolves to become better at capture or evasion.

The moth/bat air-battle is reminiscent of the air-battles of the Second World War, which involved radar trying to detect bombers and bombers trying to evade radar. One defensive technique was jamming, or attempts to interfere with radar signals or drown them in noise. Some moths may use this technique too. The tiger moths, the Arctiidae, don’t try to escape detection. Instead, they “emit their own, loud clicks”[5], perhaps to interfere with echolocation or startle a predatory bat. Alternatively, Altringham suggests, the clicks may be the aural equivalent of “bright warning colours and patterns”: the moths may be warning bats of their unpalatability. If so, it would be another example of the difference between the costs of sight and the costs of sound. An unpalatable insect in daylight doesn’t have to pay for its warning colours, after the initial investment of creating them, and doesn’t have to know when a predator is watching. An unpalatable insect in the dark, on the other, can’t send out a constant audible warning: it has to select its moment and know when a predator is nearby. Unless, that is, some insects use passive signals of unpalatability, like body modifications that create a distinctive echo.

Bat-researchers don’t know the full story: there is still a lot to learn about bats’ hunting techniques and the ways insects try to defeat them. But “cost” is a word that comes up again and again in this book, which is partly a study in bio-economics. Bats have to pay a lot for echolocation and flight, but flight is a more general phenomenon in the animal kingdom, so the economics of bat flight also illuminates (insonates?) bird and insect flight. Altringham points out a very important but not very obvious fact: that flight is expensive by the unit of time and cheap by the unit of distance. Movement on foot is the opposite: it’s expensive by the unit of distance and cheap by the unit of time. Bats, birds, and insects expend more energy per second in flight, but can travel further and faster in search of food or new habitats. However, bats don’t all fly in the same way: a bat expert can identify different species by their wings alone. The wings vary in “wing loading”, which is “simply the weight of the bat divided by the total area of its wings. Bats with a high wing loading are large and heavy in relation to their wing area, bats with small bodies and large wings have a low wing loading”.[6] Then there’s “aspect ratio”, the “ratio of wingspan to average wing width”, or, because “bats have such an irregular wing shape”, “wingspan squared divided by wing area.”

It’s mathematics again: there are no explicit numbers in a bat’s life, but everything it does, from echolocating to flying, from eating to mating, is subject to mathematical laws of physics, ecology, and economics. Bats have to invest time and energy and make a profit to survive and have offspring. As warm-blooded, fast-moving animals with high energy needs, they’re usually nearer famine than feast, which is one reason they migrate or hibernate to avoid or survive through cold weather and scarcity. They also vary their diet during the year, to take advantage of changes in the abundance of one insect species or another, and seek out specialized feeding niches. Daubenton’s bat, for example, “habitually feeds very low over water”, using echolocation to catch not just flying insects but floating ones too. That is why it needs smooth water to feed over: ponds, lakes, canals and placid streams and rivers. The floating insects are easier to echolocate on a smooth surface, rather like, for humans, a black spider on a white wall. Once spotted, they “are gaffed with the large feet or the tail mechanism and quickly transferred to the mouth as the bat continues its flight”.[7]

Long-eared bat gleaning harvestman

One of the photos in the colour section in the middle of the book shows a Daubenton’s bat mirrored in smooth water, having just scooped up prey from the surface. Other photos show other species roosting, perching, or in flight, but the book also has excellent black-and-white illustrations mixed with the text, hand-drawn using a speckled or pointillist technique that suits bats very well. I particularly like the drawings on pages 48, 67 and 101. The first shows a long-eared bat, Plecotus auritus, “gleaning”, or snapping up, a “harvestman” (a long-legged relation of the spiders) from a leaf (ch. 3); the second shows a “male noctule calling from his tree roost to attract mates” (ch. 3); and the third shows a tawny owl trying to catch another long-eared bat (ch. 4).

Owls could be called the avian equivalents of bats: they’re specialized nocturnal hunters with very sharp hearing, but I think they’re both less interesting and more attractive. Bats, with their leathery wings, sometimes huge ears, and oddly shaped noses, are strange rather than attractive and some people find them repulsive. But some people, or peoples, find them divine or lucky: the introduction describes the Mayan bat-god Zotz, with his leaf-shaped nose modelled on that of the phyllostomids, or vampire bats.[8] The Chinese use a ring of five bats to symbolize the “five great happinesses: health, wealth, good luck, long life and tranquillity.”[9] Altringham blames the less positive image of bats in European cultures partly on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which was first published in 1897. Before then, he says, “bats were not linked with witches, vampires and the evil side of the supernatural in any significant way.”[10] Dracula may have done for bats what the novel Jaws (1974) and its cinematic offspring did for sharks: encouraged human beings to harm the animal fictionally and falsely depicted as villainous.

Roosting Daubenton’s bats

If so, British Bats is partly redressing the balance. You can learn a lot from this book about both biology in general and bat-biology in particular. It stimulates the mind, pleases the eye, describes the appearance, ecology, and range of all British species, and points the way to further reading and research. So let’s not hear it for John D. Altringham! Without specialized equipment, that is, but that equipment is getting cheaper and more widely available all the time: you don’t have to be a professional zoologist to record and analyse bat-calls any more. There is still a lot for zoologists, both amateur and professional, to learn about bats. Okay, some of the research – like fitting miniature radio-transmitters to wild bats – seems intrusive and smacks of Weber’s Entzauberung, or “disenchantment”, but the more we know about bats, the more we will be able to help conserve them and their habitats. Bats aren’t villains: cats are. I like both kinds of mammal, but I hope we can find some way in future to help stop the latter preying so heavily on the former. If this book helps publicize the problem, it will be valuable for bat-conservation just as it is already valuable for bat-science. In short, no more brick-bats for Brit-bats: we should control our cats better.

Reviewer’s note: Any scientific mistakes, misinterpretations or misunderstandings in this review are entirely your responsibility.

NOTES

1. sp = species, singular; spp = species, plural.

2. ch. 3, “The Biology of Temperate Bats”, pg. 40

3. Ibid., pg. 45

4. ch. 4, “An Ecological Synthesis”, pg. 98

5. Ibid., pg. 99

6. Ibid., pg. 71

7. ch. 5, “British Bats, Past and Present”, pg. 117

8. ch. 1, “Introduction”, pg. 10. “Phyllostomid” is scientific Greek for “leaf-mouthed clan”.

9. Ibid., pg. 11

10. Ibid., pg. 9

Grasses, Ferns, Mosses and Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland, Roger Phillips (1980)

Grasses, Ferns, Mosses and Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland, Roger Phillips (1980)