John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-93), Autumn Morning.

Tag Archives: painting

Jewels in the Skull

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

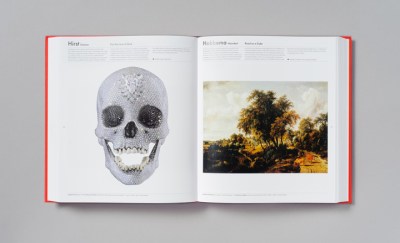

An A to Z of artists, mostly painters, occasionally sculptors, installers and performers, with a few photographers and video-makers too. You can trace the development, culmination and corruption of high art all the way from Giotto and Fra Angelico through Van Eyck and Caravaggio to Auerbach and Twombly. But the modernist dreck heightens the power of the pre-modernist delights. A few pages after Pieter Claesz’s remarkable A Vanitas Still Life of 1645 there’s Joseph Cornell’s “Untitled” of 1950. One is a skull, watch and overturned glass, skilfully lit, minutely detailed, richly symbolic; the other is a wooden box containing a “frugal assortment of stamps, newspaper cuttings and other objects with no particular relevance to each other”. From the sublime to the slapdash. Over the page from Eleazar Lissitzky’s Composition of 1941 there’s Stefan Lochner’s The Virgin and Child in a Rose Arbour of 1442. One is like a child’s doodle, the other like a jewel. From the slapdash to the sublime.

And so it goes on throughout the book, with beautiful art by great artists following or preceding ugly art by poseurs and charlatans. But some of the modern art is attractive or interesting, like Bridget Riley’s eye-alive Cataract 3 (1961) and Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God (2006). Riley and Hirst aren’t great and Hirst at least is more like an entrepreneur than an artist, but their art here is something that rewards the eye. So is Riley’s art elsewhere, as newcomers to her work might guess from the single example here. That is one of the purposes of a guide like this: to invite – or discourage – further investigation. I vaguely remember seeing the beautiful still-life of a boiled lobster, drinking horn and peeled lemon on page 283 before, but I wouldn’t have recognized the name of the Dutch artist: Willem Kalf (1619-93).

Willem Kalf, Still Life (c. 1653)

Elsewhere, I was surprised and pleased to see an old favourite: John Atkinson Grimshaw and his Nightfall on the Thames (1880). Many more people know Grimshaw’s atmospheric and eerie art than know his name, because it often appears on book-covers and as illustrations. If Phaidon are including him in popular guides with giants like Da Vinci, Dürer, Raphael and Titian, perhaps he’ll return to his previous fame. I certainly hope so.

Finding Grimshaw here made a good guide even better. The short texts above each art-work pack in a surprising amount of information and anecdote too. What you learn from the texts raises some interesting questions. For example: Why has one small nation contributed so much to the world’s treasury of art? From Van Eyck to Van Gogh by way of Hieronymus Bosch and Jan Vermeer, Holland is comparable to Italy in its importance. But only in painting, not sculpture or architecture. There aren’t just patterns of pigment, texture and geometry in this book: there are patterns of DNA, culture and evolution too. Brilliant, beautiful and banal; skilful, subtle and slapdash: The Art Book has all that and more. It puts jewels inside your skull.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• Ai Wei to Hell — How to Read Contemporary Art, Michael Wilson

• Eyck’s Eyes — Van Eyck, Simone Ferrari

• Face Paint — A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, Laura Cumming

Performativizing Papyrocentricity #23

Papyrocentric Performativity Presents:

• Face Paint – A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, Laura Cumming (HarperPress 2009; paperback 2010)

• The Aesthetics of Animals – Life: Extraordinary Animals, Extreme Behaviour, Martha Holmes and Michael Gunton (BBC Books 2009)

• Less Light, More Night – The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artifical Light, Paul Bogard (Fourth Estate 2013)

• The Power of Babel – Clark Ashton Smith, Huysmans, Maupassant

Or Read a Review at Random: RaRaR

Young at Art

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna.

Cat out of Bel

The Belgian symbolist Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) is one of my favourite artists; Caresses (1896) is one of his most famous paintings. I like it a lot, though I find it more interesting than attractive. It’s a good example of Khnopff’s art in that the symbols are detached from clear meaning and float mysteriously in a world of their own. As Khnopff used to say: On n’a que soi – “One has only oneself.” But he was clearly inspired by the story of Oedipus and the Sphinx, which is thousands of years old. Indeed, an alternate title for the painting is The Sphinx.

Even older than the Oedipus story is another link to the incestuous themes constantly explored by Khnopff, who was obsessed with his sister Marguerite and portrayed her again and again in his art. That’s her heavy-jawed face rubbing against the heavy-jawed face of the oddly nippled man, but Khnopff has given her the body of a large spotted felid. Many people misidentify it as a leopard, Panthera pardus. It’s actually a stranger and rarer felid: a cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus, which occupies a genus of its own among the great cats. And A. jubatus, unlike P. pardus, is an incestuous animal par excellence:

Cheetahs are very inbred. They are so inbred that genetically they are almost identical. The current theory is that they became inbred when a “natural” disaster dropped their total world population down to less than seven individual cheetahs – probably about 10,000 years ago. They went through a “Genetic Bottleneck”, and their genetic diversity plummeted. They survived only through brother-to-sister or parent-to-child mating. (Cheetah Extinction)

It must have been a large disaster. Perhaps cheetahs barely survived the inferno of a strike by a giant meteor, which would make them a cat out of hell. In 1896, they became a cat out of Bel too when Khnopff unveiled Caresses. Back then, biologists could not analyse DNA and discover the ancient history of a species like that. So how did Khnopff know the cheetah would add extra symbolism to his painting? Presumably he didn’t, though he must have recognized the cheetah as unique in other ways. All the same, I like to think that perhaps he had extra-rational access to scientific knowledge from the future. As he dove into the subconscious, Khnopff used symbols like weights to drag himself and his art deeper and darker. So perhaps far down, in the mysterious black, where time and space lose their meaning, he encountered a current of telepathy bearing the news of the cheetah’s incestuous nature. And that’s why he chose to give his sphinx-sister a cheetah’s body.

Roses Are Golden

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s painting The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888) is based on an apocryphal episode in the sybaritic life of the Roman Emperor Elagabalus (204-222 A.D.), who is said to have suffocated guests with flowers at one of his feasts. The painting is in a private collection, but I saw it for real in an Alma-Tadema exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool sometime during the late 1990s. I wasn’t disappointed: it was a memorable meeting with a painting I’d been interested in for years. Roses is impressively large and impressively skilful. Close-up, the brush-strokes are obvious, obtrusive and hard to interpret as people and objects. It isn’t till you step back, far beyond the distance at which Alma-Tadema was painting, that the almost photographic realism becomes apparent. But you get more of the many details at close range, like the Latin inscription on a bowl below and slightly to the right of that scowling water-mask. Alas, I forgot to take a note of what the inscription was, though perhaps the memory is still locked away somewhere in my subconscious.

Whatever it is, I feel sure it is significant, because Roses is rich with meaning. That’s a large part of why I’m interested in it. Yes, I like it a lot as art, but the women would have to be more attractive for it to be higher in the list of my favourite paintings. As it is, I think there are only four reasonably good-looking people in it: the man with the beard on the right; the flautist striding past the marble pillar on the left; the red-headed girl with a crown of white flowers; and Heliogabalus himself, crowned in roses and clutching a handful of grapes beside the overweight man who’s wearing a wreath and sardonically saluting one of the rose-pelted guests in the foreground. When I first wrote about Roses in a pub-zine whose name escapes me, I misidentified the overweight man as Heliogabalus himself, even though I noted that he seemed many years old than Heliogabalus, toppled as a teen tyrant, should have been. It was a bad mistake, but one that, with less knowledge and more excuse, many people must make when they look at Roses, because the overweight man and his sardonic salute are a natural focus for the eye. Once your eye has settled on and noted him, you naturally follow the direction of his gaze down to the man in the foreground, who’s gazing right back.

And by following that gaze, you’ve performed a little ratio-ritual, just as Alma-Tadema intended you to do. Yes, Roses is full of meaning and much of that meaning is mathematical. I think the angle of the gaze is one of many references in Roses to the golden ratio, or φ (phi), a number that is supposed to have special aesthetic importance and has certainly been used by many artists and musicians to guide their work. A rectangle with sides in the proportions 8:13, for example, approximates the golden ratio pretty closely, but φ itself is impossible to represent physically, because it’s an irrational number with infinitely many decimal digits, like π or √2, the square root of two. π represents the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter and √2 the ratio of a square’s diagonal to its side, but no earthly circle and no earthly square can ever capture these numbers with infinite precision. Similarly, no earthly rectangle can capture φ, but the rectangle of Roses is a good attempt, because it measures 52″ x 84 1/8". That extra eighth of an inch was my first clue to the painting’s mathematical meaningfulness. And sure enough, 52/84·125 = 416/673 = 0·61812…, which is a good approximation to φ’s never-ending 0·6180339887498948482045868343656…*

That deliberate choice of dimensions for the canvas led me to look for more instances of φ in the painting, though one of the most important and obvious might be called a meta-presence. The Roses of Heliogabalus is dated 1888, or 1666 years after the death of Heliogabalus in 222 AD. A radius at 222º divides a circle in the golden ratio, because 222/360 = 0·616… It’s very hard to believe Alma-Tadema didn’t intend this reference and I also think there’s something significant in 1888 itself, which equals 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 59 = 25 x 59. Recall that 416 is the expanded short side of Roses. This equals 25 x 13, while 673, the expanded long side, is the first prime number after 666. As one of the most technically skilled painters who ever lived, Alma-Tadema was certainly an exceptional implicit mathematician. But he clearly had explicit mathematical knowledge too and this painting is a phi-pie cooked by a master matho-chef. In short, when Roses is read, Roses turns out to be golden.

*φ is more usually represented as 1·6180339887498948482045868343656…, but it has the pecularity that 1/φ = φ-1, so the decimal digits don’t change and 0·6180339887498948482045868343656… is also legitimate.

Appendix I

I’ve looked at more of Alma-Tadema’s paintings to see if their dimensions approximate φ, √2, √3 or π, or their reciprocals. These were the results (ε = error, i.e. the difference between the constant and the ratio of the dimensions).

The Roman Wine Tasters (1861), 50" x 69 2/3": 150/209 = 0·717… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·02)

A Roman Scribe (1865), 21 1/2" x 15 1/2": 43/31 = 1·387… ≈ √2 (ε=0·027)

A Picture Gallery (1866), 16 1/8" x 23": 129/184 = 0·701… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·012)

A Roman Dance (1866), 16 1/8" x 22 1/8": 43/59 = 0·728… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·042)

In the Peristyle (1866), 23" x 16": 23/16 = 1·437… ≈ √2 (ε=0·023)

Proclaiming Emperor Claudius (1867), 18 1/2" x 26 1/3": 111/158 = 0·702… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·009)

Phidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon Athens (1868), 29 2/3" x 42 1/3": 89/127 = 0·7… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·012)

The Education of Children of Clovis (1868), 50" x 69 2/3": 150/209 = 0·717… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·02)

An Egyptian Juggler (1870), 31" x 19 1/4": 124/77 = 1·61… ≈ φ (ε=0·007)

A Roman Art Lover (1870), 29" x 40": 29/40 = 0·725… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·034)

Good Friends (1873), 4 1/2" x 7 1/4": 18/29 = 0·62… ≈ φ (ε=0·006)

Pleading (1876), 8 1/2" x 12 3/8": 68/99 = 0·686… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·041)

An Oleander (1882), 36 1/2" x 25 1/2": 73/51 = 1·431… ≈ √2 (ε=0·017)

Dolce Far Niente (1882), 9 1/4" x 6 1/2": 37/26 = 1·423… ≈ √2 (ε=0·008)

Anthony and Cleopatra (1884), 25 3/4" x 36 1/3": 309/436 = 0·708… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·003)

Rose of All Roses (1885), 15 1/4" x 9 1/4": 61/37 = 1·648… ≈ φ (ε=0·03)

The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), 52" x 84 1/8": 416/673 = 0·618… ≈ φ (ε<0.001)

The Kiss (1891), 18" x 24 3/4": 8/11 = 0·727… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·039)

Unconscious Rivals (1893), 17 3/4" x 24 3/4": 71/99 = 0·717… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·019)

A Coign of Vantage (1895), 25 1/4" x 17 1/2": 101/70 = 1·442… ≈ √2 (ε=0·028)

A Difference of Opinion (1896), 15" x 9": 5/3 = 1·666… ≈ φ (ε=0·048)

Whispering Noon (1896), 22" x 15 1/2": 44/31 = 1·419… ≈ √2 (ε=0·005)

Her Eyes Are With Her Thoughts And Her Thoughts Are Far Away (1897), 9" x 15": 3/5 = 0·6… ≈ φ (ε=0·048)

The Baths of Caracalla (1899), 60" x 37 1/2": 8/5 = 1·6… ≈ φ (ε=0·018)

The Year’s at the Spring, All’s Right with the World (1902), 13 1/2" x 9 1/2": 27/19 = 1·421… ≈ √2 (ε=0·006)

Ask Me No More (1906), 31 1/2" x 45 1/2": 9/13 = 0·692… ≈ 1/√2 (ε=0·03)

Appendix II

The Roses of Heliogabalus is based on this section from Aelius Lampridius’ pseudonymous and largely apocryphal Vita Heliogabali, or Life of Heliogabalus, in the Historia Augusta (late fourth century):

XXI. 1 Canes iecineribus anserum pavit. Habuit leones et leopardos exarmatos in deliciis, quos edoctos per mansuetarios subito ad secundam et tertiam mensam iubebat accumbere ignorantibus cunctis, quod exarmati essent, ad pavorem ridiculum excitandum. 2 Misit et uvas Apamenas in praesepia equis suis et psittacis atque fasianis leones pavit et alia animalia. 3 Exhibuit et sumina apruna per dies decem tricena cottidie cum suis vulvis, pisum cum aureis, lentem cum cerauniis, fabam cum electris, orizam cum albis exhibens. 4 Albas praeterea in vicem piperis piscibus et tuberibus conspersit. 5 Oppressit in tricliniis versatilibus parasitos suos violis et floribus, sic ut animam aliqui efflaverint, cum erepere ad summum non possent. 6 Condito piscinas et solia temperavit et rosato atque absentato…

XXI. 1 He fed his dogs on goose-livers. He had pet lions and leopards, which had been rendered harmless and trained by tamers, and these he would suddenly order during the dessert and the after-dessert to get on the couches, thereby causing laughter and panic, for none knew that they were harmless. 2 He sent grapes from Apamea to his stables for the horses, and he fed parrots and pheasants to his lions and other beasts. 3 For ten days in a row, moreover, he served wild sows’ udders with the matrices, at a rate of thirty a day, serving, besides, peas with gold-pieces, lentils with onyx, beans with amber, and rice with pearls; 4 and he also sprinkled pearls on fish and used truffles instead of pepper. 5 In a banqueting-room with a reversible ceiling he once buried his parasites in violets and other flowers, so that some were actually smothered to death, being unable to crawl out to the top. 6 He flavoured his swimming-pools and bath-tubs with essence of spices or of roses or wormwood…