Phiday falls on the 11th, 12th and 23rd of each month, because 11, 12 and 23 represent entries in the famous Fibonacci sequence:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946, 17711, 28657, 46368, 75025, 121393, 196418, 317811, 514229, 832040, 1346269, 2178309, 3524578, 5702887, 9227465, 14930352, 24157817, 39088169, 63245986, 102334155, 165580141, 267914296, 433494437, 701408733, 1134903170, 1836311903, 2971215073, 4807526976, 7778742049, 12586269025, 20365011074, 32951280099, 53316291173, 86267571272, 139583862445, 225851433717, 365435296162, 591286729879, 956722026041, 1548008755920, 2504730781961, 4052739537881, 6557470319842, 10610209857723, 17167680177565, 27777890035288, 44945570212853, 72723460248141, 117669030460994, 190392490709135, 308061521170129, 498454011879264, 806515533049393, 1304969544928657, …

Successive entries in the Fibonacci sequence provide better and better approximations to the golden ratio or φ = 1.61803398874989484820458683…

2 = 2/1

1.5 = 3/2

1.6 = 5/3

1.6 = 8/5

1.625 = 13/8

1.6153846… = 21/13

1.619047619… = 34/21

1.6176470588235294117647… = 55/34

1.618… = 89/55

1.617977528… = 144/89

1.61805… = 233/144

1.618025751… = 377/233

1.618037135… = 610/377

1.618032786… = 987/610

1.618034447… = 1597/987

1.618033813… = 2584/1597

1.618034055… = 4181/2584

1.618033963… = 6765/4181

1.618033998… = 10946/6765

1.618033985… = 17711/10946

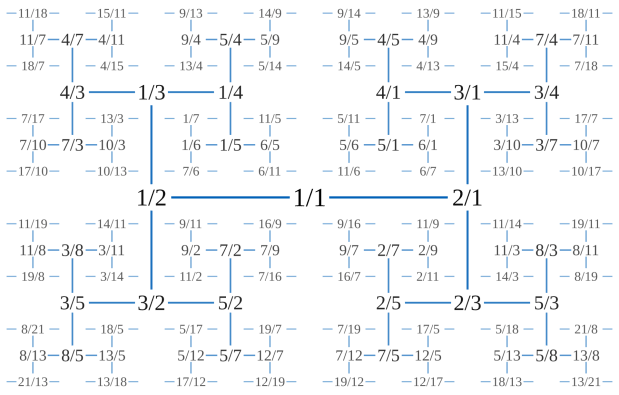

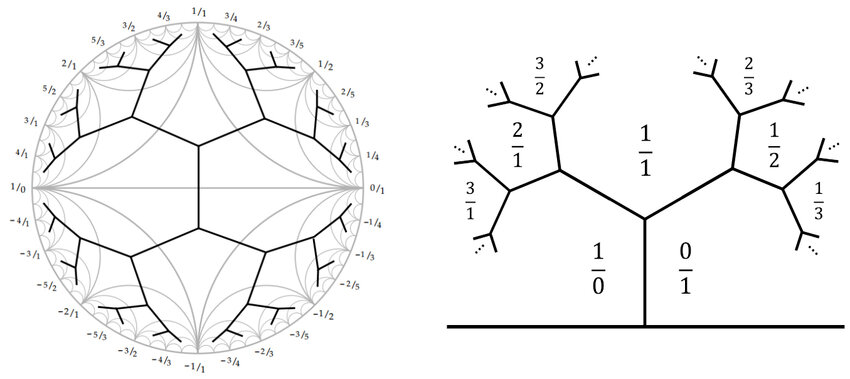

Today is 23rd June, so here’s a Fascinating Fibonacci Fact for Phiday. First, list the rational fractions < 1 in simplified form and mark the Fibonacci fractions:

1/2, 1/3, 2/3, 1/4, 3/4, 1/5, 2/5, 3/5, 4/5, 1/6, 5/6, 1/7, 2/7, 3/7, 4/7, 5/7, 6/7, 1/8, 3/8, 5/8, 7/8, 1/9, 2/9, 4/9, 5/9, 7/9, 8/9, 1/10, 3/10, 7/10, 9/10, 1/11, 2/11, 3/11, 4/11, 5/11, 6/11, 7/11, 8/11, 9/11, 10/11, 1/12, 5/12, 7/12, 11/12, 1/13, 2/13, 3/13, 4/13, 5/13, 6/13, 7/13, 8/13, 9/13, 10/13, 11/13, 12/13, 1/14, 3/14, 5/14, 9/14, 11/14, 13/14, 1/15, 2/15, 4/15, 7/15, 8/15, 11/15, 13/15, 14/15, 1/16, 3/16, 5/16, 7/16, 9/16, 11/16, 13/16, 15/16, 1/17, 2/17, 3/17, 4/17, 5/17, 6/17, 7/17, 8/17, 9/17, 10/17, 11/17, 12/17, 13/17, 14/17, 15/17, 16/17, 1/18, 5/18, 7/18, 11/18, 13/18, 17/18, 1/19, 2/19, 3/19, 4/19, 5/19, 6/19, 7/19, 8/19, 9/19, 10/19, 11/19, 12/19, 13/19, 14/19, 15/19, 16/19, 17/19, 18/19, 1/20, 3/20, 7/20, 9/20, 11/20, 13/20, 17/20, 19/20, 1/21, 2/21, 4/21, 5/21, 8/21, 10/21, 11/21, 13/21, 16/21, 17/21, 19/21, 20/21, 1/22, 3/22, 5/22, 7/22, 9/22, 13/22, 15/22, 17/22, 19/22, 21/22, 1/23, 2/23, 3/23, 4/23, 5/23, 6/23, 7/23, 8/23, 9/23, 10/23, 11/23, 12/23, 13/23, 14/23, 15/23, 16/23, 17/23, 18/23, 19/23, 20/23, 21/23, 22/23…

Next, record the positions in the fraction list of the FibFracs, i.e. pos(fibonacci(i)/fibonacci(i+1)) = pos(fibfrac(i)):

1, 3, 8, 20, 53, 135, 353, 924, 2422, 6311, 16529, 43229, 113066, 296173, 775286, 2029661, 5313844, 13911391, 36419909, 95348490, 249624578, 653521015, 1710943906, 4479312193, 11726939926, 30701521655, 80377560978, 210431191133, 550915866198, 1442316294349, 3776032465954, 9885782372588, 25881314454327, 67758160822605, 177393168080718, 464421339906882, 1215870841639593, …

What do you get when you divide pos(fibfrac(i+1)) by pos(fibfrac(i))?

pos(1/2) = 1

pos(2/3) = 3 (3/1 = 3)

pos(3/5) = 8 (8/3 = 2.6…)

pos(5/8) = 20 (20/8 = 2.5)

pos(8/13) = 53 (53/20 = 2.65)

pos(13/21) = 135 (2.5471698113207…)

pos(21/34) = 353 (2.6148…)

pos(34/55) = 924 (2.617563739376770538243626062…)

pos(55/89) = 2422 (2.621…)

pos(89/144) = 6311 (2.605697770437654830718414533…)

pos(144/233) = 16529 (2.619077800665504674378070037…)

pos(233/377) = 43229 (2.615342730957710690301893642…)

pos(377/610) = 113066 (2.615512734506928219482291980…)

pos(610/987) = 296173 (2.619470044045071020465922559…)

pos(987/1597) = 775286 (2.617679531895209894217231145…)

pos(1597/2584) = 2029661 (2.617951310871084993150914630…)

pos(2584/4181) = 5313844 (2.618094351716863062353762525…)

pos(4181/6765) = 13911391 (2.617952465296309037299551888…)

pos(6765/10946) = 36419909 (2.617991903182075753603647543…)

pos(10946/17711) = 95348490 (2.618032076906068051954770123…)

pos(17711/28657) = 249624578 (2.618023400265699016313735016…)

pos(28657/46368) = 653521015 (2.618015502463863954934758067…)

pos(46368/75025) = 1710943906 (2.618039614227248683043497844…)

pos(75025/121393) = 4479312193 (2.618035680358535377956453004…)

pos(121393/196418) = 11726939926 (2.618022459860278821159630657…)

pos(196418/317811) = 30701521655 (2.618033506501651708043379296…)

pos(317811/514229) = 80377560978 (2.618031831816708695313688353…)

pos(514229/832040) = 210431191133 (2.618034045479393794998913484…)

pos(832040/1346269) = 550915866198 (2.618033302153394031845776103…)

pos(1346269/2178309) = 1442316294349 (2.618033683260502304564996035…)

pos(2178309/3524578) = 3776032465954 (2.618033562227999267671331082…)

pos(3524578/5702887) = 9885782372588 (2.618034262608066669117450079…)

pos(5702887/9227465) = 25881314454327 (2.618034008728793003503058474…)

pos(9227465/14930352) = 67758160822605 (2.618033985181798482654668954…)

pos(14930352/24157817) = 177393168080718 (2.618033989221521810752093192…)

pos(24157817/39088169) = 464421339906882 (2.618033969017113072183685603…)

pos(39088169/63245986) = 1215870841639593 (2.618033964338027806153843993…)

[…]

In other words, pos(fibfrac(i+1)) / pos(fibfrac(i)) → φ^2 = 2.61803398874989484820458683… = φ + 1

Previously Pre-Posted (Please Peruse)