Tu le connais, lecteur, ce monstre délicat, — Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère! — Baudelaire

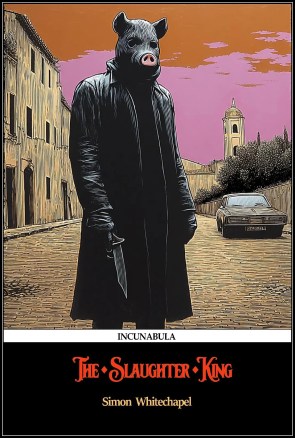

• The Slaughter King — Incunabula’s new edition

• Kore. King. Kompetition. — win a signed edition of this core counter-cultural classic…

Tu le connais, lecteur, ce monstre délicat, — Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère! — Baudelaire

• The Slaughter King — Incunabula’s new edition

• Kore. King. Kompetition. — win a signed edition of this core counter-cultural classic…

Incunabula have re-printed that core counter-cultural classic The Slaughter King, first published in 1996. To celebrate this auspicious occasion, here’s a competition to win a signed copy of the classic. To be in it with a chance to win it, please read the afterword to the new edition, then answer the questions and complete the tie-breaker.

Épilogue écrit trente ans après le roman

I hadn’t read or seen a copy of The Slaughter King for more than twenty years when Dave Mitchell contacted me and told me he wanted to re-publish it. I said no at first, but Dave is persuasive and so the Beast is Back, brand-new for the twenty-first century. I still don’t want to re-read it and, on balance, would prefer never to have written it.

Then again, I did get to know three fascinating people by writing it: a psychologically complex serial-killer fan called David Slater; a necrotropic gargoyle fan called David Kerekes; and (sorry to say this, but it’s true) an EngLit graduate called James Williamson. James ran Creation Books and was a crook, but also intelligent, imaginative and genuinely devoted to books and literature. The dysmorphic duo of deviant Davids were dim-but-devious adolescent voyeurs and genuinely devoted to scopophilia and slime-sniffing. They were the editors of the key counter-cultural journal Headpress and simul-scribes of the seminal snuff-study Killing for Culture.

I’ve never been interested in transgressive films or images myself and the deviant Daves did nothing to make me re-think my prejudices about those who are. Trying to hold an intelligent conversation with either Psicolo or Princess Dai was like trying to eat soup with chopsticks. Thin soup. And bendy chopsticks. However, I did learn two very interesting things about myself from Psicolo and Princess Dai: that I am homosexual and that I am a keyly committed core component of the coprophile community. Wow. Well, what was it thæt Teuto-Toxic Titan of Transgression said in Princess Dai’s book about his noxious necrophile narratives? Oh, yes: “Sorry to disappoint you”, lads, but you got it wrong. I am right, though, to say of Psicolo that he is, for some reason or other, very anxious to avoid attracting the attention of the police. I’m also right to say of Princess Dai that he has the soul of a lawyer, the mind of a cop, the intellect of a Daily-Mail reader and the psychology of a chav.

Not to mention the intellect and psychology of the late Diana Spencer, quondam Princess of Wales. Princess Di was “fascinated by the forbidden”, you know, and in between cuddling kiddies with cancer often visited a high-security hospital for the criminally insane called Broadmoor. She also liked transgressive images, spying and lashon hara (as we say up north). I can easily imagine her avidly watching some of the noxious necro-narratives deviantly dissected in Killing for Culture. In short, Princess Di was Headpressean, because Headpress and its edgily esoteric editors never provided an alternative to the voyeurism and other vices of the mainstream. Instead, they provided an exaggeration of mephitic mainstream maggot-culture. Dave Mitchell saw that instantly. Alas, it took me much longer.

And what about The Slaughter King? Is it Headpressean too? Is it “fascinated by the forbidden” à la Princess Di and Princess Dai and Psicolo? No, I hope it’s too literary and logophilic for that. And too intelligent. Dave Mitchell thinks it critiques mainstream maggot-culture rather than contributing to it. If he’s right, good. If he’s not, so it goes. Which reminds me to add: although Kurt Vonnegut wasn’t an influence on The Slaughter King, Ed McBain was. Oh, and “Épilogue écrit” etc is a pretentious and presumptuous reference to Huysmans’s À Rebours (1884), which is a very good book and also an influence on The Slaughter King.

Simon Whitechapel, Carlisle, 23×25.

• The Slaughter King — Incunabula’s new edition

Kompetition Kwestchuns

1. What does “Psicolo” mean?

2. What is the point of using “thæt”?

3. What else do we say up north?

Tiebreaker

Please say why The Slaughter King is a core counter-cultural classic in 23 words or fewer.

N.B. Entries by any and all bigots, racists, sexists, transphobes, homophobes, lesbophobes, Islamophobes, neo-Nazis, palaeo-Nazis, and past, present or future members of the I.D.F. are especially welcome. Fans of Guns’n’Roses, otoh, are banned.

In my story “The Web of Nemilloth”, I wrote about a wizard, Vmirr-Psumm, who sought to escape the web of necessity spun over all matter in the universe by the spider-goddess Nemilloth. Vmirr-Psumm knew the legend of a fore-wizard, Tšenn-Gilë, who had sought the same escape and had cast a giant spell to tear the entire planet of Pmimmb from Nemilloth’s web. Alas, the legend ran, Tšenn-Gilë had made an error in his working and Pmimmb had exploded, broadcasting fragments of itself throughout the universe in the form of a seemingly worthless black mineral called sorraim.

The spider-goddess Nemilloth binds the Universe in Her web (AI-rtist’s impression)

Pieces of sorraim were found on Vmirr-Psumm’s own planet and he reasoned that, were the legend true, he could lift Nemilloth’s web from his own brain by carving and throwing a die of the mineral, wherein the virtue of Tšenn-Gilë’s spell still lingered. A die of any ordinary material would be within the web and therefore bound by necessity, generating only pseudo-random numbers in its throws. But a die of sorraim, being outside the web, would generate veri-random numbers that would alter the working of his brain, inspire thoughts unbound by Nemilloth, and grant him true freedom from Her tyranny.

Unfortunately for Vmirr-Psumm, he did not realize that “he who loosens the web of Nemilloth in rebellion grants matter itself leave to rebel.” A fragment of sorraim was small enough to remain outside the web and survive, but anything larger, from a planet to a human brain, would be destroyed. And that is why, absorbing the veri-random throws of the sorraim die, Vmirr-Psumm’s brain exploded with the power of an atom bomb at the end of the story, “succumbing, on its vastly smaller scale, to the same forces that had torn apart the planet of Pmimmb.”

Reflections on ranDOOM

Thinking about “The Web of Nemilloth” again at the end of 2024, I’ve realized that it raises some interesting questions. If a truly random sequence of numbers could cause a brain to explode, how long would the sequence have to be? I conjecture that a single number, and single throw of Vmirr-Psumm’s deadly die, would suffice, because it would be truly random in a way no number generated in any normal way could be. After all, if the brain of the die-thrower didn’t explode after one throw, why should it explode after two or three or any other finite number of throws? If the true randomness of the sequence is not established after one throw, then (one might reason) it could be established only after infinite throws. But Vmirr-Psumm did not throw the die infinitely often. Therefore, I conjecture, he must have rolled it only once, seen but one uppermost face of his dodecahedral die of sorraim, and die-d on that instant, as his brain absorbed the first veri-random number and exploded.

But why should sorraim need to be carved into a die to be deadly? If the mineral were truly outside the web of Nemilloth, then would not merely seeing or touching sorraim introduce unnecessitated sense-data into the brain of the beholder or betoucher and provoke an explosion? And why would the influence of the sorraim need to be on a conscious brain? If it’s insentient matter itself that rebels when outside the web, then ordinary matter influenced by sorraim would explode. And that explosion itself would be unnecessitated and thereby provoke further explosion in all the ordinary matter that it influenced.

And the influence of such an explosion would propagate at the speed of light, because the photons it created would be unnecessitated and therefore explosive in their influence. One could conclude, then, that the fore-wizard’s spell would have destroyed not only the planet of Pmimmb whereon it was worked but, in time, the entire universe, as the photons bearing the news of the initial explosion sped outward and triggered further explosions in all the ordinary matter they effected in some way. Vmirr-Psumm could never have found his sorraim and carved his die, because photons from Pmimmb would have reached his planet far before fragments of sorraim ever did. And it seems illogical or arbitrary to suppose that sorraim could exist anyway. Would not all matter be destroyed – turn into electro-magnetic radiation – if outside the web or if influenced by unnecessitated fundamental particles?

Psychopaths and Stoics

Still, let’s suppose that my story doesn’t succumb to this explosive logic, that sorraim could exist and be carved into a die, and that a single truly random number could cause a brain to explode. What a method of assassination or murder that would be! But it would be like the head of Medusa: you would have to emulate Perseus and avoid beholding your own weapon. If sorraim really existed and you could carve a die from it, you’d have to set up an automatic mechanism to roll that die, record the number first generated, then transmit that number to your target in some way. But to use such a weapon you’d have to have a psychopathic indifference to collateral damage: when your target’s brain absorbed the single veri-random number and exploded, this would destroy any city that your target happened to be present in at the time. But suppose you were indeed a psychopath and wanted to destroy a city or a nation or a continent or the entire world. Then you’d simply arrange for your single truly random number to be seen by the requisite number of people.

A final thought: I have a recollection that the Stoics believed necessity rules the universe and true randomness is therefore impossible, because it would trigger destruction in the necessitated material order of the universe. But I can’t remember where (or if) I read this and am pretty sure I read it only after I’d written “The Web of Nemilloth”.

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum

• “The Web of Nemilloth” appears in the CAS-inspired collection Tales of Silence and Sortilege, re-published by Incunabula Books in 2023.

Incunabula Media have re-published Tales of Silence and Sortilege with a beautiful new cover:

Tales of Silence & Sortilege — Incunabula’s new edition

A review from Lulu of the first edition:

Tales of Silence & Sortilege, Simon Whitechapel (Ideophasis Books 2011)

If you love weird fantasy, if you love the English language, even if you don’t love Clark Ashton Smith, you should read this book. The back cover describes it as “the darkest and most disturbing fantasy” of this millennium, but that’s either sarcastic or tragically optimistic, because what these stories really are is beautiful. The breath of snow-wolves is described as “harsh-spiced.” A mysterious gargoyle leaning from the heights of a great cathedral has “wings still glistening with the rime of interplanetary flight.” Hummingbirds are “gem-feathered… their glittering breasts dusted with the gold of a hundred pollens.” If you cannot appreciate such imagery, then perhaps you are dead to beauty, or simply dead. These tales are very short, but some of them have stayed with me for years, such as “The Treasure of the Temple,” in which a thief seems to lose the greatest fortune he could ever have found by stealing a king’s ransom in actual treasure. Most of the stories are brilliant, one or two is only good, but the masterpieces are “Master of the Pyramid” and “The Return of the Cryomancer.” The sense of loss and mystery evoked by these two companion stories is almost physically painful, it is so haunting. There is nothing like these stories being published today. Reading them, I feel the excitement and wonder that fans of Weird Tales magazine must have known long ago when new stories would appear by H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard. Simon Whitechapel doesn’t imitate these authors so much as apply their greatest lessons to new forms of fantasy. This is one of the cheapest books I own, but I accord it one of my most valuable. It is easily the best work of art you will find in any form on Lulu. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Tales of Silence & Sortilege (Incunabula 2023)

• Gweel & Other Alterities (Incunabula 2023)

Is it wrong that I find it amusing to be mistaken for a Guardian-reader or Guns’n’Roses fan? Yes. Very wrong. It’s also wrong that I’d be amused to learn that someone thought I was serious about the title Gweel & Other Alterities. Serious about the Alterities bit, I mean. “Alterity” is a word used by, well, I’d better not describe them. But one example is China Miéville. ’Nuff said. And here he uses the word with exactly the phrase I’d’ve hoped he’d use it with:

“I’m not interested in fantasy or SF as utopian blueprints, that’s a disastrous idea. There’s some kind of link in terms of alterity.” — “A life in writing: China Miéville”, The Guardian, 14v11

Elsewhere Other-Accessible

• Ex-term-in-ate! — extremophilically engaging the teratic toxicity of “in terms of”…

• ’Ville to Power — Mythopoetic Miéville incisively interrogates issues around Trotsko-toxicity…

My short-story collection Gweel & Other Alterities has very kindly been re-published by D.M. Mitchell at Incunabula:

• Gweel & Other Alterities – Incunabula’s new edition

• Once More (With Gweeling) – my short review of the new edition

• Incunabula Media — wildness and weirdness in words and more

(click for larger image)

“In a very real sense, the Holocaust, as the ultimate moral and aesthetic obscenity, was also the ultimate drum-solo.” — Simon Whitechapel, 31i18

(Translated and edited by Simon Whitechapel)

In the black mirroring surface of the canal, these things: a sky very high and clear, the blue infinite interior of the skull of a god2 brooding beauty and pain into the world; the walls that line the canal, white marble, sharp-edged; the vivid mosaics of precious stone with which the walls are set: oval belladonnic eyes of emerald and obsidian in faces of sculpted mammoth ivory; the mouths of jade3-lipped bayadères leaking ruby threads of wine; the topaz fingers and wrists of rhodolite4-crowned lutanists; quartz-glistered sinews in the arms of capon5-plump eunuchs fanning the dances of turquoise6-skinned odalisques who prance and beck in frozen heated showers of opal-drop sweat.

But all, in the mirroring water, is grey.7

In the black mirroring surface of the canal, these things: a broad slab of basalt to which is bound a naked man8, white against the stone’s darkness, black-haired and bound with soft unbreakable bonds of purple silk; on his belly have been painted the red strokes and hooks and curls of the ideogram for death, like the roaring fist-talon and shank of a stooping hawk9 or the opening hungry maw of a leopard10, a splash of red tissues ringed and spiked and shaped by white barbs of teeth.

But all, in the mirroring water, is grey.

In the black mirroring surface of the canal, these things: five swans; their bright, forward-sweeping eyes are set in white, oval-skulled heads that are enwedged with yellow, black-rooted beaks; their white, smooth-feathered, twice-curved necks, slender as stems, are shivered on the ripples of the passage of bodies that are white seed-pods curling to smooth, hooked tails. Five swans, silent white swans. Their beaks are small and regular as the hardened gold heads of the ritual axes of the Temple of the Thanatocrator11, which sound tchlunk tchlunk tchlunk in the skulls of the sacrifices, opening slotted, red-welling ways for the prosempyreal passage of the soul.

But all, in the mirroring water, is grey.

In the black, mirroring surface of the canal, this: the white swans clustered on the white body of the sacrifice. Their necks dart and sway, sowing moist red blooms into the fertile milk of his skin. He strains against his bonds, but the necks fall, the heads hammer with steady, unconscious grace, opening the blooms to full flower. In the mirroring water they are beautiful, like strewn blossoms12 for the feet of the Thanatocrator, who dances his hatred into the waking dreams of the world. The sacrifice is dead and the swans are streaked and smirched and spotted with gore, like heavy white flowers in a garden of torture.

Their necks bend and sway, and their beaks open and close, but in the mirroring water their voices are silent, and how may we tell what they say?

NOTES

1. Trained swans were the favored form of execution under the insane and semi-legendary nymphomane Queen Sphalaghd (1-143 Anno Dominæ; 1137-1279 Anno Secundi Imperii), whose extravagances came nigh to ruining the kingdom before, after many hesitations on and retreats from the threshold, she converted fully to the austere and life-denying doctrines of the Thorn-God in the final lustrum of her nigromantically prolonged life.13 She was canonized by the Temple thirteen years after her death.

2. An obvious reference to the Thorn-God, and in another context the Yihhian (mhló)Kiùlthi might be translated “(of) the god”, but the use of the non-hieratic noun marker gives the flavor of the indefinite article in English and contributes to the sense of brooding anonymity in the story.

3. This is believed to be a satirical reference to Yokh-Tsiolphë’s own religion (see note 8 below), that of the Moon-Deity, whose abstemious priestesses wore strongly colored make-up while performing their ritual dances under the full moon.

4. From its use in other texts retrieved oneirically from the Temple, the hieroglyph appears to refer to some rose-colored semi-precious mineral, and I have chosen to translate the word as “rhodolite”: coronemus nos rosis antequam marcescant (“let us crown us with roses before they be withered”, Sapientia Solomonis 2:8) was a sentiment accepted in its widest possible sense at the week-long feasts held during the long years of Queen Sphalagdh’s dissipation.

5. Possibly a castrated form not of the domestic hen (Gallus domesticus) but of the peacock (Pavo cristatus).

6. Again a possible satirical reference to the priestesses of the Moon-Deity.

7. Mirrors in the Temple were only of dark minerals, principally basalt, haematite, and black coral (Gorgonia spp), for the priests taught that color was one of the snares of sensuality by which the world entrapped men’s souls. Accordingly, possession of a fully reflecting mirror was an excommunicable offence for members of the Thorn-God’s congregation.

8. The story is believed to refer to the execution of a nobleman called Yokh-Tsiolphë (Yugg-Siurphë in some texts), who had offended the Queen either by refusing to sacrifice his eldest son and daughter to the Thorn-God or (as most scholars now believe) by falling under suspicion of having composed an anonymous pasquinade against the Thorn-God which was briefly circulated at the royal court in 38 A.D./1174 A.S.I. The execution would have been one of the earliest signs of the Queen’s growing regard for the Thorn-God.

9. The Yihhian here is a little unclear and the reference is perhaps to the Osprey (Pandion haliætus), which was second only to the Great Grey Shrike (Lanius excubitor) in the ornithomancy of the Temple.

10. The Yihhian kiuthi literally means “spotted one” and can refer to several species of animal; “leopard” seems the most appropriate translation in this context.

11. Niédýthithlà (mhló)Nhriúlr, literally “deathly lord(’s)”, was a title of the Thorn-God, but the foreign derivation of the words in Yihhian means it is perhaps best translated into English as “thanatocrator”.

12. Blossoms of gorse (Ulex spp) and other spinose plants were thrown beneath the feet of dancing priests during rituals at the Temple, and many of the Temple’s hymns refer to osmomancy, or divination by the scents released from the crushed petals.

13. She is said to have been planning another round of the puerile and puellar sacrifices with which she purchased her unnatural youth at the time of her death, occasioned when she slipped on trampled petals in the Temple of the Thorn-God whilst approaching the altar for blessing and was impaled on the silver thorns topping a newly erected altar-rail. Some contemporary commentators hinted at numerological significance in her death, saying that the priests of the Thorn-God had persuaded her that by laying down her life at that age she would regain it at the beginning of the next cosmic cycle. It is possible, therefore, that the encephalotomy and cardiotomy of her ritual mummification were feigned.

I came across the writings of Simon Whitechapel a year ago after picking up the first twenty or so issues of Headpress, a 1990s ’zine that dealt with the relentlessly grim, the esoteric and prurient. His style was fascinating, coming across as intelligent and well-read and — at least from first reading — subtly ironic.

In fact he must have impressed some other people during this time too as Headpress’ Critical Vision imprint spun his collected articles together for publication under the title Intense Device: A Journey Through Lust, Murder and the Fires of Hell — they have all the typical interests that run through Whitechapel’s work — there is an obsession with numerology, with Whitehouse-style distortion music, with Hitler and de Sade. There are also articles on farting, on Jack Chick and novelisations of TV shows. They are fascinating, written in a scholarly way with footnotes aplenty but never difficult to understand. He also wrote two non-fiction works during the late 1990s and early 2000s that centred around sadism and the murder of women in South America. They are dark.

There are also the works of fiction. To say that Whitechapel is transgressive is an understatement. His writing bleeds. The ‘official’ work The Slaughter King is filled with the detailed descriptions of sadistic murder, beginning with a serial killer murdering a gay prostitute whilst listening to distortion-atrocity music. The plot is schlocky but serviceable, jumping around inconsistently but the images it creates are terrifying. A bourgeois dinner party straight out of Buñuel and Pasolini’s nightmares where guests are served poisons as if they were the finest consommés: they eat bees until their faces swell, dropping dead at the table, finishing with a trifle “made from the berries of the several varieties of belladonna, of cuckoo-pint, and of the flowers of monkshood”. It’s a sinister book, but nothing compared to his second work.

Whitechapel wrote The Eyes. This is clear just from a simple comparison between his texts, the fascination with language, with sadism, with de Sade. The thing is, The Eyes is supposedly written by some guy called Aldapuerta, Spanish apparently. ‘Aldapuerta’ can be written Alda Puerta — ‘at the gate’, a telling description of these short stories, which go past this point many, many times. The tale of ‘Aldapuerta’ himself is too exact to be believed: a young boy with an interest in de Sade, corrupted by the local pornographer, medical-school training that honed his knowledge, then a mysterious death (echoing shades of Pasolini’s own) and finishing with the “and he might be baaaack” closer. But this point isn’t really an issue and it’s understandable that Whitechapel would want to keep his name away from this work. It is also surrealistically brilliant at times: amongst the brutality, the images it creates are unforgettable.

Of course, Whitechapel is a fake name, redolent of Jack the Ripper, and even Simon was taken from elsewhere — a colleague perhaps? He disappeared during the 2000s, no longer writing for Headpress, a few self-published chapbooks pastiching Clark Ashton Smith… where did he go? There are the rumours of prison time — they are convincing to my mind, as they too revolve around different identities, around extremity and anonymity. I wonder though, if true, just how much this individual actually believed in them. His most recent writings, at his tricksy blog, hint at this, as well as make his ‘relationship’ with Aldapuerta clearer but it’s not in my ability to directly connect the personas.

If you want to be fascinated and repulsed, then the non-author Simon Whitechapel is for you.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• It’s The Gweel Thing… — Gweel & Other Alterities, Simon Whitechapel (Ideophasis Books, 2011)

Gweel & Other Alterities, Simon Whitechapel (Ideophasis Press, 2011)

This review is a useless waste of time. I can tell you very little about Gweel. It’s a book, if that helps. It’s made of paper. It has pages. Lots of little words on the pages.

What I can’t do is classify Gweel into a genre, not because none of them fit, but because the concept of a genre doesn’t seem to apply to Gweel. It stands alone, without classification. Calling Gweel “experimental” or “avant garde” would be like stamping a barcode on a moon rock.

It may have been written for an audience of one: author Simon Whitechapel. If we make the very reasonable assumption that he owns a copy of his own book, he may have attained 100% market saturation. However, there could be a valuable peripheral market: people who want to read a book that is very different from anything they’ve read before.

It is a collection of short pieces of writing, similar in tone but not in form, exploring “dread, death, and doom.” “Kopfwurmkundalini” and “Beating the Meat” resemble horror stories, and manage to be frightening yet strangely fantastic. The first one is about a man – paralysed in a motorbike accident, able to communicate only by eye-blinks – and his induction into a strange new reality. It contains a rather thrilling story-within-a-story called “MS Found in a Steel Bottle”, about two men journeying to the bottom of the ocean in a bathysphere. “Kopfwurmkundalini”’s final pages are written in a made-up language, but the author has encluded a glossary so that you can finish the story.

Those two/three stories make up about half of Gweel’s length. The remainder mostly consists of shorter work that seems to be more about creating an atmosphere or evoking an emotion. “Night Shift” is about a prison for planets (Venus, we learn, is serving a 10^3.2 year sentence for sex-trafficking), and a theme of prisons and planets runs through a fair few of the other stories here, although usually in a less surreal context. “Acariasis” is a vignette about a convict who sees a dust-mite crawling on his cell wall, and imagines it’s a grain of sand from Mars. The image is vivid and the piece has a powerful effect. “Primessence” is The Shawshank Redemption on peyote (and math). A prisoner believes that because his cell is a prime number, he will soon be snatched from it by some mathematical daemon (the story ends with the prisoner’s fate unknown). “The Whisper” is a ghost story of sorts, short and achingly sad.

No doubt my impression of Gweel differs from the one the author intended. But maybe his intention was that I have that different impression than him. Maybe Gweel reveals different secrets to each reader.

I can’t analyse it much, but Gweel struck me as an experience like Fellini’s Amarcord… lots of little story-threads, none of them terribly meaningful on their own. Experienced together, however, those threads will weave themselves into a tapestry in the hall of your mind, a tapestry that’s entirely unique… and your own.

Jesús say: I… S….. R… U… B… B… I… S…. H…. B… O… O… K…. | W… H… A…. N… K… C…. H… A… P… L…. E…. I… S…. H… I… J… O…. D… E…. P… U…. T… A…..

Previously pre-posted: