Medieval music by Vox Vulgaris and Trouvère

At one time, people could never hear their own voices the way others heard them, because our own voices come to us partly through the flesh and bone of our skulls. Then phonographs and tape-recorders were invented and nowadays we all know what we really sound like. But what does the medieval music of groups like Vox Vulgaris and Trouvere really sound like? It comes to us through the flesh and bone of history and we listen to it with uninnocent ears, soaked in a hundred different genres. Medieval music doesn’t stand alone any more, it stands in contrast: acoustic, not amplified; simple, not complex; authentic, not artificial.

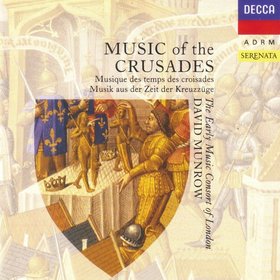

Or is it authentic? No, because it’s not the music that comes most readily to hand or to ear any more. Playing it and listening to it are roles you choose, not roles you’re born into, because it’s part of a cultic fringe nowadays. Ferns once ruled the forests; now they’re pushed to the damp or rocky margins by more advanced plants. So this is ferny music: fresh, green and simple, with a glamour of exile and overthrow. You can hear that glamour more strongly in Trouvere, who play slow, sad and sometimes stately music that seems both to celebrate and to lament the Middle Ages. Vox Vulgaris, which literally means “Popular Voice”, celebrate and don’t lament: they’re raucous and almost rocking and sound like a group for inns and peasants’ weddings, not for courts and cathedrals. They’re fun, not bittersweet like Trouvere, who remind me of the Early Music Consort of London. But, like Vox Vulgaris, Trouvere play instrumentals and don’t add lost languages to their lost music.

The music is enough, but they’re surely playing it with a modern accent that would raise smiles or laughter in a real medieval audience. We can’t go back and that is part of why their music is so attractive. It lilts, it longs and it laments, searching for something it will never find. And that is another way Trouvere evoke the Middle Ages:

La royne Blanche comme ung lys,

Qui chantoit à voix de sereine;

Berthe au grand pied, Bietris, Allys;

Harembourges, qui tint le Mayne,

Et Jehanne, la bonne Lorraine,

Qu’Anglois bruslèrent à Rouen;

Où sont-ilz, Vierge souveraine?…

Mais où sont les neiges d’antan!

“Ballade des dames du temps jadis”, François Villon (1431-c.1485)

White Queen Blanche, like a queen of lilies,

With a voice like any mermaiden,—

Bertha Broadfoot, Beatrice, Alice,

And Ermengarde the lady of Maine,—

And that good Joan whom Englishmen

At Rouen doomed and burned her there,—

Mother of God, where are they then?…

But where are the snows of yester−year.

Translation by Rossetti.