• They were going over a passage that, in Joyce’s opinion, was “still not obscure enough”, and inserting Samoyed words into it. — Gordon Bowker, James Joyce: A Biography (2012), pp. 448-9.

Tag Archives: modernism

Jewels in the Skull

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

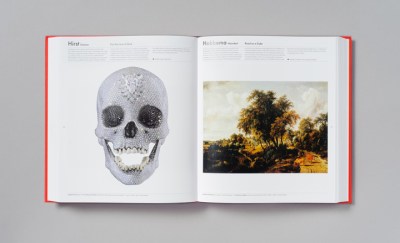

An A to Z of artists, mostly painters, occasionally sculptors, installers and performers, with a few photographers and video-makers too. You can trace the development, culmination and corruption of high art all the way from Giotto and Fra Angelico through Van Eyck and Caravaggio to Auerbach and Twombly. But the modernist dreck heightens the power of the pre-modernist delights. A few pages after Pieter Claesz’s remarkable A Vanitas Still Life of 1645 there’s Joseph Cornell’s “Untitled” of 1950. One is a skull, watch and overturned glass, skilfully lit, minutely detailed, richly symbolic; the other is a wooden box containing a “frugal assortment of stamps, newspaper cuttings and other objects with no particular relevance to each other”. From the sublime to the slapdash. Over the page from Eleazar Lissitzky’s Composition of 1941 there’s Stefan Lochner’s The Virgin and Child in a Rose Arbour of 1442. One is like a child’s doodle, the other like a jewel. From the slapdash to the sublime.

And so it goes on throughout the book, with beautiful art by great artists following or preceding ugly art by poseurs and charlatans. But some of the modern art is attractive or interesting, like Bridget Riley’s eye-alive Cataract 3 (1961) and Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God (2006). Riley and Hirst aren’t great and Hirst at least is more like an entrepreneur than an artist, but their art here is something that rewards the eye. So is Riley’s art elsewhere, as newcomers to her work might guess from the single example here. That is one of the purposes of a guide like this: to invite – or discourage – further investigation. I vaguely remember seeing the beautiful still-life of a boiled lobster, drinking horn and peeled lemon on page 283 before, but I wouldn’t have recognized the name of the Dutch artist: Willem Kalf (1619-93).

Willem Kalf, Still Life (c. 1653)

Elsewhere, I was surprised and pleased to see an old favourite: John Atkinson Grimshaw and his Nightfall on the Thames (1880). Many more people know Grimshaw’s atmospheric and eerie art than know his name, because it often appears on book-covers and as illustrations. If Phaidon are including him in popular guides with giants like Da Vinci, Dürer, Raphael and Titian, perhaps he’ll return to his previous fame. I certainly hope so.

Finding Grimshaw here made a good guide even better. The short texts above each art-work pack in a surprising amount of information and anecdote too. What you learn from the texts raises some interesting questions. For example: Why has one small nation contributed so much to the world’s treasury of art? From Van Eyck to Van Gogh by way of Hieronymus Bosch and Jan Vermeer, Holland is comparable to Italy in its importance. But only in painting, not sculpture or architecture. There aren’t just patterns of pigment, texture and geometry in this book: there are patterns of DNA, culture and evolution too. Brilliant, beautiful and banal; skilful, subtle and slapdash: The Art Book has all that and more. It puts jewels inside your skull.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• Ai Wei to Hell — How to Read Contemporary Art, Michael Wilson

• Eyck’s Eyes — Van Eyck, Simone Ferrari

• Face Paint — A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, Laura Cumming

Words at War

Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology, ed. Tim Kendall (Oxford University Press 2013)

Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology, ed. Tim Kendall (Oxford University Press 2013)

J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis are famous names today, but both might have died young in the First World War. If so, they would now be long forgotten. Generally speaking, novelists, essayists and scholars take time to mature and need time to create. Poets are different: they can create something of permanent value in a few minutes. This helps explain why nearly half the men chosen for this book did not reach their thirties:

• Rupert Brooke (1887-1915)

• Julian Grenfell (1888-1915)

• Charles Sorley (1895-1915)

• Patrick Shaw Stewart (1888-1917)

• Arthur Graeme West (1891-1917)

• Isaac Rosenberg (1890-1918)

• Wilfred Owen (1893-1918)

And none of them left substantial bodies of work. Indeed, “except for some schoolboy verse”, Patrick Shaw Stewart is known for only one poem, which “was found written on the back flyleaf of his copy of A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad after his death” (pg. 116). It begins like this:

I saw a man this morning

Who did not wish to die:

I ask and cannot answer,

If otherwise wish I.

(From I saw a man this morning)

Housman is here too, with Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries, which Kipling, also here, is said to have called “the finest poem of the First World War” (pg. 14). I don’t agree and I would prefer less Kipling and no Thomas Hardy. That would have left space for something I wish had been included: translations from French and German. The First World War was fought by speakers of Europe’s three major languages and this book makes me realize that I know nothing about war poetry in French and German.

It would be interesting to compare it with the poetry in English. Were traditional forms mingling with modernism in the same way? I assume so. Wilfred Owen looked back to Keats and the assonance of Anglo-Saxon verse:

Our brains ache, in the merciless iced winds that knive us…

Wearied we keep awake because the night is silent…

Low, drooping flares confuse our memory of the salient…

Worried by silence, sentries whisper, curious, nervous,

But nothing happens. (Exposure)

David Jones (1895-1974) looked forward:

You can hear the silence of it:

You can hear the rat of no-man’s-land

rut-out intricacies,

weasel-out his patient workings,

scrut, scrut, sscrut,

harrow-out earthly, trowel his cunning paw;

redeem the time of our uncharity, to sap his own amphibi-

ous paradise.

You can hear his carrying-parties rustle our corruptions

through the night-weeds – contest the choicest morsels in his

tiny conduits, bead-eyed feast on us; by a rule of his nature,

at night-feast on the broken of us. (In Parenthesis)

But is there Gerard Manley Hopkins in that? And in fact In Parenthesis was begun “in 1927 or 1928” and published in 1937. T.S. Eliot called it “a work of genius” (pg. 200). I’d prefer to disagree, but I can’t: you can feel the power in the extract given here. Isaac Rosenberg had a briefer life and left briefer work, but was someone else who could work magic with words:

A worm fed on the heart of Corinth,

Babylon and Rome.

Not Paris raped tall Helen,

But this incestuous worm

Who lured her vivid beauty

To his amorphous sleep.

England! famous as Helen

Is thy betrothal sung.

To him the shadowless,

More amorous than Solomon.

A beautiful poem about an ugly thing: death. A mysterious poem too. And a sardonic one. Rosenberg says much with little and I think he was a much better poet than the more famous Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves. They survived the war and wrote more during it, which helps explain their greater fame. But the flawed poetry of Graves was sometimes appropriate to its ugly theme:

To-day I found in Mametz Wood

A certain cure for lust of blood:Where, propped against a shattered trunk,

In a great mess of things unclean,

Sat a dead Boche; he scowled and stunk

With clothes and face a sodden green,

Big-bellied, spectacled, crop-haired,

Dribbling black blood from nose and beard.

A poem like that is a cure for romanticism, but that’s part of what makes Wilfred Owen a better and more interesting poet than Graves. Owen’s romanticism wasn’t cured: there’s conflict in his poems about conflict:

I saw his round mouth’s crimson deepen as it fell,

Like a sun, in his last deep hour;

Watched the magnificent recession of farewell,

Clouding, half gleam, half glower,

And a last splendour burn the heavens of his cheek.

And in his eyes

The cold stars lighting, very old and bleak,

In different skies.

But how good is Owen’s work? He was a Kurt Cobain of his day: good-looking, tormented and dying young. You can’t escape the knowledge of early death when you read the poetry of one or listen to the music of other. That interferes with objective appraisal. But the flaws in Owen’s poetry add to its power, increasing the sense of someone writing against time and struggling for greatness in a bad place. The First World War destroyed a lot of poets and perhaps helped destroy poetry too, raising questions about tradition that some answered with nihilism. As Owen asks in Futility:

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

—O what made fatuous sun-beams toil

To break earth’s sleep at all?

Some of the poets here were happy to go to war, but it wasn’t the Homeric adventure anticipated by Patrick Shaw Stewart. He learnt that high explosive is impersonal, bullets kill at great distance and machines don’t need rest. Poetry of the First World War is about a confrontation: between flesh and metal, brains and machinery. It’s an interesting anthology that deserves much more time than I have devoted to it. The notes aren’t intrusive, the biographies are brief but illuminating, and although Tim Kendall is a Professor of English Literature he has let his profession down by writing clear prose and eschewing jargon. He’s also included some “Music-Hall and Trench Songs” and they speak for the ordinary and sometimes illiterate soldier. The First World War may be the most important war in European history and this is a good introduction to some of the words it inspired.