“Descending Toward the Moon” (1951) by Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986)

“Descending Toward the Moon” (1951) by Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986)

• Et que signifie donc d’être chair ?

• Und was heißt es, Fleisch zu sein?

• E che vuol dire essere carne?

• ¿Y qué quiere decir ser carne?

• और देह होना आखिर क्या है?

• და რას ნიშნავს ხორცად ყოფნა?

• 而为肉身,究竟意味着什么?

• अथ मांसत्वं किमर्थम्?

• ⲁⲩⲱ ⲧⲓ ⲟⲩⲛ ⲡⲉ ⲡⲓⲥⲁⲣⲝ ⲉⲧⲙⲉ?

• 𒅇 𒍑𒆪 𒅆𒂟 𒅗?

Tu le connais, lecteur, ce monstre délicat, — Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère! — Baudelaire

• The Slaughter King — Incunabula’s new edition

• Kore. King. Kompetition. — win a signed edition of this core counter-cultural classic…

Y Rhosyn a’r Wylan

There’s a rose at Number Seven,

Tho’ the air is wintered now,

And it glows at Number Seven,

In the brain behind thy brow.

There’s a gull that turns the stillness

Of the air above thy head:

’Tis the gull that spurns the illness

Of the creed where color’s dead.

There’s a rose at Number Seven;

There’s a gull that turns the air:

And what glows at Number Seven

Is the spurner turning there.

Odoric (also known as Odoryc, Odorous, Dendric, Dryadic, Floric, and Floral) will be a language of odors used by many races of intelligent tree and a few races of intelligent flower for an indefinite period between 15,000,000 and 20,000,000 years in the future. In its standard form among trees it will be based on odors released from special odorifera (scent-organs) on leaves or branches and wafted from tree to tree by the wind or air-diffusion. Because of the chemical nature of Odoric, a simple exchange of greetings will take several hours in favorable weather, a brief conversation several days, and the recitation of an average tree-saga a year or more.

Odoric will have innumerable and often mutually unintelligible dialects falling into three main families: Coniferous Odoric, as used by conifers; Deciduous Odoric, as used by non-coniferous deciduous trees; and Floral Odoric, as used by flowers. Its native written form will evolve late and be based on chemical markers laid down within leaves and roots as a mnemonic for individual trees. In this form, it cannot be represented directly by a script suitable for human eyes, but Odoric will also be written by a non-plant species: an advanced race of intelligent squirrel that will discover and transcribe the language about 28,000,000 years in the future. This Sciurine (Squirrel) Odoric is presented here in one of its several forms.

As can be seen, the letters, or osmemes, of the script fall into six eight-letter scent-series named after the closest equivalent scent in the present-day plant kingdom. The letters of each series will be distinguished in their wafted (that is, “spoken”) form by subtle chemical variations, although some may be created artificially to complete an incomplete series – eight will apparently have mystical significance for squirrels, perhaps under the influence of a mathematic mysticism among trees. For example, ![]() seems to be a homosme of

seems to be a homosme of ![]() , or to become so in some dialects of Odoric. Each letter is transcribed into Roman using the initial of the scent in the series to which it will belong, plus a subscripted digit indicating its place in the series: the second letter of the Jasmine series,

, or to become so in some dialects of Odoric. Each letter is transcribed into Roman using the initial of the scent in the series to which it will belong, plus a subscripted digit indicating its place in the series: the second letter of the Jasmine series, ![]() , is therefore J2 and the fifth letter of the Honeysuckle series,

, is therefore J2 and the fifth letter of the Honeysuckle series, ![]() , is H5.

, is H5.

There will be only two punctuation marks in this form of Sciurine Odoric: < ![]() >, used like a comma, semi-colon, or colon, and <

>, used like a comma, semi-colon, or colon, and < ![]() >, used like a full stop. It is believed that these marks will have no wafted form and will be used purely for the convenience of the squirrels transcribing a passage of Odoric.

>, used like a full stop. It is believed that these marks will have no wafted form and will be used purely for the convenience of the squirrels transcribing a passage of Odoric.

Transliteration

L3H1C5L6C6 J6H4J8C2C5S1 L2H7L7C6V8V5 L7C2S6C4L2H7 C6H8J5H3C6J6H4 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L3H1C5L6C6V2, H3C6J6H4J8C2 H4J8C2C5S1J1V5J4 L2H7L7C6V8V5 L7C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L2H7L7C6V8V5 C2L3H1C5L6C6V2V7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L3H1C5L6C6V2, H7L7C6V8V5C5 L7C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L2L7C2H8C6V7S6 L2L7C2H8C6 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L3H1C5L6C6V2, S1J1V5J4L7C2 L7C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 C6V8V5C5C2L3H1C5 L3L2L7C2H8 C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2H8C6 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L3H1C5L6C6V2 C5C2L3H1C5L6 L7C2S6C4L2H7 C2L3H1C5L6C6V2 J4L7C2S6C4L2H7L7. C5S1J1V5J4 L3H1C5L6C6 L7C2S6C4L2H7 C2C5S1J1V5J4L7C2 L3H1C5L6C6V2, J6H4J8C2C5S1 L7C2S6C4L2H7 C2C5S1J1V5J4L7 L3H1C5L6C6V2, L2H7L7C6V8V5 H3C6J6H4J8C2 L7C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 J1V5J4L7C2S6 L3H1C5L6C6V2, L2L7C2H8C6V7S6 H7L7C6V8V5C5 L7C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 J8C2C5S1J1V5J4 L3H1C5L6C6V2, C5C2L3H1C5L6 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 S1J1V5J4L7C2 L7C2S6C4L2H7 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L2L7C2H8C6V7 L2L7C2H8C6 L7C2S6C4L2H7L7C6 L3H1C5L6C6V2 L7C2H8C6V7S6L6 L7C2S6C4L2H7 C2L3H1C5L6C6V2 J4L7C2S6C4L2H7L7.

Literal translation

sun rain with thou bless plural subj, leaf branch with thou plural wind stifle plural subj, root thou plural earth eat plural subj, seed thou plural number adj not be plural subj true thou stand future. but sun thou scorch subj, rain thou drown subj, wind leaf thou plural tear subj, earth root thou plural crush subj, worm plural seed thou plural each eat plural subj false thou stand future.

Idiomatic translation

“May the sun and rain bless thee, thy leaves and branches stifle the wind, thy roots swallow the (whole) earth, thy seeds be innumerable if thou art true. But may the sun scorch thee, the rain drown thee, the wind tear thy leaves, the earth crush thy roots, worms eat all thy seeds if thou art false.” – Traditional Odoric formula used to seal vows and treaties.

© 2005 Simon Whitechapel

A fern is a fractal, a shape that contains copies of itself at smaller and smaller scales. That is, part of a fern looks like the fern as a whole:

Fern as fractal (source)

Millions of years after Mother Nature, man got in on the fract, as it were:

The Sierpiński triangle, a 2d fractal

The Sierpiński triangle is a fractal created in two dimensions by a point jumping halfway towards one or another of the three vertices of a triangle. And here is a fractal created in one dimension by a point jumping halfway towards one or another of the two ends of a line:

A 1d fractal

In one dimension, the fractality of the fractal isn’t obvious. But you can try draggin’ out (or dragon out) the fractality of the fractal by ferning the wyrm, as it were. Suppose that after the point jumps halfway towards one or another of the two points, it’s rotated by some angle around the midpoint of the two original points. When you do that, the fractal becomes more and more obvious. In fact, it becomes what’s called a dragon curve (in Old English, “dragon” was wyrm or worm):

Fractal with angle = 5°

Fractal 10°

Fractal 15°

Fractal 20°

Fractal 25°

Fractal 30°

Fractal 35°

Fractal 40°

Fractal 45°

Fractal 50°

Fractal 55°

Fractal 60°

Fractal 0° to 60° (animated at ezGif)

But as the angle gets bigger, an interesting aesthetic question arises. When is the ferned wyrm, the dragon curve, at its most attractive? I’d say it’s when angle ≈ 55°:

Fractal 50°

Fractal 51°

Fractal 52°

Fractal 53°

Fractal 54°

Fractal 55°

Fractal 56°

Fractal 57°

Fractal 58°

Fractal 59°

Fractal 60°

Fractal 50° to 60° (animated)

At angle >= 57°, I think the dragon curve starts to look like some species of bristleworm, which are interesting but unattractive marine worms:

A bristleworm, Nereis virens (see polychaete at Wikipedia)

Finally, here’s what the ferned wyrm looks like in black-and-white and when it’s rotating:

Fractal 0° to 60° (b&w, animated)

Fractal 56° (rotating)

Fractal 56° (b&w, rotating)

Double fractal 56° (b&w, rotating)

Previously Pre-Posted (Please Peruse)…

• Curvous Energy — a first look at dragon curves

• Back to Drac’ — another look at dragon curves

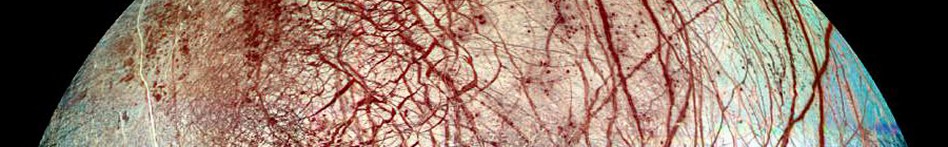

Atom bombs exploding on New York by the astro-artist Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986)

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

The fact is, we none of us enough appreciate the nobleness and sacredness of color. Nothing is more common than to hear it spoken of as a subordinate beauty, — nay, even as the mere source of a sensual pleasure; and we might almost believe that we were daily among men who

“Could strip, for aught the prospect yields

To them, their verdure from the fields;

And take the radiance from the clouds

With which the sun his setting shrouds.”

But it is not so. Such expressions are used for the most part in thoughtlessness; and if the speakers would only take the pains to imagine what the world and their own existence would become, if the blue were taken from the sky, and the gold from the sunshine, and the verdure from the leaves, and the crimson from the blood which is the life of man, the flush from the cheek, the darkness from the eye, the radiance from the hair, — if they could but see for an instant, white human creatures living in a white world, — they would soon feel what they owe to color. The fact is, that, of all God’s gifts to the sight of man, color is the holiest, the most divine, the most solemn. We speak rashly of gay color, and sad color, for color cannot at once be good and gay. All good color is in some degree pensive, the loveliest is melancholy, and the purest and most thoughtful minds are those which love color the most.

• John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol II, Chapter 5, xxx