The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

An A to Z of artists, mostly painters, occasionally sculptors, installers and performers, with a few photographers and video-makers too. You can trace the development, culmination and corruption of high art all the way from Giotto and Fra Angelico through Van Eyck and Caravaggio to Auerbach and Twombly. But the modernist dreck heightens the power of the pre-modernist delights. A few pages after Pieter Claesz’s remarkable A Vanitas Still Life of 1645 there’s Joseph Cornell’s “Untitled” of 1950. One is a skull, watch and overturned glass, skilfully lit, minutely detailed, richly symbolic; the other is a wooden box containing a “frugal assortment of stamps, newspaper cuttings and other objects with no particular relevance to each other”. From the sublime to the slapdash. Over the page from Eleazar Lissitzky’s Composition of 1941 there’s Stefan Lochner’s The Virgin and Child in a Rose Arbour of 1442. One is like a child’s doodle, the other like a jewel. From the slapdash to the sublime.

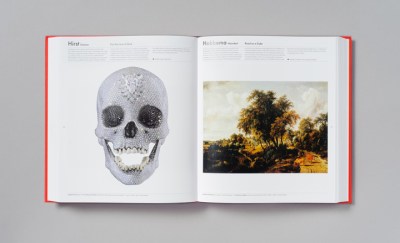

And so it goes on throughout the book, with beautiful art by great artists following or preceding ugly art by poseurs and charlatans. But some of the modern art is attractive or interesting, like Bridget Riley’s eye-alive Cataract 3 (1961) and Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God (2006). Riley and Hirst aren’t great and Hirst at least is more like an entrepreneur than an artist, but their art here is something that rewards the eye. So is Riley’s art elsewhere, as newcomers to her work might guess from the single example here. That is one of the purposes of a guide like this: to invite – or discourage – further investigation. I vaguely remember seeing the beautiful still-life of a boiled lobster, drinking horn and peeled lemon on page 283 before, but I wouldn’t have recognized the name of the Dutch artist: Willem Kalf (1619-93).

Elsewhere, I was surprised and pleased to see an old favourite:

John Atkinson Grimshaw and his

Nightfall on the Thames (1880). Many more people know Grimshaw’s atmospheric and eerie art than know his name, because it often appears on book-covers and as illustrations. If Phaidon are including him in popular guides with giants like Da Vinci, Dürer, Raphael and Titian, perhaps he’ll return to his previous fame. I certainly hope so.

Finding Grimshaw here made a good guide even better. The short texts above each art-work pack in a surprising amount of information and anecdote too. What you learn from the texts raises some interesting questions. For example: Why has one small nation contributed so much to the world’s treasury of art? From Van Eyck to Van Gogh by way of Hieronymus Bosch and Jan Vermeer, Holland is comparable to Italy in its importance. But only in painting, not sculpture or architecture. There aren’t just patterns of pigment, texture and geometry in this book: there are patterns of DNA, culture and evolution too. Brilliant, beautiful and banal; skilful, subtle and slapdash: The Art Book has all that and more. It puts jewels inside your skull.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• Ai Wei to Hell — How to Read Contemporary Art, Michael Wilson

• Eyck’s Eyes — Van Eyck, Simone Ferrari

• Face Paint — A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, Laura Cumming