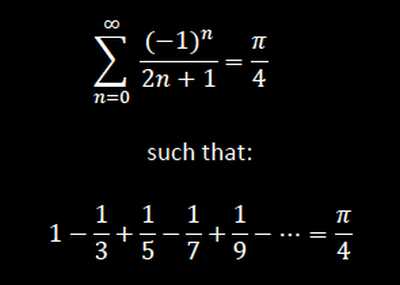

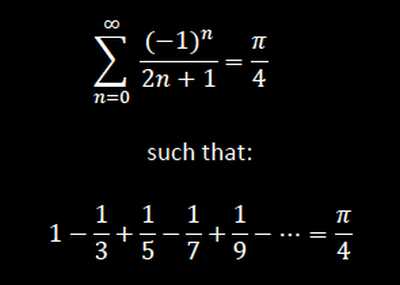

Leibniz's beautiful formula for π using odd reciprocals (image)

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Leibniz formula for π at Wikipedia

Leibniz's beautiful formula for π using odd reciprocals (image)

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Leibniz formula for π at Wikipedia

Here’s the simplest possible Egyptian fraction summing to 1:

1 = 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/6 = egypt(2,3,6)

But how many times does 1 = egypt()? Infinitely often, as is very easy to prove. Take this equation:

1/6 – 1/7 = 1/42

For any 1/n, 1/n – 1/(n+1) = 1/(n*(n+1)) = 1/(n^2 + n). In the case of 1/6, the formula means that you can re-write egypt(2,3,6) like this:

1 = egypt(2,3,7,42) = 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/42

Now try these equations:

1/6 – 1/8 = 1/24

1/6 – 1/9 = 1/18

1/6 – 1/10 = 1/15

Which lead to these re-writes of egypt(2,3,6):

1 = egypt(2,3,8,24)

1 = egypt(2,3,9,18)

1 = egypt(2,3,10,15)

Alternatively, you can expand the 1/3 of egypt(2,3,6):

1/3 – 1/4 = 1/12

Therefore:

1 = egypt(2,4,6,12)

And the 1/12 opens all these possibilities:

1/12 – 1/13 = 1/156 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,13,156)

1/12 – 1/14 = 1/84 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,14,84)

1/12 – 1/15 = 1/60 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,15,60)

1/12 – 1/16 = 1/48 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,16,48)

1/12 – 1/18 = 1/36 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,18,36)

1/12 – 1/20 = 1/30 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,20,30)

1/12 – 1/21 = 1/28 → 1 = egypt(2,4,6,21,28)

So you can expand an Egyptian fraction for ever. If you stick to expanding the 1/6 to 1/7 + 1/42, then the 1/42 to 1/43 + 1/1806 and so on, you get this:

1 = egypt(2,3,6)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,42)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,43,1806)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,43,1807,3263442)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,43,1807,3263443,10650056950806)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,43,1807,3263443,10650056950807,113423713055421844361000442)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,43,1807,3263443,10650056950807,113423713055421844361000443,12864938683278671740537145998360961546653259485195806)

1 = egypt(2,3,7,43,1807,3263443,10650056950807,113423713055421844361000443,12864938683278671740537145998360961546653259485195807,165506647324519964198468195444439180017513152706377497841851388766535868639572406808911988131737645185442)

[…]

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• A000058, Sylvester’s Sequence, at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, with more details on the numbers above

Pre-previously on Overlord-of-the-Über-Feral, I looked at patterns like these, where sums of consecutive integers, sum(n1..n2), yield a number, n1n2, whose digits reproduce those of n1 and n2:

15 = sum(1..5)

27 = sum(2..7)

429 = sum(4..29)

1353 = sum(13..53)

1863 = sum(18..63)

Numbers like those can be called narcissistic, because in a sense they gaze back at themselves. Now I’ve looked at sums of consecutive reciprocals and found comparable narcissistic patterns:

0.45 = sum(1/4..1/5)

1.683... = sum(1/16..1/83)

0.361517... = sum(1/361..1/517)

3.61316... = sum(1/36..1/1316)

4.22847... = sum(1/42..1/2847)

3.177592... = sum(1/317..1/7592)

8.30288... = sum(1/8..1/30288)

Because the sum of consecutive reciprocals, 1/1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4…, is called the harmonic series, I’ve decided to call these numbers harcissistic = harmonic + narcissistic.

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum

Why did I put “Caveat Lector” (meaning “let the reader beware”) in the title of this post? Because it’s likely that some (or even most) fluent readers of English will misread the preceding word, “Harcissism”, as “Narcissism”.

Previously Pre-Posted (Please Peruse)

• Fair Pairs — looking at patterns like 1353 = sum(13..53)

77

Every number greater than 77 is the sum of integers, the sum of whose reciprocals is 1.

For example, 78 = 2 + 6 + 8 + 10 + 12 + 40 and 1/2 + 1/6 + 1/8 + 1/10 + 1/12 + 1/40 = 1.

R.L. Graham, “A Theorem on Partitions”, Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society, 1963; quoted in Le Lionnais, 1983.

• From David Wells’ Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Mathematics (1986)

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum…

The title of this post is a pun on the gargantuan Graham’s number, described by the same American mathematician and famous among math-fans for its mindboggling size. “Le Lionnais, 1983” must refer to a book called Les Nombres remarquables by the French mathematician François Le Lionnais (1901-84).

In his Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986), David Wells says that 142857 is “beloved of all recreational mathematicians”. He then says it’s the decimal period of the reciprocal of the fourth prime: “1/7 = 0·142857142857142…” And the reciprocal has maximum period. There are 6 = 7-1 digits before repetition begins, unlike the earlier prime reciprocals:

1/2 = 0·5

1/3 = 0·333...

1/5 = 0·2

1/7 = 0·142857 142857 142...

In other words, all possible remainders appear when you calculate the decimals of 1/7:

1*10 / 7 = 1 remainder 3 → 0·1

3*10 / 7 = 4 remainder 2 → 0·14

2*10 / 7 = 2 remainder 6 → 0·142

6*10 / 7 = 8 remainder 4 → 0·1428

4*10 / 7 = 5 remainder 5 → 0·14285

5*10 / 7 = 7 remainder 1 → 0·142857

1*10 / 7 = 1 remainder 3 → 0·142857 1

3*10 / 7 = 4 remainder 2 → 0·142857 14

2*10 / 7 = 2 remainder 6 → 0·142857 142...

That happens again with 1/17 and 1/19, but Wells says that “surprisingly, there is no known method of predicting which primes have maximum period.” It’s a simple question that involves some deep mathematics. Looking at prime reciprocals is like peering through a small window into a big room. Some things are easy to see, some are difficult and some are presently impossible.

In his discussion of 142857, Wells mentions one way of peering through a period pane: “The sequence of digits also makes a striking pattern when the digits are arranged around a circle.” Here is the pattern, with ten points around the circle representing the digits 0 to 9:

The digits of 1/7 = 0·142857142…

But I prefer, for further peers through the period-panes, to create the period-panes using remainders rather than digits. That is, the number of points around the circle is determined by the prime itself rather than the base in which the reciprocal is calculated:

The remainders of 1/7 = 1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5…

Period-panes can look like butterflies or bats or bivalves or spiders or crabs or even angels. Try the remainders of 1/13. This prime reciprocal doesn’t have maximum period: 1/13 = 0·076923 076923 076923… So there are only six remainders, creating this pattern:

remainders(1/13) = 1, 10, 9, 12, 3, 4

The multiple 2/13 has different remainders and creates a different pattern:

remainders(2/13) = 2, 7, 5, 11, 6, 8

But 1/17, 1/19 and 1/23 all have maximum period and yield these period-panes:

remainders(1/17) = 1, 10, 15, 14, 4, 6, 9, 5, 16, 7, 2, 3, 13, 11, 8, 12

remainders(1/19) = 1, 10, 5, 12, 6, 3, 11, 15, 17, 18, 9, 14, 7, 13, 16, 8, 4, 2

remainders(1/23) = 1, 10, 8, 11, 18, 19, 6, 14, 2, 20, 16, 22, 13, 15, 12, 5, 4, 17, 9, 21, 3, 7

It gets mixed again with the prime 73, which doesn’t have maximum period and yields a plethora of period-panes (some patterns repeat with different n * 1/73, so I haven’t included them):

remainders(1/73)

remainders(2/73)

remainders(3/73)

remainders(4/73)

remainders(5/73)

remainders(6/73)

remainders(9/73)

remainders(11/73) (identical to pattern of 5/73)

remainders(12/73)

remainders(18/73)

101 yields a plethora of period-panes, but they’re variations on a simple theme. They look like flapping wings in this animated gif:

remainders of n/101 (animated)

The remainders of 137 yield more complex period-panes:

remainders of n/137 (animated)

And what about different bases? Here are period-panes for the remainders of 1/17 in bases 2 to 16:

remainders(1/17) in base 2

remainders(1/17) in b3

remainders(1/17) in b4

remainders(1/17) in b5

remainders(1/17) in b6

remainders(1/17) in b7

remainders(1/17) in b8

remainders(1/17) in b9

remainders(1/17) in b10

remainders(1/17) in b11

remainders(1/17) in b12

remainders(1/17) in b13

remainders(1/17) in b14

remainders(1/17) in b15

remainders(1/17) in b16

remainders(1/17) in bases 2 to 16 (animated)

But the period-panes so far have given a false impression. They’ve all been symmetrical. That isn’t the case with all the period-panes of n/19:

remainders(1/19) in b2

remainders(1/19) in b3

remainders(1/19) in b4 = 1, 4, 16, 7, 9, 17, 11, 6, 5 (asymmetrical)

remainders(1/19) in b5 = 1, 5, 6, 11, 17, 9, 7, 16, 4 (identical pattern to that of b4)

remainders(1/19) in b6

remainders(1/19) in b7

remainders(1/19) in b8

remainders(1/19) in b9

remainders(1/19) in b10 (identical pattern to that of b2)

remainders(1/19) in b11

remainders(1/19) in b12

remainders(1/19) in b13

remainders(1/19) in b14

remainders(1/19) in b15

remainders(1/19) in b16

remainders(1/19) in b17

remainders(1/19) in b18

remainders(1/19) in bases 2 to 18 (animated)

Here are a few more period-panes in different bases:

remainders(1/11) in b2

remainders(1/11) in b7

remainders(1/13) in b6

remainders(1/43) in b6

remainders in b2 for reciprocals of 29, 37, 53, 59, 61, 67, 83, 101, 107, 131, 139, 149 (animated)

And finally, to performativize the pun of “period pane”, here are some period-panes for 1/29, whose maximum period will be 28 (NASA says that the “Moon takes about one month to orbit Earth … 27.3 days to complete a revolution, but 29.5 days to change from New Moon to New Moon”):

remainders(1/29) in b4

remainders(1/29) in b5

remainders(1/29) in b8

remainders(1/29) in b9

remainders(1/29) in b11

remainders(1/29) in b13

remainders(1/29) in b14

remainders(1/29) in various bases (animated)

This is a regular nonagon (a polygon with nine sides):

A nonagon or enneagon (from Wikipedia)

And this is the endlessly repeating decimal of the reciprocal of 7:

1/7 = 0.142857142857142857142857…

What is the curious connection between 1/7 and nonagons? If I’d been asked that a week ago, I’d’ve had no answer. Then I found a curious connection when I was looking at the leading digits of polygonal numbers. A polygonal number is a number that can be represented in the form of a polygon. Triangular numbers look like this:

* = 1*

** = 3*

**

*** = 6*

**

***

**** = 10*

**

***

****

***** = 15

By looking at the shapes rather than the numbers, it’s easy to see that you generate the triangular numbers by simply summing the integers:

1 = 1

1+2=3

1+2+3=6

1+2+3+4=10

1+2+3+4+5=15

Now try the square numbers:

* = 1**

** = 4***

***

*** = 9****

****

****

**** = 16*****

*****

*****

*****

***** = 25

You generate the square numbers by summing the odd integers:

1 = 1

1+3 = 4

1+3+5 = 9

1+3+7 = 16

1+3+7+9 = 25

Next come the pentagonal numbers, the hexagonal numbers, the heptagonal numbers, and so on. I was looking at the leading digits of these numbers and trying to find patterns. For example, when do the leading digits of the k-th triangular number, tri(k), match the digits of k? This is when:

tri(1) = 1

tri(19) = 190

tri(199) = 19900

tri(1999) = 1999000

tri(19999) = 199990000

tri(199999) = 19999900000

[...]

That pattern is easy to explain. The formula for the k-th polygonal number is k * ((pn-2)*k + (4-pn)) / 2, where pn = 3 for the triangular numbers, 4 for the square numbers, 5 for the pentagonal numbers, and so on. Therefore the k-th triangular number is k * (k + 1) / 2. When k = 19, the formula is 19 * (19 + 1) / 2 = 19 * 20 / 2 = 19 * 10 = 190. And so on. Now try the pol(k) = leaddig(pol(k)) for higher polygonal numbers. The patterns are easy to predict until you get to the nonagonal numbers:

square(10) = 100

square(100) = 10000

square(1000) = 1000000

square(10000) = 100000000

square(100000) = 10000000000

[...]

pentagonal(7) = 70

pentagonal(67) = 6700

pentagonal(667) = 667000

pentagonal(6667) = 66670000

pentagonal(66667) = 6666700000

[...]

hexagonal(6) = 66

hexagonal(51) = 5151

hexagonal(501) = 501501

hexagonal(5001) = 50015001

hexagonal(50001) = 5000150001

[...]

heptagonal(5) = 55

heptagonal(41) = 4141

heptagonal(401) = 401401

heptagonal(4001) = 40014001

heptagonal(40001) = 4000140001

[...]

octagonal(4) = 40

octagonal(34) = 3400

octagonal(334) = 334000

octagonal(3334) = 33340000

octagonal(33334) = 3333400000

[...]

nonagonal(4) = 46

nonagonal(30) = 3075

nonagonal(287) = 287574

nonagonal(2858) = 28581429

nonagonal(28573) = 2857385719

nonagonal(285715) = 285715000000

nonagonal(2857144) = 28571444285716

nonagonal(28571430) = 2857143071428575

nonagonal(285714287) = 285714287571428574

nonagonal(2857142858) = 28571428581428571429

nonagonal(28571428573) = 2857142857385714285719

nonagonal(285714285715) = 285714285715000000000000

nonagonal(2857142857144) = 28571428571444285714285716

nonagonal(28571428571430) = 2857142857143071428571428575

nonagonal(285714285714287) = 285714285714287571428571428574

nonagonal(2857142857142858) = 28571428571428581428571428571429

nonagonal(28571428571428573) = 2857142857142857385714285714285719

nonagonal(285714285714285715) = 285714285714285715000000000000000000

nonagonal(2857142857142857144) = 28571428571428571444285714285714285716

nonagonal(28571428571428571430) = 2857142857142857143071428571428571428575

[...]

What’s going on with the leading digits of the nonagonals? Well, they’re generating a different reciprocal. Or rather, they’re generating the multiple of a different reciprocal:

1/7 * 2 = 2/7 = 0.285714285714285714285714285714...

And why does 1/7 have this curious connection with the nonagonal numbers? Because the nonagonal formula is k * (7k-5) / 2 = k * ((9-2) * k + (4-pn)) / 2. Now look at the pentadecagonal numbers, where pn = 15:

pentadecagonal(1538461538461538461540) = 153846153846153846154069230769230769230769302/13 = 0.153846153846153846153846153846...

pentadecagonal formula = k * (13k - 11) / 2 = k * ((15-2)*k + (4-15)) / 2

Penultimately, let’s look at the icosikaihenagonal numbers, where pn = 21:

icosikaihenagonal(2) = 21

icosikaihenagonal(12) = 1266

icosikaihenagonal(107) = 107856

icosikaihenagonal(1054) = 10544743

icosikaihenagonal(10528) = 1052878960

icosikaihenagonal(105265) = 105265947385

icosikaihenagonal(1052633) = 10526335263165

icosikaihenagonal(10526317) = 1052631731578951

icosikaihenagonal(105263159) = 105263159210526318

icosikaihenagonal(1052631580) = 10526315801578947370

icosikaihenagonal(10526315791) = 1052631579163157894746

icosikaihenagonal(105263157896) = 105263157896368421052636

icosikaihenagonal(1052631578949) = 10526315789497368421052643

icosikaihenagonal(10526315789475) = 1052631578947542105263157900

icosikaihenagonal(105263157894738) = 105263157894738263157894736845

icosikaihenagonal(1052631578947370) = 10526315789473706842105263157905

icosikaihenagonal(10526315789473686) = 1052631578947368689473684210526331

icosikaihenagonal(105263157894736843) = 105263157894736843000000000000000000

icosikaihenagonal(1052631578947368422) = 10526315789473684220526315789473684211

icosikaihenagonal(10526315789473684212) = 10526315789473684212578947368421052631662/19 = 0.1052631578947368421052631579

icosikaihenagonal formula = k * (19k - 17) / 2 = k * ((21-2)*k + (4-21)) / 2

And ultimately, let’s look at this other pattern in the leading digits of the triangular numbers, which I can’t yet explain at all:

tri(904) = 409060

tri(6191) = 19167336

tri(98984) = 4898965620

tri(996694) = 496699963165

tri(9989894) = 49898996060565

tri(99966994) = 4996699994681515

tri(999898994) = 499898999601055515

tri(9999669994) = 49996699999451815015

tri(99998989994) = 4999898999960055555015

tri(999996699994) = 499996699999945018150015

tri(9999989899994) = 49999898999996005055550015

tri(99999966999994) = 4999996699999994500181500015

tri(999999898999994) = 499999898999999600500555500015

[...]

Here’s a sequence. What’s the next number?

1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1...

Here’s another sequence. What’s the next number?

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34...

Those aren’t trick questions, so the answers are 1 and 55, respectively. The second sequence is the famous Fibonacci sequence, where each number after [0,1] is the sum of the previous two numbers.

Now try dividing each of those sequences by powers of 2 and summing the results, like this:

1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + 1/128 + 1/256 + 1/512 + 1/1024 + 1/2048 + 1/4096 + 1/8192 + 1/16384 + 1/32768 + 1/65536 + 1/131072 + 1/262144 + 1/524288 + 1/1048576 +... = ?

0/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 2/16 + 3/32 + 5/64 + 8/128 + 13/256 + 21/512 + 34/1024 + 55/2048 + 89/4096 + 144/8192 + 233/16384 + 377/32768 + 610/65536 + 987/131072 + 1597/262144 + 2584/524288 + 4181/1048576 +... = ?

What are the sums? I was surprised to learn that they’re identical:

1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + 1/128 + 1/256 + 1/512 + 1/1024 + 1/2048 + 1/4096 + 1/8192 + 1/16384 + 1/32768 + 1/65536 + 1/131072 + 1/262144 + 1/524288 + 1/1048576 +... = 1

0/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 2/16 + 3/32 + 5/64 + 8/128 + 13/256 + 21/512 + 34/1024 + 55/2048 + 89/4096 + 144/8192 + 233/16384 + 377/32768 + 610/65536 + 987/131072 + 1597/262144 + 2584/524288 + 4181/1048576 +... = 1

I discovered this when I was playing with an old scientific calculator and calculated these sums:

5^2 + 2^2 = 29

5^2 + 4^2 = 41

5^2 + 6^2 = 61

5^2 + 8^2 = 89

The sums are all prime numbers. Then I idly calculated the reciprocal of 1/89:

1/89 = 0·011235955056179775...

The digits 011235… are the start of the Fibonacci sequence. It seems to go awry after that, but I remembered what David Wells had said in his wonderful Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986): “89 is the 11th Fibonacci number, and the period of its reciprocal is generated by the Fibonacci sequence: 1/89 = 0·11235…” He means that the Fibonacci sequence generates the digits of 1/89 like this, when you sum the columns and move carries left as necessary:

0

↓1

↓↓1

↓↓↓2

↓↓↓↓3

↓↓↓↓↓5

↓↓↓↓↓↓8

↓↓↓↓↓↓13

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓21

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓34

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓55

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓89...

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓

0112359550...

I tried this method of summing the Fibonacci sequence in other bases. Although it was old, the scientific calculator was crudely programmable. And it helpfully converted the sum into a final fraction once there were enough decimal digits:

0/3 + 1/32 + 1/33 + 2/34 + 3/35 + 5/36 + 8/37 + 13/38 + 21/39 + 34/310 + 55/311 + 89/312 + 144/313 + 233/314 + 377/315 + 610/316 + 987/317 + 1597/318 + 2584/319 + 4181/320 +... = 1/5 = 0·012101210121012101210 in b3

0/4 + 1/42 + 1/43 + 2/44 + 3/45 + 5/46 + 8/47 + 13/48 + 21/49 + 34/410 + 55/411 + 89/412 + 144/413 + 233/414 + 377/415 + 610/416 + 987/417 + 1597/418 + 2584/419 + 4181/420 +... = 1/11 = 0·011310113101131011310 in b4

0/5 + 1/52 + 1/53 + 2/54 + 3/55 + 5/56 + 8/57 + 13/58 + 21/59 + 34/510 + 55/511 + 89/512 + 144/513 + 233/514 + 377/515 + 610/516 + 987/517 + 1597/518 + 2584/519 + 4181/520 +... = 1/19 = 0·011242141011242141011 in b5

0/6 + 1/62 + 1/63 + 2/64 + 3/65 + 5/66 + 8/67 + 13/68 + 21/69 + 34/610 + 55/611 + 89/612 + 144/613 + 233/614 + 377/615 + 610/616 + 987/617 + 1597/618 + 2584/619 + 4181/620 +... = 1/29 = 0·011240454431510112404 in b6

0/7 + 1/72 + 1/73 + 2/74 + 3/75 + 5/76 + 8/77 + 13/78 + 21/79 + 34/710 + 55/711 + 89/712 + 144/713 + 233/714 + 377/715 + 610/716 + 987/717 + 1597/718 + 2584/719 + 4181/720 +... = 1/41 = 0·011236326213520225056 in b7

It was interesting to see that all the reciprocals so far were of primes. I carried on:

0/8 + 1/82 + 1/83 + 2/84 + 3/85 + 5/86 + 8/87 + 13/88 + 21/89 + 34/810 + 55/811 + 89/812 + 144/813 + 233/814 + 377/815 + 610/816 + 987/817 + 1597/818 + 2584/819 + 4181/820 +... = 1/55 = 0·011236202247440451710 in b8

Not a prime reciprocal, but a reciprocal of a Fibonacci number. Here are some more sums:

0/9 + 1/92 + 1/93 + 2/94 + 3/95 + 5/96 + 8/97 + 13/98 + 21/99 + 34/910 + 55/911 + 89/912 + 144/913 + 233/914 + 377/915 + 610/916 + 987/917 + 1597/918 + 2584/919 + 4181/920 +... = 1/71 (another prime) = 0·011236067540450563033 in b9

0/10 + 1/102 + 1/103 + 2/104 + 3/105 + 5/106 + 8/107 + 13/108 + 21/109 + 34/1010 + 55/1011 + 89/1012 + 144/1013 + 233/1014 + 377/1015 + 610/1016 + 987/1017 + 1597/1018 + 2584/1019 + 4181/1020 +... = 1/89 (and another) = 0·011235955056179775280 in b10

0/11 + 1/112 + 1/113 + 2/114 + 3/115 + 5/116 + 8/117 + 13/118 + 21/119 + 34/1110 + 55/1111 + 89/1112 + 144/1113 + 233/1114 + 377/1115 + 610/1116 + 987/1117 + 1597/1118 + 2584/1119 + 4181/1120 +... = 1/109 (and another) = 0·011235942695392022470 in b11

0/12 + 1/122 + 1/123 + 2/124 + 3/125 + 5/126 + 8/127 + 13/128 + 21/129 + 34/1210 + 55/1211 + 89/1212 + 144/1213 + 233/1214 + 377/1215 + 610/1216 + 987/1217 + 1597/1218 + 2584/1219 + 4181/1220 +... = 1/131 (and another) = 0·011235930336A53909A87 in b12

0/13 + 1/132 + 1/133 + 2/134 + 3/135 + 5/136 + 8/137 + 13/138 + 21/139 + 34/1310 + 55/1311 + 89/1312 + 144/1313 + 233/1314 + 377/1315 + 610/1316 + 987/1317 + 1597/1318 + 2584/1319 + 4181/1320 +... = 1/155 (not a prime or a Fibonacci number) = 0·01123591ACAA861794044 in b13

The reciprocals go like this:

1/1, 1/5, 1/11, 1/19, 1/29, 1/41, 1/55, 1/71, 1/89, 1/109, 1/131, 1/155...

And it should be easy to see the rule that generates them:

5 = 1 + 4

11 = 5 + 6

19 = 11 + 8

29 = 19 + 10

41 = 29 + 12

55 = 41 + 14

71 = 55 + 16

89 = 17 + 18

109 = 89 + 20

131 = 109 + 22

155 = 131 + 24

[...]

But I don’t understand why the rule applies, let alone why the Fibonacci sequence generates these reciprocals in the first place.

A021023 Decimal expansion of 1/19.

0, 5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 4, 7, 3, 6, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 4, 7, 3, 6, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 4, 7, 3, 6, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 4, 7, 3, 6, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 4, 7, 3, 6, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0, 5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5, 7, 8 [...] The magic square that uses the decimals of 1/19 is fully magic. — A021023 at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences

In The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1987), David Wells remarks that 142857 is “a number beloved of all recreational mathematicians”. He then explains that it’s “the decimal period of 1/7: 1/7 = 0·142857142857142…” and “the first decimal reciprocal to have maximum period, that is, the length of its period is only one less than the number itself.”

Why does this happen? Because when you’re calculating 1/n, the remainders can only be less than n. In the case of 1/7, you get remainders for all integers less than 7, i.e. there are 6 distinct remainders and 6 = 7-1:

(1*10) / 7 = 1 remainder 3, therefore 1/7 = 0·1...

(3*10) / 7 = 4 remainder 2, therefore 1/7 = 0·14...

(2*10) / 7 = 2 remainder 6, therefore 1/7 = 0·142...

(6*10) / 7 = 8 remainder 4, therefore 1/7 = 0·1428...

(4*10) / 7 = 5 remainder 5, therefore 1/7 = 0·14285...

(5*10) / 7 = 7 remainder 1, therefore 1/7 = 0·142857...

(1*10) / 7 = 1 remainder 3, therefore 1/7 = 0·1428571...

(3*10) / 7 = 4 remainder 2, therefore 1/7 = 0·14285714...

(2*10) / 7 = 2 remainder 6, therefore 1/7 = 0·142857142...

Mathematicians know that reciprocals with maximum period can only be prime reciprocals and with a little effort you can work out whether a prime will yield a maximum period in a particular base. For example, 1/7 has maximum period in bases 3, 5, 10, 12 and 17:

1/21 = 0·010212010212010212... in base 3

1/12 = 0·032412032412032412... in base 5

1/7 = 0·142857142857142857... in base 10

1/7 = 0·186A35186A35186A35... in base 12

1/7 = 0·274E9C274E9C274E9C... in base 17

To see where else 1/7 has maximum period, have a look at this graph:

Period pane for primes 3..251 and bases 2..39

I call it a “period pane”, because it’s a kind of window into the behavior of prime reciprocals. But what is it, exactly? It’s a graph where the x-axis represents primes from 3 upward and the y-axis represents bases from 2 upward. The red squares along the bottom aren’t part of the graph proper, but indicate primes that first occur after a power of two: 5 after 4=2^2; 11 after 8=2^3; 17 after 16=2^4; 37 after 32=2^5; 67 after 64=2^6; and so on.

If a prime reciprocal has maximum period in a particular base, the graph has a solid colored square. Accordingly, the purple square at the bottom left represents 1/7 in base 10. And as though to signal the approval of the goddess of mathematics, the graph contains a lower-case b-for-base, which I’ve marked in green. Here are more period panes in higher resolution (open the images in a new window to see them more clearly):

Period pane for primes 3..587 and bases 2..77

Period pane for primes 3..1303 and bases 2..152

An interesting pattern has begun to appear: note the empty lanes, free of reciprocals with maximum period, that stretch horizontally across the period panes. These lanes are empty because there are no prime reciprocals with maximum period in square bases, that is, bases like 4, 9, 25 and 36, where 4 = 2*2, 9 = 3*3, 25 = 5*5 and 36 = 6*6. I don’t know why square bases don’t have max-period prime reciprocals, but it’s probably obvious to anyone with more mathematical nous than me.

Period pane for primes 3..2939 and bases 2..302

Period pane for primes 3..6553 and bases 2..602

Like the Ulam spiral, other and more mysterious patterns appear in the period panes, hinting at the hidden regularities in the primes.

Abundance often overwhelms, but restriction reaps riches. That’s true in mathematics and science, where you can often understand the whole better by looking at only a part of it first — restriction reaps riches. Egyptian fractions are one example in maths. In ancient Egypt, you could have any kind of fraction you liked so long as it was a reciprocal like 1/2, 1/3, 1/4 or 1/5 (well, there were two exceptions: 2/3 and 3/4 were also allowed).

So when mathematicians speak of “Egyptian fractions”, they mean those fractions that can be represented as a sum of reciprocals. Egyptian fractions are restricted and that reaps riches. Here’s one example: how many ways can you add n distinct reciprocals to make 1? When n = 1, there’s one way to do it: 1/1. When n = 2, there’s no way to do it, because 1 – 1/2 = 1/2. Therefore the summed reciprocals aren’t distinct: 1/2 + 1/2 = 1. After that, 1 – 1/3 = 2/3, 1 – 1/4 = 3/4, and so on. By the modern meaning of “Egyptian fraction”, there’s no solution for n = 2.

However, when n = 3, there is a way to do it:

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/6 = 1

But that’s the only way. When n = 4, things get better:

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/12 = 1

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/10 + 1/15 = 1

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/18 = 1

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/20 = 1

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/24 = 1

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/42 = 1

What about n = 5, n = 6 and so on? You can find the answer at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS), where sequence A006585 is described as “Egyptian fractions: number of solutions to 1 = 1/x1 + … + 1/xn in positive integers x1 < … < xn”. The sequence is one of the shortest and strangest at the OEIS:

• 1, 0, 1, 6, 72, 2320, 245765, 151182379

When n = 1, there’s one solution: 1/1. When n = 2, there’s no solution, as I showed above. When n = 3, there’s one solution again. When n = 4, there are six solutions. And the OEIS tells you how many solutions there are for n = 5, 6, 7, 8. But n >= 9 remains unknown at the time of writing.

To understand the problem, consider the three reciprocals, 1/2, 1/3 and 1/5. How do you sum them? They have different denominators, 2, 3 and 5, so you have to create a new denominator, 30 = 2 * 3 * 5. Then you have to adjust the numerators (the numbers above the fraction bar) so that the new fractions have the same value as the old:

• 1/2 = 15/30 = (2*3*5 / 2) / 30

• 1/3 = 10/30 = (2*3*5 / 3) / 30

• 1/5 = 06/30 = (2*3*5 / 5) / 30

• 15/30 + 10/30 + 06/30 = (15+10+6) / 30 = 31/30 = 1 + 1/30

Those three reciprocals don’t sum to 1. Now try 1/2, 1/3 and 1/6:

• 1/2 = 18/36 = (2*3*6 / 2) / 36

• 1/3 = 12/36 = (2*3*6 / 3) / 36

• 1/6 = 06/36 = (2*3*6 / 6) / 36

• 18/36 + 12/36 + 06/36 = (18+12+6) / 36 = 36/36 = 1

So when n = 3, the problem consists of finding three reciprocals, 1/a, 1/b and 1/c, such that for a, b, and c:

• a*b*c = a*b + a*c + b*c

There is only one solution: a = 2, b = 3 and c = 6. When n = 4, the problem consists of finding four reciprocals, 1/a, 1/b, 1/c and 1/d, such that for a, b, c and d:

• a*b*c*d = a*b*c + a*b*d + a*c*d + b*c*d

For example:

• 2*4*6*12 = 576

• 2*4*6 + 2*4*12 + 2*6*12 + 4*6*12 = 48 + 96 + 144 + 288 = 576

• 2*4*6*12 = 2*4*6 + 2*4*12 + 2*6*12 + 4*6*12 = 576

Therefore:

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/12 = 1

When n = 5, the problem consists of finding five reciprocals, 1/a, 1/b, 1/c, 1/d and 1/e, such that for a, b, c, d and e:

• a*b*c*d*e = a*b*c*d + a*b*c*e + a*b*d*e + a*c*d*e + b*c*d*e

There are 72 solutions and here they are:

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/10 + 1/12 + 1/15 = 1 (#1)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/9 + 1/12 + 1/18 = 1 (#2)

• 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/12 + 1/20 = 1 (#3)

• 1/3 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/20 = 1 (#4)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/12 + 1/24 = 1 (#5)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/21 + 1/28 = 1 (#6)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/21 + 1/28 = 1 (#7)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/7 + 1/14 + 1/28 = 1 (#8)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/20 + 1/30 = 1 (#9)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/20 + 1/30 = 1 (#10)

• 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/10 + 1/30 = 1 (#11)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/11 + 1/22 + 1/33 = 1 (#12)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/14 + 1/15 + 1/35 = 1 (#13)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/18 + 1/36 = 1 (#14)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/18 + 1/36 = 1 (#15)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/10 + 1/24 + 1/40 = 1 (#16)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/10 + 1/40 = 1 (#17)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/7 + 1/12 + 1/42 = 1 (#18)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/30 + 1/45 = 1 (#19)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/36 + 1/45 = 1 (#20)

• 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/9 + 1/45 = 1 (#21)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/16 + 1/48 = 1 (#22)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/16 + 1/48 = 1 (#23)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/27 + 1/54 = 1 (#24)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/42 + 1/56 = 1 (#25)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/40 + 1/60 = 1 (#26)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/10 + 1/20 + 1/60 = 1 (#27)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/15 + 1/60 = 1 (#28)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/30 + 1/60 = 1 (#29)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/15 + 1/60 = 1 (#30)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/28 + 1/70 = 1 (#31)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/36 + 1/72 = 1 (#32)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/24 + 1/72 = 1 (#33)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/9 + 1/72 = 1 (#34)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/14 + 1/84 = 1 (#35)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/14 + 1/84 = 1 (#36)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/33 + 1/88 = 1 (#37)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/10 + 1/18 + 1/90 = 1 (#38)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/78 + 1/91 = 1 (#39)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/32 + 1/96 = 1 (#40)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/22 + 1/99 = 1 (#41)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/25 + 1/100 = 1 (#42)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/70 + 1/105 = 1 (#43)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/11 + 1/15 + 1/110 = 1 (#44)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/30 + 1/120 = 1 (#45)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/24 + 1/120 = 1 (#46)

• 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/8 + 1/120 = 1 (#47)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/63 + 1/126 = 1 (#48)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/21 + 1/126 = 1 (#49)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/60 + 1/140 = 1 (#50)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/7 + 1/10 + 1/140 = 1 (#51)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/12 + 1/13 + 1/156 = 1 (#52)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/13 + 1/156 = 1 (#53)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/56 + 1/168 = 1 (#54)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/28 + 1/168 = 1 (#55)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/20 + 1/180 = 1 (#56)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/54 + 1/189 = 1 (#57)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/27 + 1/216 = 1 (#58)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/22 + 1/220 = 1 (#59)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/11 + 1/14 + 1/231 = 1 (#60)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/51 + 1/238 = 1 (#61)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/10 + 1/16 + 1/240 = 1 (#62)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/49 + 1/294 = 1 (#63)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/26 + 1/312 = 1 (#64)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/48 + 1/336 = 1 (#65)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/9 + 1/19 + 1/342 = 1 (#66)

• 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/21 + 1/420 = 1 (#67)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/46 + 1/483 = 1 (#68)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/8 + 1/25 + 1/600 = 1 (#69)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/45 + 1/630 = 1 (#70)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/44 + 1/924 = 1 (#71)

• 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/7 + 1/43 + 1/1806 = 1 (#72)

All the sums start with 1/2 except for one:

• 1/2 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/12 + 1/20 = 1 (#3)

• 1/3 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/20 = 1 (#4)

Here are the solutions in another format:

(2,4,10,12,15), (2,4,9,12,18), (2,5,6,12,20), (3,4,5,6,20), (2,4,8,12,24), (2,3,12,21,28), (2,4,6,21,28), (2,4,7,14,28), (2,3,12,20,30), (2,4,6,20,30), (2,5,6,10,30), (2,3,11,22,33), (2,3,14,15,35), (2,3,12,18,36), (2,4,6,18,36), (2,3,10,24,40), (2,4,8,10,40), (2,4,7,12,42), (2,3,9,30,45), (2,4,5,36,45), (2,5,6,9,45), (2,3,12,16,48), (2,4,6,16,48), (2,3,9,27,54), (2,3,8,42,56), (2,3,8,40,60), (2,3,10,20,60), (2,3,12,15,60), (2,4,5,30,60), (2,4,6,15,60), (2,4,5,28,70), (2,3,8,36,72), (2,3,9,24,72), (2,4,8,9,72), (2,3,12,14,84), (2,4,6,14,84), (2,3,8,33,88), (2,3,10,18,90), (2,3,7,78,91), (2,3,8,32,96), (2,3,9,22,99), (2,4,5,25,100), (2,3,7,70,105), (2,3,11,15,110), (2,3,8,30,120), (2,4,5,24,120), (2,5,6,8,120), (2,3,7,63,126), (2,3,9,21,126), (2,3,7,60,140), (2,4,7,10,140), (2,3,12,13,156), (2,4,6,13,156), (2,3,7,56,168), (2,3,8,28,168), (2,3,9,20,180), (2,3,7,54,189), (2,3,8,27,216), (2,4,5,22,220), (2,3,11,14,231), (2,3,7,51,238), (2,3,10,16,240), (2,3,7,49,294), (2,3,8,26,312), (2,3,7,48,336), (2,3,9,19,342), (2,4,5,21,420), (2,3,7,46,483), (2,3,8,25,600), (2,3,7,45,630), (2,3,7,44,924), (2,3,7,43,1806)

Note

Strictly speaking, there are two solutions for n = 2 in genuine Egyptian fractions, because 1/3 + 2/3 = 1 and 1/4 + 3/4 = 1. As noted above, 2/3 and 3/4 were permitted as fractions in ancient Egypt.