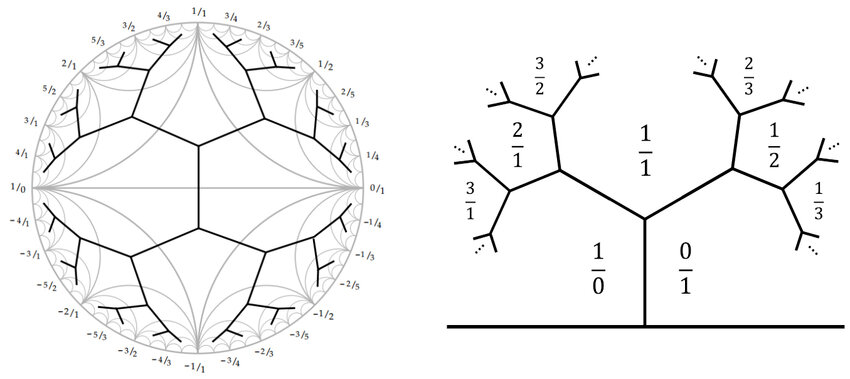

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.” So said HPL in “The Call of Cthulhu” (1926). But I’d still like to correlate the contents of mine a bit better. For example, I knew that φ, the golden ratio, is the most irrational of all numbers, in that it is the slowest to be approximated with rational fractions. And I also knew that continued fractions, or CFs, were a way of representing both rationals and irrationals as a string of numbers, like this:

contfrac(10/7) = [1; 2, 3]

10/7 = 1 + 1/(2 + 1/3)

10/7 = 1.428571428571…

contfrac(3/5) = [0; 1, 1, 2]

4/5 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))

4/5 = 0.8

contfrac(11/8) = [1; 2, 1, 2]

11/8 = 1 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/2))

11/8 = 1.375

contfrac(4/7) = [0; 1, 1, 3]

4/7 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/3))

4/7 = 0.57142857142…

contfrac(17/19) = [0; 1, 8, 2]

17/19 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(8 + 1/2))

17/19 = 0.8947368421052…

contfrac(8/25) = [0; 3, 8]

8/25 = 0 + 1/(3 + 1/8)

8/25 = 0.32

contfrac(√2) = [1; 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2…] = [1; 2]

√2 = 1 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/2 + …))))))

√2 = 1.41421356237309504…

contfrac(φ) = [1; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…]

φ = 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/1 + …)))))))

φ = 1.6180339887498948…

But I didn’t correlate those two contents of my mind: the maximal irrationality of φ and the way continued fractions work.

That’s why I was surprised when I was looking at the continued fractions of 2..(n-1) / n for 3,4,5,6,7… That is, I was looking at the continued fractions of 2/3, 3/4, 2/5, 3/5, 4/5, 5/6, 2/7, 3/7… (skipping fractions like 2/4, 2/6, 3/6 etc, because they’re reducible: 2/4 = ½, 2/6 = 1/3, 3/6 = ½ etc). I wondered which fractions set successive records for the length of their continued fractions as one worked through ½, 2/3, 3/4, 2/5, 3/5, 4/5, 5/6, 2/7, 3/7… And because I hadn’t correlated the contents of my mind, I was surprised at the result. I shouldn’t have been, of course:

contfrac(1/2) = [0; 2] (cfl=1)

1/2 = 0 + 1/2

1/2 = 0.5

contfrac(2/3) = [0; 1, 2] (cfl=2)

2/3 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/2)

2/3 = 0.666666666…

contfrac(3/5) = [0; 1, 1, 2] (cfl=3)

3/5 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))

3/5 = 0.6

contfrac(5/8) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=4)

5/8 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2)))

5/8 = 0.625

contfrac(8/13) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=5)

8/13 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))))

8/13 = 0.615384615…

contfrac(13/21) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=6)

13/21 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2)))))

13/21 = 0.619047619…

contfrac(21/34) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=7)

21/34 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))))))

21/34 = 0.617647059…

contfrac(34/55) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=8)

contfrac(55/89) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=9)

contfrac(89/144) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=10)

contfrac(144/233) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=11)

contfrac(233/377) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=12)

contfrac(377/610) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=13)

contfrac(610/987) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=14)

contfrac(987/1597) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=15)

contfrac(1597/2584) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=16)

contfrac(2584/4181) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=17)

contfrac(4181/6765) = [0; 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=18)

[…]

Which n1/n2 set records for the length of their continued fractions (with n2 > n1)? It’s the successive Fibonacci fractions, fib(i)/fib(i+1), of course. I didn’t anticipate that answer because I didn’t understand φ and continued fractions properly. And I still don’t, because I’ve been surprised again today looking at palindromic CFs like these:

contfrac(2/5) = [0; 2, 2] (cfl=2)

2/5 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/2)

2/5 = 0.4

contfrac(3/8) = [0; 2, 1, 2] (cfl=3)

3/8 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/2))

3/8 = 0.375

contfrac(3/10) = [0; 3, 3] (cfl=2)

3/10 = 0 + 1/(3 + 1/3)

3/10 = 0.3

contfrac(5/12) = [0; 2, 2, 2] (cfl=3)

5/12 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/2))

5/12 = 0.416666666…

contfrac(5/13) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=4)

5/13 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2)))

5/13 = 0.384615384…

contfrac(4/15) = [0; 3, 1, 3] (cfl=3)

4/15 = 0 + 1/(3 + 1/(1 + 1/3))

4/15 = 0.266666666…

contfrac(7/16) = [0; 2, 3, 2] (cfl=3)

7/16 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(3 + 1/2))

7/16 = 0.4375

contfrac(4/17) = [0; 4, 4] (cfl=2)

4/17 = 0 + 1/(4 + 1/4)

4/17 = 0.235294117…

Again, I wondered which of these fractions set successive records for the length of their palindromic continued fractions. Here’s the answer:

contfrac(1/2) = [0; 2] (cfl=1)

1/2 = 0 + 1/2

1/2 = 0.5

contfrac(2/5) = [0; 2, 2] (cfl=2)

2/5 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/2)

2/5 = 0.4

contfrac(3/8) = [0; 2, 1, 2] (cfl=3)

3/8 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/2))

3/8 = 0.375

contfrac(5/13) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=4)

5/13 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2)))

5/13 = 0.384615384…

contfrac(8/21) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=5)

8/21 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))))

8/21 = 0.380952380…

contfrac(13/34) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=6)

13/34 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(

1 + 1/(1 + 1/2)))))

13/34 = 0.382352941..

contfrac(21/55) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=7)

21/55 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))))))

21/55 = 0.381818181…

contfrac(34/89) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=8)

contfrac(55/144) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=9)

contfrac(89/233) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=10)

contfrac(144/377) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=11)

contfrac(233/610) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=12)

contfrac(377/987) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=13)

contfrac(610/1597) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=14)

contfrac(987/2584) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=15)

contfrac(1597/4181) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=16)

contfrac(2584/6765) = [0; 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2] (cfl=17)

[…]

Now it’s the successive Fibonacci skip-one fractions, fib(i)/fib(i+2), that set records for the length of their palindromic continued fractions. But I think you’d have to be very good at maths not to be surprised by that result.

After that, I continued to be compelled by the Call of CFulhu and started to look at the CFs of Fibonacci skip-n fractions in general. That’s contfrac(fib(i)/fib(i+n)) for n = 1,2,3,… And I’ve found more interesting patterns, as I’ll describe in a follow-up post.