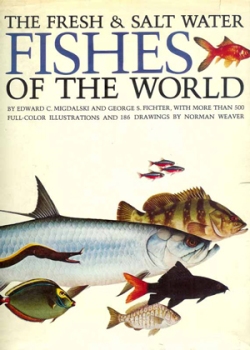

The Fresh and Salt Water Fishes of the World, Edward C. Migdalski and George S. Fichter, illustrated by Norman Weaver (1977)

The Fresh and Salt Water Fishes of the World, Edward C. Migdalski and George S. Fichter, illustrated by Norman Weaver (1977)

A big book with a big subject: fish are the most numerous and varied of the vertebrates, from the bus-sized Rhincodon typus or whale shark, which feeds its vast bulk on plankton, to the little-finger-long Vandellia cirrhosa, the parasitic catfish that can give bathers a nasty surprise by swimming into their “uro-genitary openings” – “the pain is agonizing and the fish can be removed only by surgery”. The book is full of interesting asides like that, but I doubt that readers will read every page carefully. They’ll certainly look at every page carefully, to see Norman Weaver’s gorgeous drawings, which capture both the colour and the shine of fish’s bodies. Another aspect of the enormous variation of fish is not just their differences in size, shape and colouring, but their differences in aesthetic appeal. Some are among the most beautiful of living creatures, others among the most grotesque, like the Lovecraftian horrors that literally dwell in the abyss: inhabitants of the very deep ocean like Chauliodus macouni, the Pacific viperfish, whose teeth are too long and sharp for it to close its mouth.

The crushing pressure and freezing darkness in which these fish live are alien to human beings and so are the appearance and behaviour of the fish. But fish that live in shallow water, like the hammerhead shark and the electric eel, can seem alien too and some of the strangest fish of all, the horizontally flattened rays and mantas, can even fly briefly in the open air. Some of the piscine beauties, on the other hand, like Cheirodon axelrodi, the neon-bodied cardinal tetra, are routinely kept in aquariums, but then so is the very strange Anoptichthys jordani, the blind cavefish. There’s a blind torpedo ray too, Typhlonarke aysoni, “which has no functional eyes and ‘stumps’ along the bottom on its thick, leglike ventral fins”. But the appearance, behaviour and habitat of fish aren’t the only things man finds interesting about them. Some are good eating or offer good sport and the authors often discuss both cuisine and fishing in relation to a particular species or family. That raises the second of the two questions I keep asking myself when I look at this book. The first question is: “Why are some fish so beautiful and some so ugly?” The second is: “Are fish capable of suffering, and if they are, do they suffer much?”

I don’t know if the first question can be answered or is even sensible to ask; the second will, I hope, be answered by science in the negative. It’s not pleasant to think of what a positive answer would mean, because we’ve been hooking and hauling fish from fresh and salt water for countless generations. In the past, it was for food, but when we do it today it’s often for fun. I hope the fun isn’t at fish’s expense in more than the obvious sense: that it deprives them permanently of life or, for those returned to the water, temporarily of peaceful existence. I hope the deprivation is not painful in any strong sense. Either way, fish will continue to die at each other’s fangs and to serve as food for many species of mammal and bird. Nature is red in tooth and claw, after all, but it’s a lot more beside and this is one of the books that will show you how. From luminous sharks to uncannily accurate archerfish, from what men do to fish to what fish do to men: the 315 pages of the large and lavishly illustrated Fishes of the World can offer only a glimpse into a very rich and fascinating world, but a glimpse is dazzling.

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

• Slug is a Drug — Collins Complete Guide to British Coastal Wildlife (2012)