The Neutrino Hunters: The Chase for the Ghost Particle and the Secrets of the Universe, Ray Jayawardhana (Oneworld 2013)

The Neutrino Hunters: The Chase for the Ghost Particle and the Secrets of the Universe, Ray Jayawardhana (Oneworld 2013)

An easy read on a difficult topic: Ray Jayawardhana takes some complicated ideas and makes them a pleasure to absorb. Humans have only recently discovered neutrinos, but neutrinos have always known us from the inside:

…about a hundred trillion neutrinos produced in the nuclear furnace at the Sun’s core pass through your body every second of the day and night, yet they do no harm and leave no trace. During your entire lifetime, perhaps one neutrino will interact with an atom in your body. Neutrinos travel right through the Earth unhindered, like bullets cutting through a fog. (ch. 1, “The Hunt Heats Up”, pg. 9)

In a way, “ghost particle” is a misnomer: to neutrinos, we are the ghosts, because they pass through all solid matter almost as though it’s not there:

Neutrinos are elementary particles, just like electrons that buzz around atomic nuclei or quarks that combine to make protons and neutrons. They are fundamental building blocks of matter, but they don’t remain trapped inside atoms. Also unlike their subatomic cousins, neutrinos carry no electric charge, have a tiny mass and hardly ever interact with other particles. A typical neutrino can travel through a light-year’s worth of lead without interacting with any atoms. (ch. 1, pg. 7)

That’s a lot of lead, but a little of neutrino. With a different ratio – a lot less matter and a lot more neutrino – it’s possible to detect them on earth. Because so many are passing through the earth at any moment, a large piece of matter watched for long enough will eventually catch a ghost. So neutrino-hunters sink optical sensors into the transparent ice of the Antarctic and fill huge tanks with carbon tetrachloride or water. Then they wait:

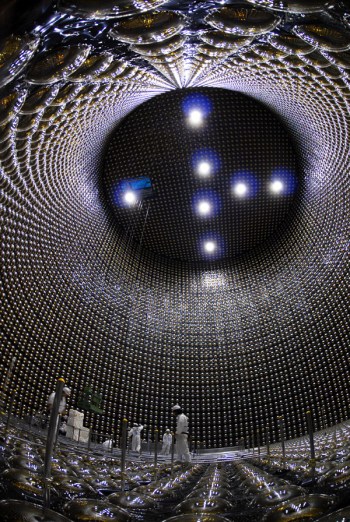

Every once in a while, a solar neutrino would collide with an electron in the water and propel it forward, like a billiard ball that’s hit head-on. The fast-moving electron would create an electromagnetic “wake”, or cone of light, along its path. The resulting pale blue radiation is called “Cherenkov radiation”, after the Russian physicist Pavel Cherenkov, who investigated the phenomenon. Phototubes lining the inside walls of the tank would register each light flash and reveal an electron’s interaction with a neutrino. The Kamiokande provided two extra bits of information to researchers: from the direction of the light cone scientists would infer the direction of the incoming neutrino and from its intensity they could determine the neutrino’s energy. (ch. 4, “Sun Underground”, pg. 95)

That’s a description of a neutrino-hunt in “3,000 tons of pure water” in a mine “150 miles west of Tokyo”: big brains around the world are obsessed with the “little neutral one”. That’s what “neutrino” means in Italian, because the particle was named by the physicist Enrico Fermi (1901-54) after the original proposal, “neutron”, was taken over by another, and much bigger, particle with no electric charge. Fermi was one of the greatest physicists of all time and oversaw the first “controlled nuclear chain reaction” at the University of Chicago in 1942. That is, he helped build the first nuclear reactor. Like the sun, reactors are rich sources of neutrinos and because neutrinos pass easily through any form of shielding, a reactor can’t be hidden from a neutrino-detector. Nor can a supernova: one of the most interesting sections of the book discusses the way exploding stars flood the universe with a lot of light and a lot more neutrinos:

Alex Friedland of the Los Alamos National Laboratory explained that a supernova is in essence a “neutrino bomb”, since the explosion releases a truly staggering number – some 10^58, or ten billion trillion trillion trillion trillion – of these particles. … In fact, the energy emitted in the form of neutrinos within a few seconds is several hundred times what the Sun emits in the form of photons over its entire lifetime of nearly 10 billion years. What’s more, during the supernova explosion, 99 percent of the precursor star’s gravitational binding energy goes into the neutrinos of all flavors, while barely half a percent appears as visible light. (ch. 6, “Exploding Star”, pg. 125)

That light is remarkably bright, but it can be blocked by interstellar dust. The neutrinos can’t, so they’re a way to detect supernovae that are otherwise invisible. However, Supernova 1987A was highly visible: a lot of photons were captured by a lot of telescopes when it flared in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Nearly four hours before that, a few neutrino-detectors had captured far fewer neutrinos:

Detecting a grand total of two dozen particles may not sound like much to crow about. But the significance of these two dozen neutrino events is underlined by the fact that they have been the subject of hundreds of scientific papers over the years. Supernova 1987A was the first time that we had observed neutrinos coming from an astronomical source other than the Sun. (ch. 6, pg. 124)

The timing of the two dozen was very important: it came before the visible explosion and “meant that astrophysicists like Bahcall and his colleagues were right about what happened during a supernova explosion” (pg. 123). That’s John Bahcall (1931-2005), an American who wanted to be a rabbi but ended up a physicist after taking a science course during his philosophy degree at Berkeley. He had predicted how many solar neutrinos his colleague Raymond Davis (1914-2006) should detect interacting with atoms in a giant tank of “dry-cleaning fluid”, as carbon tetrachloride is also known. But Davis found “only a third as many as Bahcall’s model calculation predicted” (ch. 4, pg. 90). Was Davis missing some? Was Bahcall’s model wrong? The answer would take decades to arrive, as Davis refined his apparatus and Bahcall re-checked his calculations. This book is about several kinds of interaction: between neutrinos and atoms, between theory and experiment, between mathematics and matter. Neutrinos were predicted with maths before they were detected in matter. The Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli (1900-58) produced the prediction; Davis and others did the detecting.

The Super-Kamiokande neutrino-cathedral (click for larger image)

Pauli was famously witty; another big brain in the book, the Englishman Paul Dirac (1902-84), was famously taciturn. Big brains are often strange ones too. That’s part of why they’re attracted to the very strange world of atomic physics. Jayawardhana also discusses the Italian physicist Ettore Majorana (1906-?1938), who disappeared at the age of thirty-two, and his colleague Bruno Pontecorvo (1913-93), who defected to the Soviet Union. Neutrinos are fascinating and so are the humans who have hunted for them. So is the history that surrounded them. Quantum physics was convulsing science at the same time as communism and Nazism were convulsing Europe. As the Danish physicist Niels Bohr (1885-1962) said: “Anyone who is not shocked by quantum theory has not understood it.” Modern physicists have been called a new priesthood, devoted to lofty and remote ideas incomprehensible and irrelevant to ordinary people. But ordinary people fund the devices the priests build to pursue their ideas with. And some of the neutrino-detectors pictured here are as huge and awe-inspiring as cathedrals. Some might say they’re as futile as cathedrals too. But if understanding the universe isn’t enough in itself, there may be practical uses for neutrinos on the way. At present, we have to communicate over the earth’s surface; a beam of neutrinos can travel right through the earth.

The universe is also a dangerous place: some scientists theorized that the neutrino deficit in Ray Davis’s experiments meant the sun was about to go nova. It wasn’t, but neutrinos may help the human race spot other dangers and exploit new opportunities. We still know only a fraction of what’s out there and the ghost particle is a messenger from the heart not only of supernovae and the sun, but also of the earth itself. There’s radioactivity deep in the earth, so there are neutrinos streaming upward. As methods of detecting them get better, we’ll understand the interior of the earth better. But Jayawardhana doesn’t discuss another possibility: that we might even discover advanced life down there, living under huge pressures at very high temperatures, as Arthur C. Clarke suggested in his short-story “The Fires Within” (1949).

Clarke also suggested that life could exist inside the sun. There’s presently no way of testing his ideas, but neutrinos may carry even more secrets than standard science has guessed. Either way, I think Clarke would have enjoyed this book and perhaps Jayawardhana, who’s of Sri Lankan origin, was influenced by him. Jayawardhana’s writing certainly reminds me of Clarke’s writing. It’s clear, enthusiastic and a pleasure to read, wearing its learning lightly and carrying you easily over vast stretches of space and time. The Neutrino Hunters is an excellent introduction to the hunters, the hunted and the history, with a good glossary and index too.

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

• Think Ink – Review of 50 Quantum Physics Ideas You Really Need to Know