“The uniquely unrepresentative ‘Egyptian’ fraction.” That’s what David Wells calls 2/3 = 0·666… in The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986). Why unrepresentative”? Wells goes on to explain: “the Egyptians used only unit fractions, with this one exception. All other fractional quantities were expressed as sums of unit fractions.”

A unit fraction is 1 divided by a higher integer: 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, 1/5 and so on. Modern mathematicians are interested in those sums of unit fractions that produce integers, like this:

1 = 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/6 = egypt(2,3,6)

1 = 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/12 = egypt(2,4,6,12)

1 = 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/10 + 1/15 = = egypt(2,3,10,15)

1 = egypt(2,4,10,12,15)

1 = egypt(3,4,6,10,12,15)

1 = egypt(2,3,9,18)

1 = egypt(2,4,9,12,18)

1 = egypt(3,4,6,9,12,18)

1 = egypt(2,6,9,10,15,18)

1 = egypt(3,4,9,10,12,15,18)

1 = egypt(2,4,5,20)

1 = egypt(3,4,5,6,20)

1 = egypt(2,5,6,12,20)

1 = egypt(3,4,5,10,15,20)

1 = egypt(2,5,10,12,15,20)

1 = egypt(3,5,6,10,12,15,20)

1 = egypt(3,4,5,9,18,20)

1 = egypt(2,5,9,12,18,20)

1 = egypt(3,5,6,9,12,18,20)

1 = egypt(4,5,6,9,10,15,18,20)2 = egypt(2,3,4,5,6,8,9,10,15,18,20,24)

2 = 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 + 1/5 + 1/6 + 1/8 + 1/9 + 1/10 + 1/15 + 1/18 + 1/20 + 1/24

Sums-to-integers like those are called Egyptian fractions, for short. I looked for some such sums that included 1/666:

1 = egypt(2,3,7,63,222,518,666)

1 = egypt(2,3,8,36,111,296,666)

1 = egypt(2,3,9,20,444,555,666)

1 = egypt(2,3,9,21,222,518,666)

1 = egypt(2,3,9,24,111,296,666)

1 = egypt(2,3,9,26,74,481,666)

1 = egypt(2,4,8,9,111,296,666)

And I looked for Egyptian fractions whose denominators summed to rep-digits like 111 and 666 (denominators are the bit below the stroke of 1/3 or 2/3, where the bit above is called the numerator):

1 = egypt(4,6,7,9,10,14,15,18,28)

111 = 4+6+7+9+10+14+15+18+28

1 = egypt(3,6,8,9,10,15,21,24,126)

222 = 3+6+8+9+10+15+21+24+126

1 = egypt(2,6,8,12,16,17,272)

333 = 2+6+8+12+16+17+272

1 = egypt(2,4,9,11,22,396)

444 = 2+4+9+11+22+396

1 = egypt(5,6,9,10,11,12,15,20,21,22,28,396)

555 = 5+6+9+10+11+12+15+20+21+22+28+396

1 = egypt(2,6,8,10,15,25,600)

666 = 2+6+8+10+15+25+600

1 = egypt(4,5,8,12,14,18,20,21,24,26,28,819)

999 = 4+5+8+12+14+18+20+21+24+26+28+819

Alas, Egyptian fractions like those are attractive but trivial. This isn’t trivial, though:

Prof Greg Martin of the University of British Columbia has found a remarkable Egyptian fraction for 1 with 454 denominators all less than 1000.

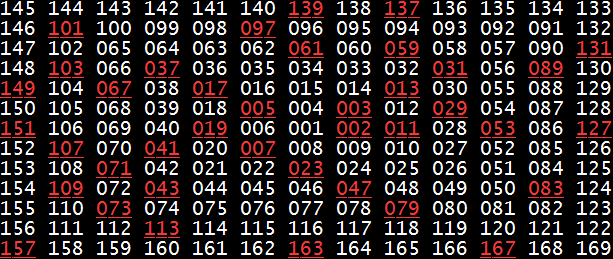

1 = egypt(97, 103, 109, 113, 127, 131, 137, 190, 192, 194, 195, 196, 198, 200, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 225, 228, 230, 231, 234, 235, 238, 240, 244, 245, 248, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256, 259, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 272, 273, 274, 275, 279, 280, 282, 284, 285, 286, 287, 290, 291, 294, 295, 296, 299, 300, 301, 303, 304, 306, 308, 309, 312, 315, 319, 320, 321, 322, 323, 327, 328, 329, 330, 332, 333, 335, 338, 339, 341, 342, 344, 345, 348, 351, 352, 354, 357, 360, 363, 364, 365, 366, 369, 370, 371, 372, 374, 376, 377, 378, 380, 385, 387, 390, 391, 392, 395, 396, 399, 402, 403, 404, 405, 406, 408, 410, 411, 412, 414, 415, 416, 418, 420, 423, 424, 425, 426, 427, 428, 429, 430, 432, 434, 435, 437, 438, 440, 442, 445, 448, 450, 451, 452, 455, 456, 459, 460, 462, 464, 465, 468, 469, 470, 472, 473, 474, 475, 476, 477, 480, 481, 483, 484, 485, 486, 488, 490, 492, 493, 494, 495, 496, 497, 498, 504, 505, 506, 507, 508, 510, 511, 513, 515, 516, 517, 520, 522, 524, 525, 527, 528, 530, 531, 532, 533, 536, 539, 540, 546, 548, 549, 550, 551, 552, 553, 555, 558, 559, 560, 561, 564, 567, 568, 570, 572, 574, 575, 576, 580, 581, 582, 583, 584, 585, 588, 589, 590, 594, 595, 598, 603, 605, 608, 609, 610, 611, 612, 616, 618, 620, 621, 623, 624, 627, 630, 635, 636, 637, 638, 640, 642, 644, 645, 646, 648, 649, 650, 651, 654, 657, 658, 660, 663, 664, 665, 666, 667, 670, 671, 672, 675, 676, 678, 679, 680, 682, 684, 685, 688, 689, 690, 693, 696, 700, 702, 703, 704, 705, 707, 708, 710, 711, 712, 713, 714, 715, 720, 725, 726, 728, 730, 731, 735, 736, 740, 741, 742, 744, 748, 752, 754, 756, 759, 760, 762, 763, 765, 767, 768, 770, 774, 775, 776, 777, 780, 781, 782, 783, 784, 786, 790, 791, 792, 793, 798, 799, 800, 804, 805, 806, 808, 810, 812, 814, 816, 817, 819, 824, 825, 826, 828, 830, 832, 833, 836, 837, 840, 847, 848, 850, 851, 852, 854, 855, 856, 858, 860, 864, 868, 869, 870, 871, 872, 873, 874, 876, 880, 882, 884, 888, 890, 891, 893, 896, 897, 899, 900, 901, 903, 904, 909, 910, 912, 913, 915, 917, 918, 920, 923, 924, 925, 928, 930, 931, 935, 936, 938, 940, 944, 945, 946, 948, 949, 950, 952, 954, 957, 960, 962, 963, 966, 968, 969, 972, 975, 976, 979, 980, 981, 986, 987, 988, 989, 990, 992, 994, 996, 999) — "Egyptian Fractions" by Ron Knott at Surrey University