William Sharp, “Victoria Regia or the Great Water Lily of America (Underside of a Leaf)” (1854), viâ Jeff Thompson

William Sharp, “Victoria Regia or the Great Water Lily of America (Underside of a Leaf)” (1854), viâ Jeff Thompson

Papyrocentric Performativity Presents:

• Sky Story – The Cloud Book: How to Understand the Skies, Richard Hamblyn (David & Charles 2008)

• Wine Words – The Oxford Companion to Wine, ed. Janice Robinson (Oxford University Press 2006)

• Nu Worlds – Numericon, Marianne Freiberger and Rachel Thomas (Quercus Editions 2014)

• Thalassobiblion – Ocean: The Definitive Visual Guide, introduction by Fabien Cousteau (Dorling Kindersley 2014) (posted @ Overlord of the Über-Feral)

Or Read a Review at Random: RaRaR

Joachim Wtewael (sic), Perseus Rescuing Andromeda (1611) (mirrored)

When I first came across this painting in a recent edition of Arthur Cotterell’s Classic Mythology,* it had mutated in two ways: it was mirror-reversed (as above) and Wtewael’s name (pronounced something like “EET-a-vaal”) was printed “WIEWAEL”. At least, I assume the painting was mirror-reversed, because almost all versions on the web have Andromeda on the left, which means that Perseus is holding his sword in his right hand, as you would expect.

I think I prefer the mirrored version, though I don’t know whether that’s because it was the first one I saw. In either version, it is a rich and dramatic painting, full of meaning, seething with symbolism. It’s displayed in the Louvre and if French etymology had been a little different, I could have called it La Conque d’Andromède. Here is the commoner version:

*Mythology of Greece and Rome (Southwater 2003).

The Guardian undertakes a close hermeneutical analysis of some respected figures in the rap community and their complex and challenging lyrical interrogation of issues around neo-liberal capitalism:

In contemporary America, success in overcoming adversity (and often systemic racism) is most often represented in financial terms, and it’s a recurring theme in hip-hop. Consider Kanye West:

I treat the cash the way the government treats AIDS

I won’t be satisfied til all my niggas get it, get it?Or Dr Dre:

Get your money right

Don’t be worried ’bout the next man – make sure your business tight

Get your money right

Go inside the safe, grab your stash that you copped tonight

Get your money right

Be an international player, don’t be scared to catch those red eye flights

You better get your money right

Cause when you out there on the streets, you gotta get it – get itOr even TI himself:

Regardless what haters say I’m as real as they come

I’m chasin that paper baby however it come

I’m singin a song and movin yay by the ton

I bet you never seen a nigga gettin money so young.

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

The Art Book, Phaidon (Second edition 2012)

An A to Z of artists, mostly painters, occasionally sculptors, installers and performers, with a few photographers and video-makers too. You can trace the development, culmination and corruption of high art all the way from Giotto and Fra Angelico through Van Eyck and Caravaggio to Auerbach and Twombly. But the modernist dreck heightens the power of the pre-modernist delights. A few pages after Pieter Claesz’s remarkable A Vanitas Still Life of 1645 there’s Joseph Cornell’s “Untitled” of 1950. One is a skull, watch and overturned glass, skilfully lit, minutely detailed, richly symbolic; the other is a wooden box containing a “frugal assortment of stamps, newspaper cuttings and other objects with no particular relevance to each other”. From the sublime to the slapdash. Over the page from Eleazar Lissitzky’s Composition of 1941 there’s Stefan Lochner’s The Virgin and Child in a Rose Arbour of 1442. One is like a child’s doodle, the other like a jewel. From the slapdash to the sublime.

And so it goes on throughout the book, with beautiful art by great artists following or preceding ugly art by poseurs and charlatans. But some of the modern art is attractive or interesting, like Bridget Riley’s eye-alive Cataract 3 (1961) and Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God (2006). Riley and Hirst aren’t great and Hirst at least is more like an entrepreneur than an artist, but their art here is something that rewards the eye. So is Riley’s art elsewhere, as newcomers to her work might guess from the single example here. That is one of the purposes of a guide like this: to invite – or discourage – further investigation. I vaguely remember seeing the beautiful still-life of a boiled lobster, drinking horn and peeled lemon on page 283 before, but I wouldn’t have recognized the name of the Dutch artist: Willem Kalf (1619-93).

Willem Kalf, Still Life (c. 1653)

Finding Grimshaw here made a good guide even better. The short texts above each art-work pack in a surprising amount of information and anecdote too. What you learn from the texts raises some interesting questions. For example: Why has one small nation contributed so much to the world’s treasury of art? From Van Eyck to Van Gogh by way of Hieronymus Bosch and Jan Vermeer, Holland is comparable to Italy in its importance. But only in painting, not sculpture or architecture. There aren’t just patterns of pigment, texture and geometry in this book: there are patterns of DNA, culture and evolution too. Brilliant, beautiful and banal; skilful, subtle and slapdash: The Art Book has all that and more. It puts jewels inside your skull.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• Ai Wei to Hell — How to Read Contemporary Art, Michael Wilson

• Eyck’s Eyes — Van Eyck, Simone Ferrari

• Face Paint — A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, Laura Cumming

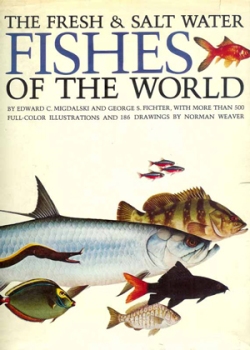

The Fresh and Salt Water Fishes of the World, Edward C. Migdalski and George S. Fichter, illustrated by Norman Weaver (1977)

The Fresh and Salt Water Fishes of the World, Edward C. Migdalski and George S. Fichter, illustrated by Norman Weaver (1977)

A big book with a big subject: fish are the most numerous and varied of the vertebrates, from the bus-sized Rhincodon typus or whale shark, which feeds its vast bulk on plankton, to the little-finger-long Vandellia cirrhosa, the parasitic catfish that can give bathers a nasty surprise by swimming into their “uro-genitary openings” – “the pain is agonizing and the fish can be removed only by surgery”. The book is full of interesting asides like that, but I doubt that readers will read every page carefully. They’ll certainly look at every page carefully, to see Norman Weaver’s gorgeous drawings, which capture both the colour and the shine of fish’s bodies. Another aspect of the enormous variation of fish is not just their differences in size, shape and colouring, but their differences in aesthetic appeal. Some are among the most beautiful of living creatures, others among the most grotesque, like the Lovecraftian horrors that literally dwell in the abyss: inhabitants of the very deep ocean like Chauliodus macouni, the Pacific viperfish, whose teeth are too long and sharp for it to close its mouth.

The crushing pressure and freezing darkness in which these fish live are alien to human beings and so are the appearance and behaviour of the fish. But fish that live in shallow water, like the hammerhead shark and the electric eel, can seem alien too and some of the strangest fish of all, the horizontally flattened rays and mantas, can even fly briefly in the open air. Some of the piscine beauties, on the other hand, like Cheirodon axelrodi, the neon-bodied cardinal tetra, are routinely kept in aquariums, but then so is the very strange Anoptichthys jordani, the blind cavefish. There’s a blind torpedo ray too, Typhlonarke aysoni, “which has no functional eyes and ‘stumps’ along the bottom on its thick, leglike ventral fins”. But the appearance, behaviour and habitat of fish aren’t the only things man finds interesting about them. Some are good eating or offer good sport and the authors often discuss both cuisine and fishing in relation to a particular species or family. That raises the second of the two questions I keep asking myself when I look at this book. The first question is: “Why are some fish so beautiful and some so ugly?” The second is: “Are fish capable of suffering, and if they are, do they suffer much?”

I don’t know if the first question can be answered or is even sensible to ask; the second will, I hope, be answered by science in the negative. It’s not pleasant to think of what a positive answer would mean, because we’ve been hooking and hauling fish from fresh and salt water for countless generations. In the past, it was for food, but when we do it today it’s often for fun. I hope the fun isn’t at fish’s expense in more than the obvious sense: that it deprives them permanently of life or, for those returned to the water, temporarily of peaceful existence. I hope the deprivation is not painful in any strong sense. Either way, fish will continue to die at each other’s fangs and to serve as food for many species of mammal and bird. Nature is red in tooth and claw, after all, but it’s a lot more beside and this is one of the books that will show you how. From luminous sharks to uncannily accurate archerfish, from what men do to fish to what fish do to men: the 315 pages of the large and lavishly illustrated Fishes of the World can offer only a glimpse into a very rich and fascinating world, but a glimpse is dazzling.

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

• Slug is a Drug — Collins Complete Guide to British Coastal Wildlife (2012)

Chrysis ignita, Ruby-tailed wasp

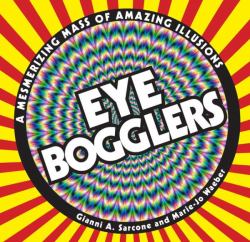

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

A simple book with some complex illusions. It’s aimed at children but scientists have spent decades understanding how certain arrangements of colour and line fool the eye so powerfully. I particularly like the black-and-white tiger set below a patch of blue on page 60. Stare at the blue “for 15 seconds”, then look quickly at a tiny cross set between the tiger’s eyes and the killer turns colour.

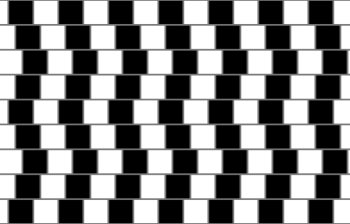

So what’s not there appears to be there, just as, elsewhere, what’s there appears not to be. Straight lines seem curved; large figures seem small; the same colour seems light on the right, dark on the left. There are also some impossible figures, as made famous by M.C. Escher and now studied seriously by geometricians, but the only true art here is a “Face of Fruits” by Arcimboldo. The rest is artful, not art, but it’s interesting to think what Escher might have made of some of the ideas here. Mind is mechanism; mechanism can be fooled. Optical illusions are the most compelling examples, because vision is the most powerful of our senses, but the lesson you learn here is applicable everywhere. This book fools you for fun; others try to fool you for profit. Caveat spectator.

Simple but complex: The café wall illusion

Papyrocentric Performativity Presents:

• Face Paint – A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, Laura Cumming (HarperPress 2009; paperback 2010)

• The Aesthetics of Animals – Life: Extraordinary Animals, Extreme Behaviour, Martha Holmes and Michael Gunton (BBC Books 2009)

• Less Light, More Night – The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artifical Light, Paul Bogard (Fourth Estate 2013)

• The Power of Babel – Clark Ashton Smith, Huysmans, Maupassant

Or Read a Review at Random: RaRaR