The great literary scholar and expert psychoanalyst Dr Miriam B. Stimbers has detected castration, clitoridolatry and communal cannibalism in the novels of Jane Austen. I’m not so ambitious. I merely want to detect a poof in a porker’s poetry. Or rather, I want to detect a poof in the poetry of a peer closely associated with a porker.

The porker is Bill Bunter, the fat, lazy and greedy public schoolboy whose misadventures at Greyfriars School were chronicled, under the pseudonym Frank Richards, by the highly prolific Charles Hamilton (1876-1961). One of Bunter’s schoolfellows was the languid and apparently effete peer Lord Mauleverer, who contributed this poem to The Greyfriars Holiday Annual for 1928:

“The Song of the Slacker”, by Lord Mauleverer

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life was meant for toil and hustle;

It was meant for soothing slumbers,

Which relax both mind and muscle.

Life is lovely! Life is topping!

When you lie beneath the shade,

With the ginger-beer corks popping,

And a glorious spread arrayed.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to put off till to-morrow

Work that should be done today!

In the world’s broad field of battle

All wise soldiers take their ease;

And they lie asleep, like cattle,

Underneath the shady trees.

Trust no Future, trust no Present,

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

The only prospect nice and pleasant

Is that of “forty winks” in bed!

“Life is short!” the bards are bawling,

Let’s enjoy it while we may;

On our study sofas sprawling,

Sleeping sixteen hours a day!

Lives of slackers all remind us

We should also rest our limbs;

And, departing, leave behind us,

“Helpful Hints for Tired Tims!”

Helpful hints, at which another

Will, perhaps, just take a peep;

Some exhausted, born-tired brother––

They will send him off to sleep!

While the hustlers are pursuing

Outdoor sports, on land and lake;

Let us, then, be up and doing––

There are several beds to make. – The Greyfriars Holiday Annual for 1928 (1927), Howard Baker abridged edition 1971

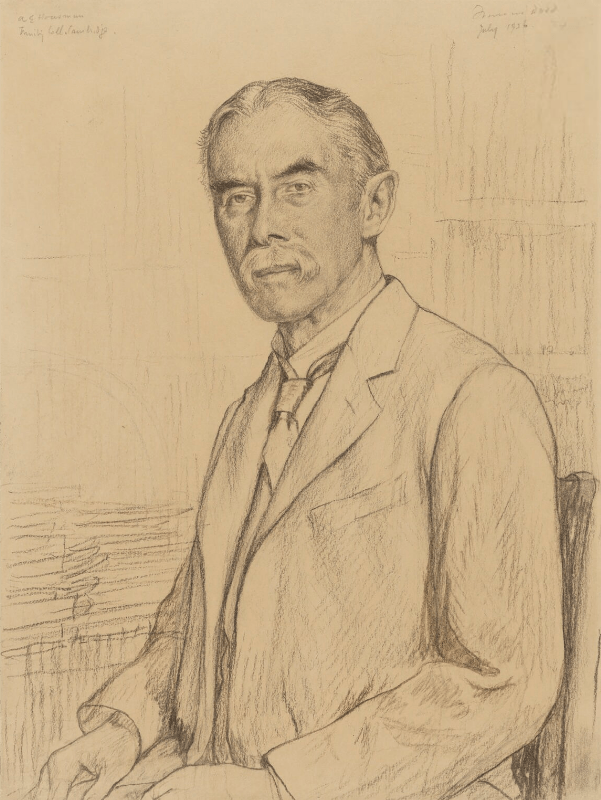

I liked the poem when I first read it, but I didn’t spot the parody as soon as I should. It was unexpected, you see, but then it dawned on me that “The Song of the Slacker” must be a parody of a famous poem by the poof-poet A.E. Housman (1859-1936):

REVEILLE

Wake: the silver dusk returning

Up the beach of darkness brims,

And the ship of sunrise burning

Strands upon the eastern rims.

Wake: the vaulted shadow shatters,

Trampled to the floor it spanned,

And the tent of night in tatters

Straws the sky-pavilioned land.

Up, lad, up, ’tis late for lying;

Hear the drums of morning play;

Hark, the empty highways crying

“Who’ll beyond the hills away?”

Towns and countries woo together,

Forelands beacon, belfries call;

Never lad that trod on leather

Lived to feast his heart with all.

Up, lad: thews that lie and cumber

Sunlit pallets never thrive;

Morns abed and daylight slumber

Were not meant for man alive.

Clay lies still, but blood’s a rover;

Breath’s a ware that will not keep.

Up, lad: when the journey’s over

There’ll be time enough to sleep. – A Shropshire Lad (1896), Poem IV

The meter of the two poems is the same, the period is right, and the sentiments of Housman’s call to energy and effort are turned neatly on their heads in Lord Mauleverer’s call to sleep and slackness. And it’s a clever parody, although it’s a little too long. I’m glad to have come across “The Song of the Slacker”, which the second-best parody of Housman I’ve read. Here’s the best:

What, still alive at twenty-two,

A clean, upstanding chap like you?

Sure, if your throat ’tis hard to slit,

Slit your girl’s, and swing for it.

Like enough, you won’t be glad,

When they come to hang you, lad:

But bacon’s not the only thing

That’s cured by hanging from a string.

So, when the spilt ink of the night

Spreads o’er the blotting-pad of light,

Lads whose job is still to do

Shall whet their knives, and think of you.

• Hugh Kingsmill’s famous parody of A.E. Housman