The bell curve is a shape that appears when you make a graph by counting all possible sums of a range of integers like 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. The smallest sum you can get is 1; the largest is 55 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10. But there’s only one sum of 1 and only one sum of 55. Other sums are more common:

• 10 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4

• 10 = 1 + 2 + 7

• 10 = 1 + 3 + 6

• 10 = 1 + 4 + 5

• 10 = 2 + 3 + 5

• 10 = 2 + 8

• 10 = 3 + 7

• 10 = 4 + 6

• 10 = 10

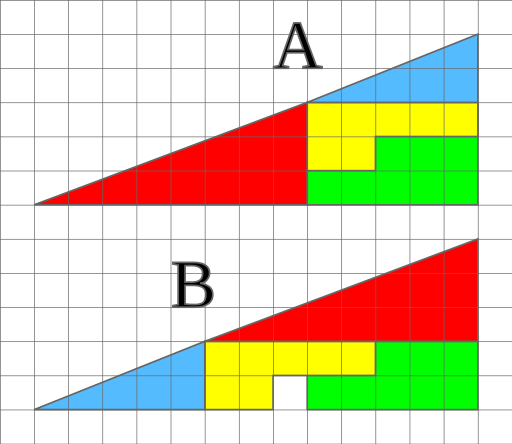

So there are nine sums of 10. If you graph count-sums with a bigger set of consecutive integers from 1, 2, 3…, you get this shape:

Bell curve from sum-counts with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10…

(open in separate window for full-sized image)

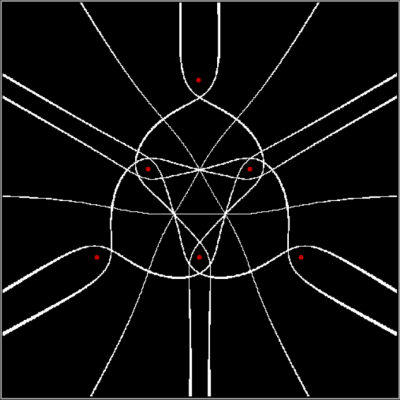

It’s a bell curve. Et c’est une belle curve, a “beautiful curve” in French. But I’ve found what I call bellissime curve — Italian for “most beautiful curves” — by sampling different sets of integers. With the set (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19…), you get what you could call a slightly wrinkled bell curve:

Wrinkled bell-curve from sum-counts with 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19…

(open in separate window for full-sized image)

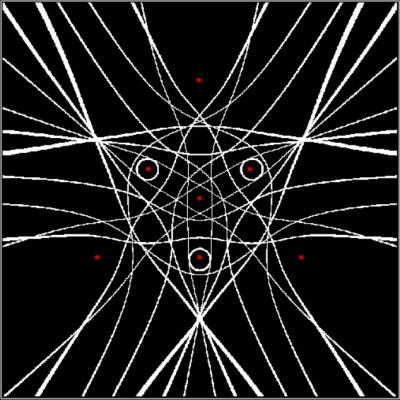

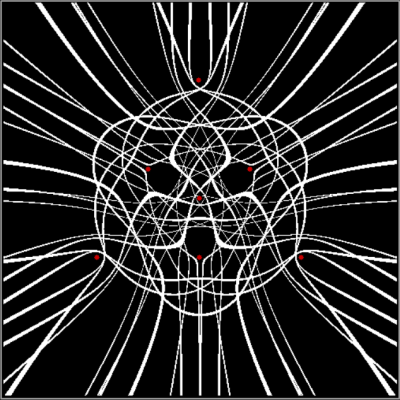

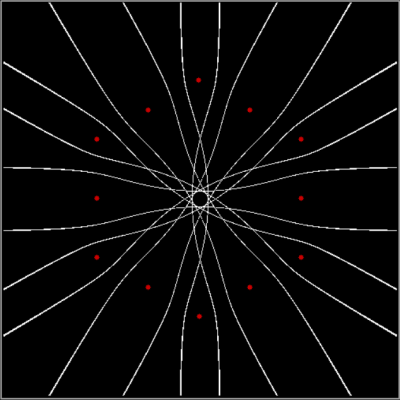

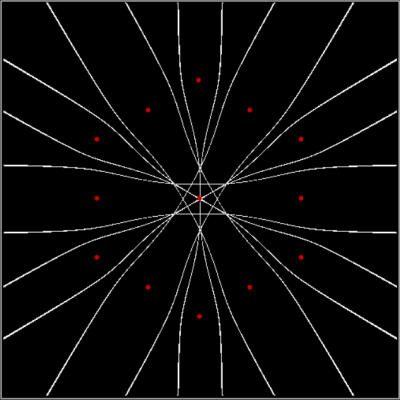

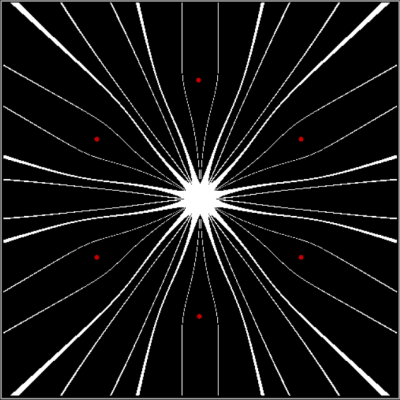

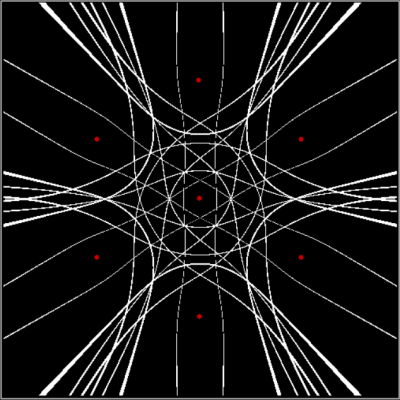

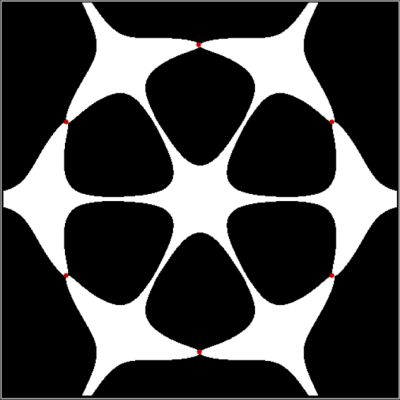

After that, as you leave bigger gaps in the sampled sets, the curves start to overlap and add extra beauty:

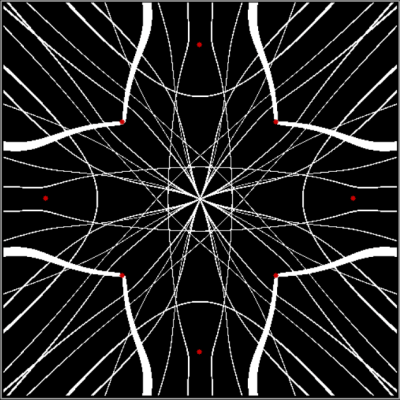

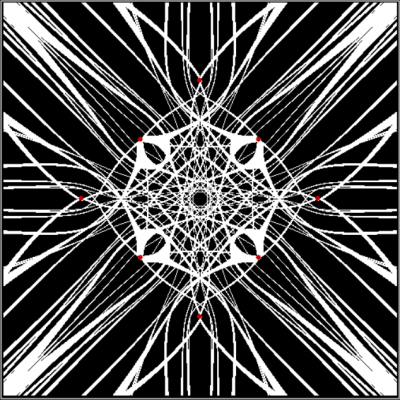

Overlapping bell curves from sum-counts with 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, 28…

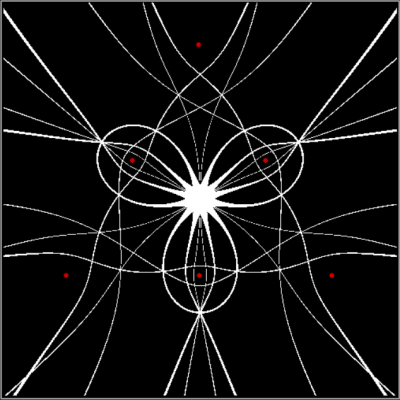

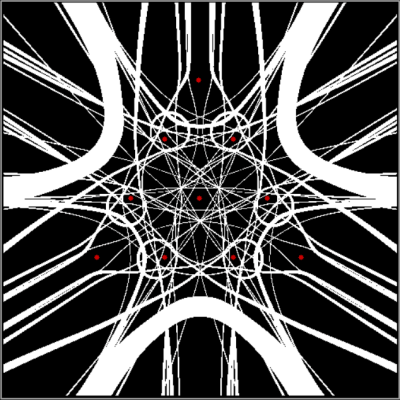

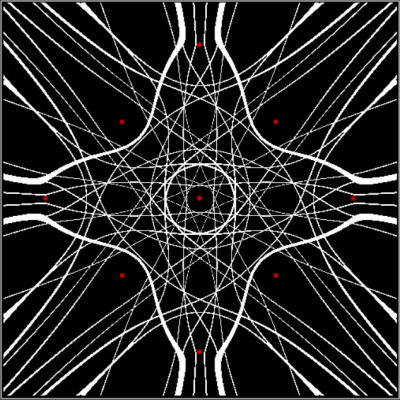

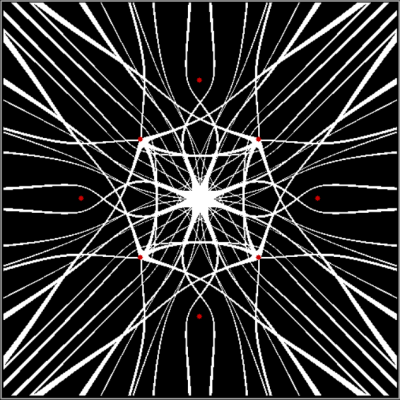

Bellissima curves from sum-counts with 1, 5, 9, 13, 17, 21, 25, 29, 33, 37…

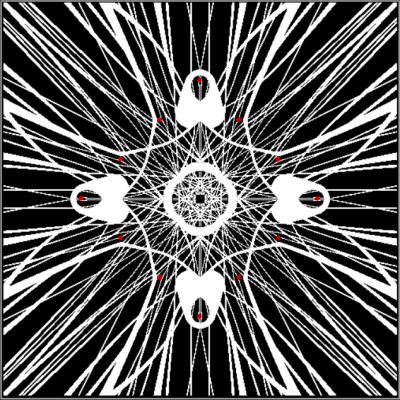

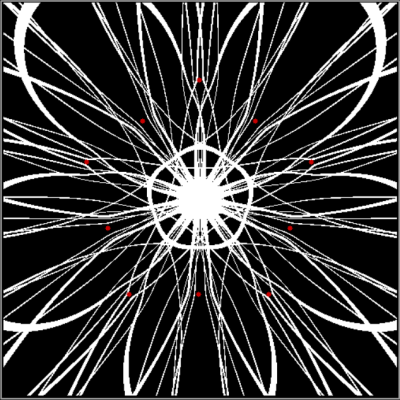

Bellissima curves from sum-counts with 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, 26, 31, 36, 41, 46…

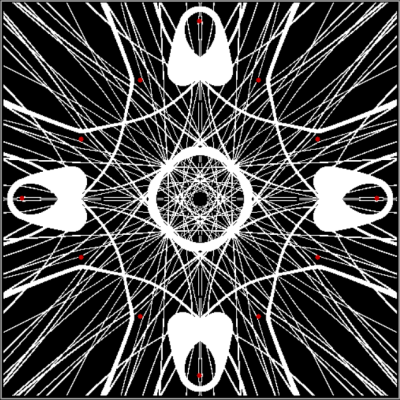

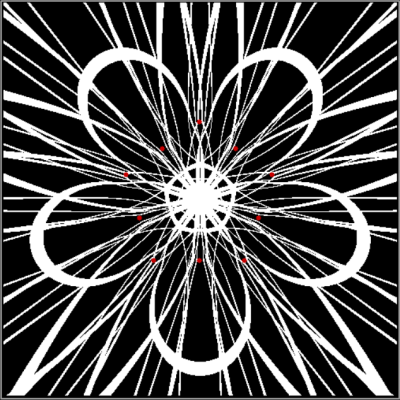

Bellissima curves from sum-counts with 1, 7, 13, 19, 25, 31, 37, 43, 49, 55…

With the set (3, 6, 9, 15, 18, 21…), the bell is back:

Bell curve from sum-counts with 3, 6, 9, 15, 18, 21…

But with (4, 7, 10, 13, 6, 19…), separated by the same distance, you get this:

Bell curve from sum-counts with 4, 7, 10, 13, 6, 19…

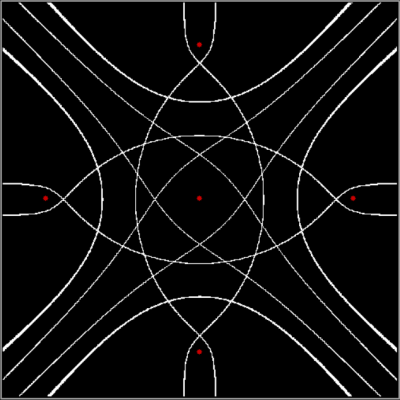

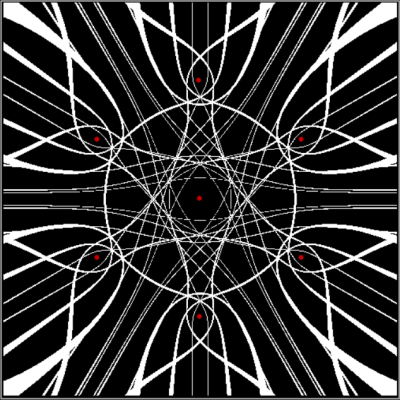

When you sample the Fibonacci numbers, (1, 2, 3, 5, 8…), you get this graph:

Caterpillar curve from sum-counts of Fibonacci numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89…

When you sample a restricted set of Fibonaccis, (1, 3, 8, 21, 55…), you get this, where each vertical line represents a count of one:

Golden gaps from sum-counts of restricted Fibonacci numbers 1, 3, 8, 21, 55, 144…

That restricted Fibonacci graph is strangely attractive, because it has golden gaps (verb sap!).