This is the famous Ulam spiral, in which prime numbers are represented on filled squares on a square spiral:

The Ulam spiral

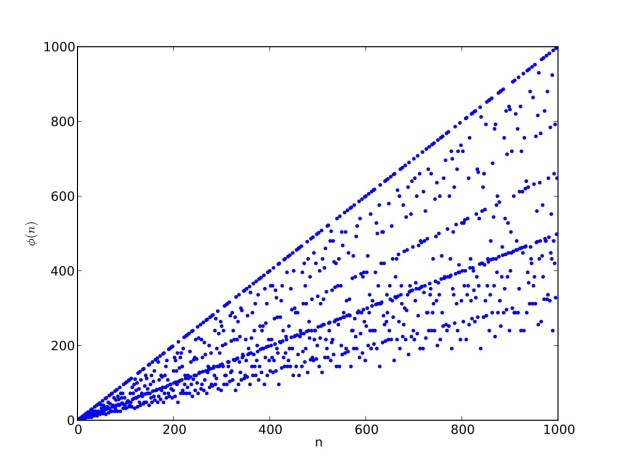

I like the way the spiral sits between chaos and calm. It’s not wholly random and it’s not wholly regular — it’s betwixt and between. You get a similar chaos-and-calm vibe from a graph for a function called Euler phi. And primes are at work there too. Here’s the graph from Wikipedia:

Graph of eulerphi(n) = φ(n) (see Euler’s totient function)

But what is the Euler phi function? For any integer n, eulerphi(n) gives you the count of numbers < n that are relatively prime to n. That is, the count of numbers < n that have no common factors with n other than one. You can see how eulerphi(n) works by considering whether you can simplify the fraction a/b, where a = 1..n-1 and b = n:

φ(6) = 2

1/6 (1)

2/6 → 1/3

3/6 → 1/2

4/6 → 2/3

5/6, ∴ φ(6) = 2

φ(7) = 6

1/7 (1)

2/7 (2)

3/7 (3)

4/7 (4)

5/7 (5)

6/7, ∴ φ(7) = 6

φ(12) = 4

1/12 (1)

2/12 → 1/6

3/12 → 1/4

4/12 → 1/3

5/12 (2)

6/12 → 1/2

7/12 (3)

8/12 → 2/3

9/12 → 3/4

10/12 → 5/6

11/12, ∴ φ(12) = 4

φ(13) = 12

1/13 (1)

2/13 (2)

3/13 (3)

4/13 (4)

5/13 (5)

6/13 (6)

7/13 (7)

8/13 (8)

9/13 (9)

10/13 (10)

11/13 (11)

12/13, ∴ φ(13) = 12

As you can see, eulerphi(n) = n-1 for primes. Now you know what the top line of the Eulerphi graph is. It’s the primes. Here’s a bigger version of the graph:

Graph of eulerphi(n) = φ(n)

Unlike the Ulam spiral, however, the Eulerphi graph is cramped. But it’s easy to stretch it. You can represent φ(n) as a fraction between 0 and 1 like this: phifrac(n) = φ(n) / (n-1). Using phifrac(n), you can create Eulerphi bands, like this:

Eulerphi band, n <= 1781

Eulerphi band, n <= 3561

Eulerphi band, n <= 7121

Eulerphi band, n <= 14241

Or you can create Eulerphi discs, like this:

Eulerphi disc, n <= 1601

Eulerphi disc, n <= 3201

Eulerphi disc, n <= 6401

Eulerphi disc, n <= 12802

Eulerphi disc, n <= 25602

But what is the bottom line of the Eulerphi bands and inner ring of the Eulerphi discs, where φ(n) is smallest relative to n? Well, the top line or outer ring is the primes and the bottom line or inner ring is the primorials (and their multiples). The function primorial(n) is the multiple of the first n primes:

primorial(1) = 2

primorial(2) = 2*3 = 6

primorial(3) = 2*3*5 = 30

primorial(4) = 2*3*5*7 = 210

primorial(5) = 2*3*5*7*11 = 2310

primorial(6) = 2*3*5*7*11*13 = 30030

primorial(7) = 2*3*5*7*11*13*17 = 510510

primorial(8) = 2*3*5*7*11*13*17*19 = 9699690

primorial(9) = 2*3*5*7*11*13*17*19*23 = 223092870

primorial(10) = 2*3*5*7*11*13*17*19*23*29 = 6469693230

Here are the numbers returning record lows for φfrac(n) = φ(n) / (n-1):

φ(4) = 2 (2/3 = 0.666…)

4 = 2^2

φ(6) = 2 (2/5 = 0.4)

6 = 2.3

φ(12) = 4 (4/11 = 0.363636…)

12 = 2^2.3

[…]

φ(30) = 8 (8/29 = 0.275862…)

30 = 2.3.5

φ(60) = 16 (16/59 = 0.27118…)

60 = 2^2.3.5

[…]

φ(210) = 48 (48/209 = 0.229665…)

210 = 2.3.5.7

φ(420) = 96 (96/419 = 0.2291169…)

420 = 2^2.3.5.7

φ(630) = 144 (144/629 = 0.228934…)

630 = 2.3^2.5.7

[…]

φ(2310) = 480 (480/2309 = 0.2078822…)

2310 = 2.3.5.7.11

φ(4620) = 960 (960/4619 = 0.20783719…)

4620 = 2^2.3.5.7.11

[…]

30030 = 2.3.5.7.11.13

φ(60060) = 11520 (11520/60059 = 0.191811385…)

60060 = 2^2.3.5.7.11.13

φ(90090) = 17280 (17280/90089 = 0.1918103209…)

90090 = 2.3^2.5.7.11.13

[…]

φ(510510) = 92160 (92160/510509 = 0.18052571061…)

510510 = 2.3.5.7.11.13.17

φ(1021020) = 184320 (184320/1021019 = 0.18052553…)

1021020 = 2^2.3.5.7.11.13.17

φ(1531530) = 276480 (276480/1531529 = 0.180525474868579…)

1531530 = 2.3^2.5.7.11.13.17

φ(2042040) = 368640 (368640/2042039 = 0.18052544540040616…)

2042040 = 2^3.3.5.7.11.13.17