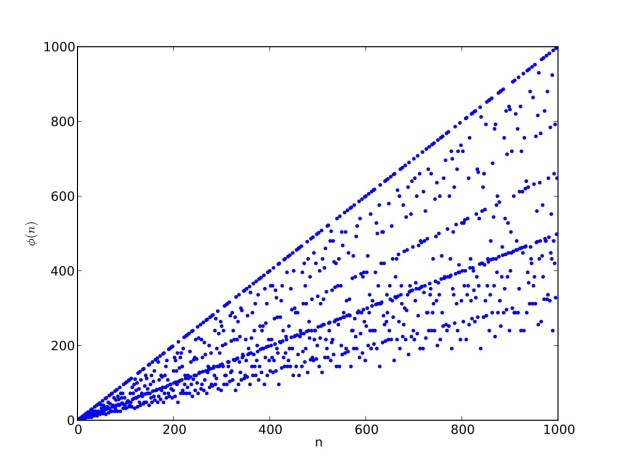

Here’s a second serendipitous fractal:

A serendipitous fractal on a fract-L

It looks like (and is related to) the limestone fractal and I found it similarly serendipitously. This time I was looking at continued fractions, a simple yet subtle and seductive way of representing non-integer numbers like 2/3 and 7/9 (or √2 and π). To generate a continued fraction from a/b < 1, you divide a/b into 1 and take away the integer part. Then you repeat with the remainder until nothing is left (or, as with irrationals like 1/√2 and 1/π, you've calculated long enough for your needs). The integers at each stage are the numbers of the continued fraction. Here is the working for contfrac(2/3), the continued fraction of 2/3:

int(1/(2/3)) = int(3/2) = int(1.5) = 1

3/2 – 1 = 1/2

int(1/(1/2)) = int(2) = 2

2 – 2 = 0contfrac(2/3) = 1, 2

By working backwards with (1, 2), you can use the continued fraction to reconstruct the original number a/b. Start with a/b = 0/1:

1 / (0/1 + 2) = 1 / ((0+2*1)/2) = 1 / (2/1) = 1/2

1 / (1/2 + 1) = 1 / ((1+2*1)/2) = 1 / (3/2) = 2/3

And here’s the working for contfrac(7/9), the continued fraction of 7/9:

int(1/(7/9)) = int(9/7) = int(1.285714…) = 1

9/7 – 1 = 2/7

int(1/(2/7)) = int(7/2) = int(3.5) = 3

7/2 – 3 = 1/2

int(1/(1/2)) = int(2) = 2

2 – 2 = 0contfrac(7/9) = 1, 3, 2

And here’s the reconstruction of 7/9 from its continued fraction, starting again with a/b = 0/1:

1 / (0/1 + 2) = 1 / ((0+2*1)/2) = 1 / (2/1) = 1/2

1 / (1/2 + 3) = 1 / ((1+2*3)/2) = 1 / (7/2) = 2/7

1 / (2/7 + 1) = 1 / ((2+7*1)/7) = 1 / (9/7) = 7/9

From that simple algorithm arise subtle and seductive things. Look at some continued fractions, cf(a/b), for a/b in simplest form (giving only the first few reciprocals, 1/b, because cf(1/b) = b). Interesting patterns appear, e.g. when a/b uses adjacent or nearly adjacent Fibonacci numbers:

cf(1/3) = 3 = cf(0.333333333…)

cf(2/3) = 1,2 = cf(0.666666666…)

cf(1/4) = 4 = cf(0.25)

cf(3/4) = 1,3 = cf(0.75)

cf(1/5) = 5 = cf(0.2)

cf(2/5) = 2,2 = cf(0.4)

cf(3/5) = 1,1,2 = cf(0.6)

cf(4/5) = 1,4 = cf(0.8)

cf(5/6) = 1,5 = cf(0.833333333…)

cf(2/7) = 3,2 = cf(0.285714285…)

cf(3/7) = 2,3 = cf(0.428571428…)

cf(4/7) = 1,1,3 = cf(0.571428571…)

cf(5/7) = 1,2,2 = cf(0.714285714…)

cf(6/7) = 1,6 = cf(0.857142857…)

cf(3/8) = 2,1,2 = cf(0.375)

cf(5/8) = 1,1,1,2 = cf(0.625)

cf(7/8) = 1,7 = cf(0.875)

cf(2/9) = 4,2 = cf(0.222222222…)

cf(4/9) = 2,4 = cf(0.444444444…)

cf(5/9) = 1,1,4 = cf(0.555555555…)

cf(7/9) = 1,3,2 = cf(0.777777777…)

cf(8/9) = 1,8 = cf(0.888888888…)

cf(3/10) = 3,3 = cf(0.3)

cf(7/10) = 1,2,3 = cf(0.7)

cf(9/10) = 1,9 = cf(0.9)

cf(2/11) = 5,2 = cf(0.181818181…)

cf(3/11) = 3,1,2 = cf(0.272727272…)

cf(4/11) = 2,1,3 = cf(0.363636363…)

cf(5/11) = 2,5 = cf(0.454545454…)

cf(6/11) = 1,1,5 = cf(0.545454545…)

cf(7/11) = 1,1,1,3 = cf(0.636363636…)

cf(8/11) = 1,2,1,2 = cf(0.727272727…)

cf(9/11) = 1,4,2 = cf(0.818181818…)

cf(10/11) = 1,10 = cf(0.909090909…)

cf(5/12) = 2,2,2 = cf(0.416666666…)

cf(7/12) = 1,1,2,2 = cf(0.583333333…)

cf(11/12) = 1,11 = cf(0.916666666…)

cf(2/13) = 6,2 = cf(0.153846153…)

cf(3/13) = 4,3 = cf(0.230769230…)

cf(4/13) = 3,4 = cf(0.307692307…)

cf(5/13) = 2,1,1,2 = cf(0.384615384…)

cf(6/13) = 2,6 = cf(0.461538461…)

cf(7/13) = 1,1,6 = cf(0.538461538…)

cf(8/13) = 1,1,1,1,2 = cf(0.615384615…)

cf(9/13) = 1,2,4 = cf(0.692307692…)

cf(10/13) = 1,3,3 = cf(0.769230769…)

cf(11/13) = 1,5,2 = cf(0.846153846…)

cf(12/13) = 1,12 = cf(0.923076923…)

cf(3/14) = 4,1,2 = cf(0.214285714…)

cf(5/14) = 2,1,4 = cf(0.357142857…)

cf(9/14) = 1,1,1,4 = cf(0.642857142…)

cf(11/14) = 1,3,1,2 = cf(0.785714285…)

cf(13/14) = 1,13 = cf(0.928571428…)

cf(2/15) = 7,2 = cf(0.133333333…)

cf(4/15) = 3,1,3 = cf(0.266666666…)

cf(7/15) = 2,7 = cf(0.466666666…)

cf(8/15) = 1,1,7 = cf(0.533333333…)

cf(11/15) = 1,2,1,3 = cf(0.733333333…)

cf(13/15) = 1,6,2 = cf(0.866666666…)

cf(14/15) = 1,14 = cf(0.933333333…)

cf(3/16) = 5,3 = cf(0.1875)

cf(5/16) = 3,5 = cf(0.3125)

cf(7/16) = 2,3,2 = cf(0.4375)

After investigating some of those patterns, I wondered what happened when you reversed the continued fraction cf(a/b) and used those reversed numbers backward (that is, used the numbers of cf(a/b) forward) to generate another and different a/b. And a/b will always be different unless cf(a/b) is a palindrome, like cf(5/12) = 2,2,2 or cf(5/13) = 2,1,1,2 or cf(4/15) = 3,1,3. Note that a continued fraction never ends in 1, so that when reversing, say, cf(5/8) = (1, 1, 1, 2), you need an adjustment from (2, 1, 1, 1) to (2, 1, 1+1) = (2, 1, 2). Here’s a little of what happens when you reverse cf(a1/b1) to generate a2/b2:

cf(1/2) = 2 → 2 = cf(1/2)

1/2 = 0.5 : 0.5 = 1/2

cf(1/3) = 3 → 3 = cf(1/3)

1/3 = 0.333333333 : 0.333333333 = 1/3

cf(2/3) = 1, 2 → 2, 1 → 3 = cf(1/3)

2/3 = 0.666666666 : 0.333333333 = 1/3

cf(3/4) = 1, 3 → 3, 1 → 4 = cf(1/4)

3/4 = 0.75 : 0.25 = 1/4

cf(2/5) = 2, 2 → 2, 2 = cf(2/5)

2/5 = 0.4 : 0.4 = 2/5

cf(3/5) = 1, 1, 2 → 2, 1, 1 → 2, 2 = cf(2/5)

3/5 = 0.6 : 0.4 = 2/5

cf(4/5) = 1, 4 → 4, 1 → 5 = cf(1/5)

4/5 = 0.8 : 0.2 = 1/5

cf(5/6) = 1, 5 → 5, 1 → 6 = cf(1/6)

5/6 = 0.833333333 : 0.166666666 = 1/6

cf(2/7) = 3, 2 → 2, 3 = cf(3/7)

2/7 = 0.285714286 : 0.428571428 = 3/7

cf(3/7) = 2, 3 → 3, 2 = cf(2/7)

3/7 = 0.428571429 : 0.285714286 = 2/7

cf(4/7) = 1, 1, 3 → 3, 1, 1 → 3, 2 = cf(2/7)

4/7 = 0.571428571 : 0.285714286 = 2/7

cf(5/7) = 1, 2, 2 → 2, 2, 1 → 2, 3 = cf(3/7)

5/7 = 0.714285714 : 0.428571429 = 3/7

cf(6/7) = 1, 6 → 6, 1 → 7 = cf(1/7)

6/7 = 0.857142857 : 0.142857143 = 1/7

cf(3/8) = 2, 1, 2 → 2, 1, 2 = cf(3/8)

0.375 : 0.375

cf(5/8) = 1, 1, 1, 2 → 2, 1, 1, 1 → 2, 1, 2 = cf(3/8)

0.625 : 0.375

cf(7/8) = 1, 7 → 7, 1 → 8 = cf(1/8)

0.875 : 0.125

cf(2/9) = 4, 2 → 2, 4 = cf(4/9)

0.222222222 : 0.444444444

cf(4/9) = 2, 4 → 4, 2 = cf(2/9)

0.444444444 : 0.222222222

And if you plot x = a1/b1 and y = (a2/b2 * 2) on a fract-L, that is, a graph whose horizontal and vertical arms represent 0 to 1, you get the fractal right at the beginning:

Fract-L for x = a1/b1 and y = (a2/b2 * 2), where a2/b2 is generated from reversed(cf(a1/b1))

You need to use (a2/b2 * 2) because a2/b2 from reversed(cf(a1/b1)) is always <= 0.5, so using raw a2/b2 generates this graph:

Fract-L for x = a1/b1 and y = a2/b2 (i.e. a2/b2 is unadjusted)

Why is it always true that a2/b2 <= 0.5? For two reasons. First, a/b > 0.5 always generate continued fractions that start with 1, like cf(2/3) = 1, 2 or cf(3/4) = 1, 3 or cf(3/5) = 1, 1, 2. Second, as previously mentioned, no continued fraction ends with 1. Therefore a reversed cf(a1/b1), where the final number, n > 1, moves to the beginning, will never begin with 1 and the a2/b2 generated from reversed(cf(a1/b1)) will always be less than 0.5 (or equal to it in the solitary case of cf(1/2) = 2).

Now let's look at the development of the fractal as a1/b1 uses larger and larger denominators:

Fract-L for x = a1/b1 and y = (a2/b2 * 2) for a1/b1 <= 6/7

Fract-L for for a1/b1 <= 14/15

Fract-L for a1/b1 <= 30/31

Fract-L for a1/b1 <= 62/63

Fract-L for a1/b1 <= 126/127

Fract-L for a1/b1 <= 254/255

Fract-L for a1/b1 <= 357/358

Fract-L for a1/b1 <= 467/468

Animated fract-L for x = a1/b1 and y = (a2/b2 * 2) (animated at ezGif)

The fractal changes subtly when you restrict the b1 of a1/b1 in some way, say using multiples of 2, 3, 4, 5…:

Fract-L for x = a1/b1 and y = (a2/b2 * 2) for b1 = n = 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8…

Fract-L for b1 = 2n = 2, 4, 6, 8, 10…

Fract-L for b1 = 3n = 3, 6, 9, 12, 15…

Fract-L for b1 = 4n

Fract-L for b1 = 5n

Fract-L for b1 = 6n

Animated fract-L for b1 = 1n..12n (animated at ezGif)

Finally, here are fract-Ls when b1 is a triangular, square, hexagonal or octagonal number:

Fract-L for x = a1/b1 and y = (a2/b2 * 2) for triangular(b1) = 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28,…

Fract-L for square(b1) = 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49,…

Fract-L for hexagonal(b1) = 6, 15, 28, 45, 66, 91,…

Fract-L for octagonal(b1) = 8, 21, 40, 65, 96, 133,…

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Back to Drac’ — a parallel pun for a pre-previous fractal

• I Like Gryke — a first look at the limestone fractal

• Lime Time — more on the limestone fractal