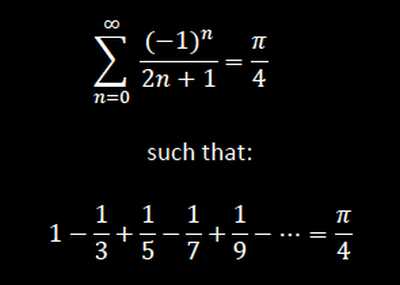

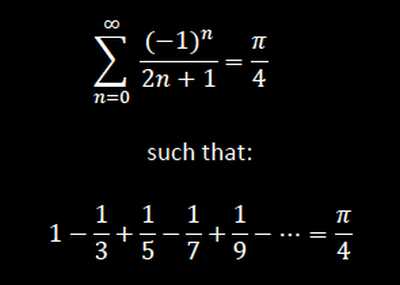

Leibniz's beautiful formula for π using odd reciprocals (image)

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Leibniz formula for π at Wikipedia

Leibniz's beautiful formula for π using odd reciprocals (image)

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Leibniz formula for π at Wikipedia

As any recreational mathematician kno, the Ulam spiral shows the prime numbers on a spiral grid of integers. Here’s a Ulam spiral with 1 represented in blue and 2, 3, 5, 7… as white blocks spiralling anti-clockwise from the right of 1:

The Ulam spiral of prime numbers

Ulam spiral at higher resolution

I like the Ulam spiral and whenever I’m looking at new number sequences I like to Ulamize it, that is, display it on a spiral grid of integers. Sometimes the result looks good, sometimes it doesn’t. But I’ve always wondered something beforehand: will this be the spiral where I see a message appear? That is, will I see a message from Mater Mathematica, Mother Maths, the omniregnant goddess of mathematics? Is there an image or text embedded in some obscure number sequence, revealed when the sequence is Ulamized and proving that there’s divine intelligence and design behind the universe? Maybe the image of a pantocratic cat will appear. Or a text in Latin or Sanskrit or some other suitably century-sanctified language.

That’s what I wonder. I don’t wonder it seriously, of course, but I do wonder it. But until 22nd March 2025 I’d never seen any Ulam-ish spiral that looked remotely like a message. But 22nd May is the day I Ulamed some continued fractions. And I saw something that did look a little like a message. Like text, that is. But I might need to explain continued fractions first. What are they? They’re a fascinating and beautiful way of representing both rational and irrational numbers. The continued fractions for rational numbers look like this in expanded and compact format:

5/3 = 1 + 1/(1 + ½) = 1 + ⅔

5/3 = [1; 1, 2]

19/7 = 2 + 1/(1 + 1/(2 + ½)) = 2 + 4/7

19/7 = [2; 1, 2, 2]

2/3 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/2)

2/3 = [0; 1, 2] (compare 5/3 above)

3/5 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/2))

3/5 = [0; 1, 1, 2]

5/7 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(2 + 1/2))

5/7 = [0; 1, 2, 2] (compare 19/7 above)

13/17 = 0 + 1/(1 + 1/(3 + 1/4))

13/17 = [0; 1, 3, 4]

30/67 = 0 + 1/(2 + 1/(4 + 1/(3 + ½)))

30/67 = [0; 2, 4, 3, 2]

The continued fractions of irrational numbers are different. Most importantly, they never end. For example, here are the infinite continued fractions for φ, √2 and π in expanded and compact format:

φ = 1 + (1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + …)))φ = [1; 1]

√2 = 1 + (1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + …)))

√2 = [1; 2]

π = 3 + 1/(7 + 1/(15 + 1/(1 + 1/(292 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(3 +…))))))))))

π = [3; 7, 15, 1, 292, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 3…]

As you can see, the continued fraction of π doesn’t fall into a predictable pattern like those for φ and √2. But I’ve already gone into continued fractions further than I need for this post, so let’s return to the continued fractions of rationals. I set up an Ulam spiral to show patterns based on the continued fractions for 1/1, ½, ⅓, ⅔, 1/4, 2/4, 3/4, 1/5, 2/5, 3/5, 4/5, 1/6, 2/6, 3/6… (where the fractions are assigned to 1,2,3… and 2/4 = ½, 2/6 = ⅓ etc). For example, if the continued fraction contains a number higher than 5, you get this spiral:

Spiral for continued fractions containing at least number > 5

With tests for higher and higher numbers in the continued fractions, the spirals start to thin and apparent symbols start to appear in the arms of the spirals:

Spiral for contfrac > 10

Spiral for contfrac > 15

Spiral for contfrac > 20

Spiral for contfrac > 25

Spiral for contfrac > 30

Spiral for contfrac > 35

Spiral for contfrac > 40

Spirals for contfrac > 5..40 (animated at EZgif)

Here are some more of these spirals at increasing magnification:

Spiral for contfrac > 23 (#1)

Spiral for contfrac > 23 (#2)

Spiral for contfrac > 23 (#3)

Spiral for contfrac > 13

Spiral for contfrac > 15 (off-center)

Spiral for contfrac > 23 (off-center)

And here are some of the symbols picked out in blue:

Spiral for contfrac > 15 (blue symbols)

Spiral for contfrac > 23 (blue symbols)

But they’re not really symbols, of course. They’re quasi-symbols, artefacts of the Ulamization of a simple test on continued fractions. Still, they’re the closest I’ve got so far to a message from Mater Mathematica.

I was looking at the best rational approximations for π when I was puzzled for a moment or two by the way the precision of digits didn’t always improve:

22/7 →

3.1428571... = 22/7 (precision = 3 digits)

3.1415926... = π

333/106 →

3.141509433... = 333/106 (pr=5)

3.141592653... = π

355/113 →

3.14159292035... = 355/113 (pr=7)

3.14159265358... = π

103993/33102 →

3.14159265301190... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

104348/33215 →

3.14159265392142... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

208341/66317 →

3.14159265346743... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

312689/99532 →

3.14159265361893... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

833719/265381 →

3.1415926535810777... (pr=12)

3.1415926535897932... = π

1146408/364913 →

3.141592653591403... (pr=11)

3.141592653589793... = π

4272943/1360120 →

3.14159265358938917... (pr=13)

3.14159265358979323... = π

5419351/1725033 →

3.14159265358981538... (pr=13)

3.14159265358979323... = π

80143857/25510582 →

3.1415926535897926593... (pr=15)

3.1415926535897932384... = π

165707065/52746197 →

3.14159265358979340254... (pr=16)

3.14159265358979323846... = π

245850922/78256779 →

3.14159265358979316028... (pr=16)

3.14159265358979323846... = π

411557987/131002976 →

3.141592653589793257826... (pr=17)

3.141592653589793238462... = π

1068966896/340262731 →

3.1415926535897932353925... (pr=18)

3.1415926535897932384626... = π

2549491779/811528438 →

3.1415926535897932390140... (pr=18)

3.1415926535897932384626... = π

6167950454/1963319607 →

3.14159265358979323838637... (pr=19)

3.14159265358979323846264... = π

14885392687/4738167652 →

3.141592653589793238493875... (pr=20)

3.141592653589793238462643... = π

But it was my precision that was wrong, of course. I wasn’t thinking about digits precisely enough. One approximation can be closer to π with fewer precise digits than another (e.g. 3.14201… is closer to π than 3.14101…). The same applies in binary, but there the precision tends to increase much more obviously:

22/7 →

3.1428571... = 22/7 in base 10 (pr=3)

3.1415926... = π in base 10

11.0010010010010... = 22/7 in base 2 (pr=9)

11.0010010000111... = π in base 2

333/106 →

3.141509433... = 333/106 in b10 (pr=5)

3.141592653... = π in b10

11.001001000011100111... = 333/106 in b2 (pr=14)

11.001001000011111101... = π in b2

355/113 →

3.14159292035... (pr=7)

3.14159265358... = π

11.00100100001111110110111100... = 355/113 in b2 (pr=22)

11.00100100001111110110101010... = π in b2

103993/33102 →

3.14159265301190... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100001100... (pr=29)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001... = π

104348/33215 →

3.14159265392142... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100010011111... (pr=32)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000... = π

208341/66317 →

3.14159265346743... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100001111... (pr=29)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001... = π

312689/99532 →

3.14159265361893... (pr=10)

3.14159265358979... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100010001010010... (pr=35)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010... = π

833719/265381 →

3.1415926535810777... (pr=12)

3.1415926535897932... = π

11.0010010000111111011010101000100001111... (pr=33)

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000... = π

1146408/364913 →

3.141592653591403... (pr=11)

3.141592653589793... = π

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000111011... (pr=39)

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101... = π

4272943/1360120 →

3.14159265358938917... (pr=13)

3.14159265358979323... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010100110... (pr=41)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010110100... = π

5419351/1725033 →

3.14159265358981538... (pr=13)

3.14159265358979323... = π

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101010010... (pr=45)

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101000110... = π

80143857/25510582 →

3.1415926535897926593... (pr=15)

3.1415926535897932384... = π

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101000101101... (pr=48)

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101000110000... = π

165707065/52746197 →

3.14159265358979340254... (pr=16)

3.14159265358979323846... = π

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100010100... (pr=52)

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001000... = π

245850922/78256779 →

3.14159265358979316028... (pr=16)

3.14159265358979323846... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010110100011000000110... (pr=53)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010110100011000010001... = π

411557987/131002976 →

3.141592653589793257826... (pr=17)

3.141592653589793238462... = π

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001010001... (pr=55)

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001000110... = π

1068966896/340262731 →

3.1415926535897932353925... (pr=18)

3.1415926535897932384626... = π

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001000100110... (pr=58)

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001000110100... = π

2549491779/811528438 →

3.1415926535897932390140... (pr=18)

3.1415926535897932384626... = π

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001000110111010... (pr=61)

11.00100100001111110110101010001000100001011010001100001000110100110... = π

6167950454/1963319607 →

3.14159265358979323838637... (pr=19)

3.14159265358979323846264... = π

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101000110000100011010001101... (pr=63)

11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101000110000100011010011000... = π

14885392687/4738167652 →

3.141592653589793238493875... (pr=20)

3.141592653589793238462643... = π

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010110100011000010001101001110100... (pr=65)

11.001001000011111101101010100010001000010110100011000010001101001100010... = π

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum…

The title of this terato-toxic post is a maximal mash-up (wow) of two well-known toxico-teratic tropes:

• “There are 10 kinds of people in the world. Those who understand binary and those who don’t.”

• Sam Goldwyn’s malapropism: “In two words: im-possible!”

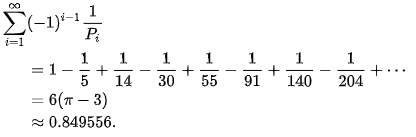

These are the odd numbers:

1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 51, 53, 55, 57, 59...

If you add the odd numbers, 1+3+5+7…, you get the square numbers:

1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100, 121, 144, 169, 196, 225, 256, 289, 324, 361, 400, 441, 484, 529, 576, 625, 676, 729, 784, 841, 900...

And if you add the square numbers, 1+4+9+16…, you get what are called the square pyramidal numbers:

1, 5, 14, 30, 55, 91, 140, 204, 285, 385, 506, 650, 819, 1015, 1240, 1496, 1785, 2109, 2470, 2870, 3311, 3795, 4324, 4900, 5525, 6201, 6930, 7714, 8555, 9455...

There’s not a circle in sight, so you wouldn’t expect to find π amid the pyramids. But it’s there all the same. You can get π from this formula using the square pyramidal numbers:

π from a formula using square pyramidal numbers (Wikipedia)

Here are the approximations getting nearer and near to π:

3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1666666666666666666... = sqpyra2pi(i=1) / 6 + 3

1 = sqpyra(1)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1452380952380952380... = sqpyra2pi(i=3) / 6 + 3

14 = sqpyra(3)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1412548236077647842... = sqpyra2pi(i=8) / 6 + 3

204 = sqpyra(8)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415189855952756236... = sqpyra2pi(i=14) / 6 + 3

1,015 = sqpyra(14)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415990074057163751... = sqpyra2pi(i=33) / 6 + 3

12,529 = sqpyra(33)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415920110950124679... = sqpyra2pi(i=72) / 6 + 3

127,020 = sqpyra(72)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926017980070553... = sqpyra2pi(i=168) / 6 + 3

1,594,684 = sqpyra(168)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926599504002195... = sqpyra2pi(i=339) / 6 + 3

13,043,590 = sqpyra(339)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926530042565359... = sqpyra2pi(i=752) / 6 + 3

142,035,880 = sqpyra(752)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535000384883... = sqpyra2pi(i=1406) / 6 + 3

927,465,791 = sqpyra(1406)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535800054618... = sqpyra2pi(i=2944) / 6 + 3

8,509,683,520 = sqpyra(2944)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535890006043... = sqpyra2pi(i=6806) / 6 + 3

105,111,513,491 = sqpyra(6806)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897000092... = sqpyra2pi(i=13892) / 6 + 3

893,758,038,910 = sqpyra(13892)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897999990... = sqpyra2pi(i=33315) / 6 + 3

12,325,874,793,790 = sqpyra(33315)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897939999... = sqpyra2pi(i=68985) / 6 + 3

109,433,980,000,485 = sqpyra(68985)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897932999... = sqpyra2pi(i=159563) / 6 + 3

1,354,189,390,757,594 = sqpyra(159563)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897932300... = sqpyra2pi(i=309132) / 6 + 3

9,847,199,658,130,890 = sqpyra(309132)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897932389... = sqpyra2pi(i=774865) / 6 + 3

155,080,688,289,901,465 = sqpyra(774865)3.1415926535897932384... = π

3.1415926535897932384... = sqpyra2pi(i=1586190) / 6 + 3

1,330,285,259,163,175,415 = sqpyra(1586190)

As I’ve said before on Overlord of the Über-Feral: squares are boring. As I’ve shown before on Overlord of the Über-Feral: squares are not so boring after all.

Take A000330 at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences:

1, 5, 14, 30, 55, 91, 140, 204, 285, 385, 506, 650, 819, 1015, 1240, 1496, 1785, 2109, 2470, 2870, 3311, 3795, 4324, 4900, 5525, 6201, 6930, 7714, 8555, 9455, 10416, 11440, 12529, 13685, 14910, 16206, 17575, 19019, 20540, 22140, 23821, 25585, 27434, 29370… — A000330 at OEIS

The sequence shows the square pyramidal numbers, formed by summing the squares of integers:

• 1 = 1^2

• 5 = 1^2 + 2^2 = 1 + 4

• 14 = 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 = 1 + 4 + 9

• 30 = 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 + 4^2 = 1 + 4 + 9 + 16[…]

You can see the pyramidality of the square pyramidals when you pile up oranges or cannonballs:

Square pyramid of 91 cannonballs at Rye Castle, East Sussex (Wikipedia)

I looked for palindromes in the square pyramidals. These are the only ones I could find:

1 (k=1)

5 (k=2)

55 (k=5)

1992991 (k=181)

The only ones in base 10, that is. When I looked in base 9 = 3^2, I got a burst of pyramidic palindromes like this:

1 (k=1)

5 (k=2)

33 (k=4) = 30 in base 10 (k=4)

111 (k=6) = 91 in b10 (k=6)

122221 (k=66) = 73810 in b10 (k=60)

123333321 (k=666) = 54406261 in b10 (k=546)

123444444321 (k=6,666) = 39710600020 in b10 (k=4920)

123455555554321 (k=66,666) = 28952950120831 in b10 (k=44286)

123456666666654321 (k=666,666) = 21107018371978630 in b10 (k=398580)

123456777777777654321 (k=6,666,666) = 15387042129569911801 in b10 (k=3587226)

123456788888888887654321 (k=66,666,666) = 11217155797104231969640 in b10 (k=32285040)

The palindromic pattern from 6[…]6 ends with 66,666,666, because 8 is the highest digit in base 9. When you look at the 666,666,666th square pyramidal in base 9, you’ll find it’s not a perfect palindrome:

123456801111111111087654321 (k=666,666,666) = 8177306744945450299267171 in b10 (k=290565366)

But the pattern of pyramidic palindromes is good while it lasts. I can’t find any other base yielding a pattern like that. And base 9 yields another burst of pyramidic palindromes in a related sequence, A000537 at the OEIS:

1, 9, 36, 100, 225, 441, 784, 1296, 2025, 3025, 4356, 6084, 8281, 11025, 14400, 18496, 23409, 29241, 36100, 44100, 53361, 64009, 76176, 90000, 105625, 123201, 142884, 164836, 189225, 216225, 246016, 278784, 314721, 354025, 396900, 443556, 494209, 549081… — A000537 at OEIS

The sequence is what you might call the cubic pyramidal numbers, that is, the sum of the cubes of integers:

• 1 = 1^2

• 9 = 1^2 + 2^3 = 1 + 8

• 36 = 1^3 + 2^3 + 3^3 = 1 + 8 + 27

• 100 = 1^3 + 2^3 + 3^3 + 4^3 = 1 + 8 + 27 + 64[…]

I looked for palindromes there in base 9:

1 (k=1) = 1 (k=1)

121 (k=4) = 100 in base 10 (k=4)

12321 (k=14) = 8281 (k=13)

1234321 (k=44) = 672400 (k=40)

123454321 (k=144) = 54479161 (k=121)

12345654321 (k=444) = 4412944900 (k=364)

1234567654321 (k=1444) = 357449732641 (k=1093)

123456787654321 (k=4444) = 28953439105600 (k=3280)

102012022050220210201 (k=137227) = 12460125198224404009 (k=84022)

But while palindromes are fun, they’re not usually mathematically significant. However, this result using the square pyrmidals is certainly significant:

Previously Pre-Posted…

More posts about how squares aren’t so boring after all:

• Curvous Energy

• Back to Drac #1

• Back to Drac #2

• Square’s Flair

Here is a beautiful and astonishingly simple formula for π created by the French mathematician François Viète (1540-1603):

• 2 / π = √2/2 * √(2 + √2)/2 * √(2 + √(2 + √2))/2…

I can remember testing the formula on a scientific calculator that allowed simple programming. As I pressed the = key and the results began to home in on π, I felt as though I was watching a tall and elegant temple emerge through swirling mist.

The factorial function, n!, is easy to understand. You simply take an integer and multiply it by all integers smaller than it (by convention, 0! = 1):

0! = 1

1! = 1

2! = 2 = 2*1

3! = 6 = 3*2*1

4! = 24 = 4*3*2*1

5! = 120 = 5*4*3*2*1

6! = 720 = 6*120 = 6*5!

7! = 5040

8! = 40320

9! = 362880

10! = 3628800

11! = 39916800

12! = 479001600

13! = 6227020800

14! = 87178291200

15! = 1307674368000

16! = 20922789888000

17! = 355687428096000

18! = 6402373705728000

19! = 121645100408832000

20! = 2432902008176640000

The gamma function, Γ(n), isn’t so easy to understand. It allows you to find the factorials of not just the integers, but everything between the integers, like fractions, square roots, and transcendental numbers like π. Don’t ask me how! And don’t ask me how you get this very beautiful and unexpected result:

Γ(1/2) = √π = 1.77245385091...

But a blog called Mathematical Enchantments can tell you more:

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum

glamour | glamor, n. Originally Scots, introduced into the literary language by Scott. A corrupt form of grammar n.; for the sense compare gramarye n. (and French grimoire ), and for the form glomery n. 1. Magic, enchantment, spell; esp. in the phrase to cast the glamour over one. 2. a. A magical or fictitious beauty attaching to any person or object; a delusive or alluring charm. b. Charm; attractiveness; physical allure, esp. feminine beauty; frequently attributive colloquial (originally U.S.). — Oxford English Dictionary

How radians work (from Wikipedia)

Here’s √2 in base 2:

√2 = 1.01101010000010011110... (base=2)

And in base 3:

√2 = 1.10201122122200121221... (base=3)

And in bases 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10:

√2 = 1.12220021321212133303... (b=4)

√2 = 1.20134202041300003420... (b=5)

√2 = 1.22524531420552332143... (b=6)

√2 = 1.26203454521123261061... (b=7)

√2 = 1.32404746317716746220... (b=8)

√2 = 1.36485805578615303608... (b=9)

√2 = 1.41421356237309504880... (b=10)

And here’s π in the same bases:

π = 11.00100100001111110110... (b=2)

π = 10.01021101222201021100... (b=3)

π = 03.02100333122220202011... (b=4)

π = 03.03232214303343241124... (b=5)

π = 03.05033005141512410523... (b=6)

π = 03.06636514320361341102... (b=7)

π = 03.11037552421026430215... (b=8)

π = 03.12418812407442788645... (b=9)

π = 03.14159265358979323846... (b=10)

Mathematicians know that in all standard bases, the digits of √2 and π go on for ever, without falling into any regular pattern. These numbers aren’t merely irrational but transcedental. But are they also normal? That is, in each base b, do the digits 0 to [b-1] occur with the same frequency 1/b? (In general, a sequence of length l will occur in a normal number with frequency 1/(b^l).) In base 2, are there as many 1s as 0s in the digits of √2 and π? In base 3, are there as many 2s as 1s and 0s? And so on.

It’s a simple question, but so far it’s proved impossible to answer. Another question starts very simple but quickly gets very difficult. Here are the answers so far at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS):

2, 572, 8410815, 59609420837337474 – A049364

The sequence is defined as the “Smallest number that is digitally balanced in all bases 2, 3, … n”. In base 2, the number 2 is 10, which has one 1 and one 0. In bases 2 and 3, 572 = 1000111100 and 210012, respectively. 1000111100 has five 1s and five 0s; 210012 has two 2s, two 1s and two 0s. Here are the numbers of A049364 in the necessary bases:

10 (n=2)

1000111100, 210012 (n=572)

100000000101011010111111, 120211022110200, 200011122333 (n=8410815)

11010011110001100111001111010010010001101011100110000010, 101201112000102222102011202221201100, 3103301213033102101223212002, 1000001111222333324244344 (n=59609420837337474)

But what number, a(6), satisfies the definition for bases 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6? According to the notes at the OEIS, a(6) > 5^434. That means finding a(6) is way beyond the power of present-day computers. But I assume a quantum computer could crack it. And maybe someone will come up with a short-cut or even an algorithm that supplies a(b) for any base b. Either way, I think we’ll get there, π and by.

A roulette is a little wheel or little roller, but it’s much more than a game in a casino. It can also be one of a family of curves created by tracing the path of a point on a rotating circle. Suppose a circle rolls around another circle of the same size. This is the resultant roulette:

The shape is called a cardioid, because it looks like a heart (kardia in Greek). Now here’s a circle with radius r rolling around a circle with radius 2r:

That shape is a nephroid, because it looks like a kidney (nephros in Greek).

This is a circle with radius r rolling around a circle with radius 3r:

The shapes above might be called outer roulettes. But what if a circle rolls inside another circle? Here’s an inner roulette whose radius is three-fifths (0.6) x the radius of its rollee:

The same roulette appears inverted when the inner circle has a radius two-fifths (0.4) x the radius of the rollee:

But what happens when the circle rolling “inside” is larger than the rollee? That is, when the rolling circle is effectively swinging around the rollee, like a bunch of keys being twirled on an index finger? If the rolling radius is 1.5 times larger, the roulette looks like this:

If the rolling radius is 2 times larger, the roulette looks like this:

Here are more outer, inner and over-sized roulettes:

And you can have circles rolling inside circles inside circles:

And here’s another circle-in-a-circle in a circle: