15,527,402,881 = 3534 = 304 + 1204 + 2724 + 3154 — from David Wells’ Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986), entry for “15,527,402,881”

Category Archives: Powers

Power Flip

12 is an interesting number in a lot of ways. Here’s one way I haven’t seen mentioned before:

12 = 3^1 * 2^2

The digits of 12 represent the powers of the primes in its factorization, if primes are represented from right-to-left, like this: …7, 5, 3, 2. But I couldn’t find any more numbers like that in base 10, so I tried a power flip, from right-left to left-right. If the digits from left-to-right represent the primes in the order 2, 3, 5, 7…, then this number is has prime-power digits too:

81312000 = 2^8 * 3^1 * 5^3 * 7^1 * 11^2 * 13^0 * 17^0 * 19^0

Or, more simply, given that n^0 = 1:

81312000 = 2^8 * 3^1 * 5^3 * 7^1 * 11^2

I haven’t found any more left-to-right prime-power digital numbers in base 10, but there are more in other bases. Base 5 yields at least three (I’ve ignored numbers with just two digits in a particular base):

110 in b2 = 2^1 * 3^1 (n=6)

130 in b6 = 2^1 * 3^3 (n=54)

1010 in b2 = 2^1 * 3^0 * 5^1 (n=10)

101 in b3 = 2^1 * 3^0 * 5^1 (n=10)

202 in b7 = 2^2 * 3^0 * 5^2 (n=100)

3020 in b4 = 2^3 * 3^0 * 5^2 (n=200)

330 in b8 = 2^3 * 3^3 (n=216)

13310 in b14 = 2^1 * 3^3 * 5^3 * 7^1 (n=47250)

3032000 in b5 = 2^3 * 3^0 * 5^3 * 7^2 (n=49000)

21302000 in b5 = 2^2 * 3^1 * 5^3 * 7^0 * 11^2 (n=181500)

7810000 in b9 = 2^7 * 3^8 * 5^1 (n=4199040)

81312000 in b10 = 2^8 * 3^1 * 5^3 * 7^1 * 11^2

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum

When I searched for 81312000 at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, I discovered that these are Meertens numbers, defined at A246532 as the “base n Godel encoding of x [namely,] 2^d(1) * 3^d(2) * … * prime(k)^d(k), where d(1)d(2)…d(k) is the base n representation of x.”

Grow Fourth

Write the integers in groups of one, two, three, four… numbers like this:

1, 2,3, 4,5,6, 7,8,9,10, 11,12,13,14,15, 16,17,18,19,20,21, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66…

Now delete every second group:

1, 2,3, 4,5,6, 7,8,9,10, 11,12,13,14,15, 16,17,18,19,20,21, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66…

↓↓↓

1, 4,5,6, 11,12,13,14,15, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66…

The sum of the first n remaining groups equals n^4:

1 = 1 = 1^4

1 + 4+5+6 = 16 = 2^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 = 81 = 3^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 + 22+23+24+25+26+27+28 = 256 = 4^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 + 22+23+24+25+26+27+28 + 37+38+39+40+41+42+43+44+45 = 625 = 5^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 + 22+23+24+25+26+27+28 + 37+38+39+40+41+42+43+44+45 + 56+57+58+59+60+61+62+63+64+65+66 = 1296 = 6^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 + 22+23+24+25+26+27+28 + 37+38+39+40+41+42+43+44+45 + 56+57+58+59+60+61+62+63+64+65+66 + 79+80+81+82+83+84+85+86+87+88+89+90+91 = 2401 = 7^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 + 22+23+24+25+26+27+28 + 37+38+39+40+41+42+43+44+45 + 56+57+58+59+60+61+62+63+64+65+66 + 79+80+81+82+83+84+85+86+87+88+89+90+91 + 106+107+108+109+110+111+112+113+114+115+116+117+118+119+120 = 4096 = 8^4

1 + 4+5+6 + 11+12+13+14+15 + 22+23+24+25+26+27+28 + 37+38+39+40+41+42+43+44+45 + 56+57+58+59+60+61+62+63+64+65+66 + 79+80+81+82+83+84+85+86+87+88+89+90+91 + 106+107+108+109+110+111+112+113+114+115+116+117+118+119+120 + 137+138+139+140+141+142+143+144+145+146+147+148+149+150+151+152+153 = 6561 = 9^4

From David Wells’ Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986), entry for “81”

Pyramidic Palindromes

As I’ve said before on Overlord of the Über-Feral: squares are boring. As I’ve shown before on Overlord of the Über-Feral: squares are not so boring after all.

Take A000330 at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences:

1, 5, 14, 30, 55, 91, 140, 204, 285, 385, 506, 650, 819, 1015, 1240, 1496, 1785, 2109, 2470, 2870, 3311, 3795, 4324, 4900, 5525, 6201, 6930, 7714, 8555, 9455, 10416, 11440, 12529, 13685, 14910, 16206, 17575, 19019, 20540, 22140, 23821, 25585, 27434, 29370… — A000330 at OEIS

The sequence shows the square pyramidal numbers, formed by summing the squares of integers:

• 1 = 1^2

• 5 = 1^2 + 2^2 = 1 + 4

• 14 = 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 = 1 + 4 + 9

• 30 = 1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2 + 4^2 = 1 + 4 + 9 + 16[…]

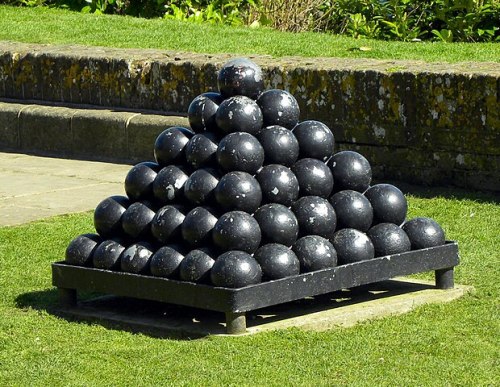

You can see the pyramidality of the square pyramidals when you pile up oranges or cannonballs:

Square pyramid of 91 cannonballs at Rye Castle, East Sussex (Wikipedia)

I looked for palindromes in the square pyramidals. These are the only ones I could find:

1 (k=1)

5 (k=2)

55 (k=5)

1992991 (k=181)

The only ones in base 10, that is. When I looked in base 9 = 3^2, I got a burst of pyramidic palindromes like this:

1 (k=1)

5 (k=2)

33 (k=4) = 30 in base 10 (k=4)

111 (k=6) = 91 in b10 (k=6)

122221 (k=66) = 73810 in b10 (k=60)

123333321 (k=666) = 54406261 in b10 (k=546)

123444444321 (k=6,666) = 39710600020 in b10 (k=4920)

123455555554321 (k=66,666) = 28952950120831 in b10 (k=44286)

123456666666654321 (k=666,666) = 21107018371978630 in b10 (k=398580)

123456777777777654321 (k=6,666,666) = 15387042129569911801 in b10 (k=3587226)

123456788888888887654321 (k=66,666,666) = 11217155797104231969640 in b10 (k=32285040)

The palindromic pattern from 6[…]6 ends with 66,666,666, because 8 is the highest digit in base 9. When you look at the 666,666,666th square pyramidal in base 9, you’ll find it’s not a perfect palindrome:

123456801111111111087654321 (k=666,666,666) = 8177306744945450299267171 in b10 (k=290565366)

But the pattern of pyramidic palindromes is good while it lasts. I can’t find any other base yielding a pattern like that. And base 9 yields another burst of pyramidic palindromes in a related sequence, A000537 at the OEIS:

1, 9, 36, 100, 225, 441, 784, 1296, 2025, 3025, 4356, 6084, 8281, 11025, 14400, 18496, 23409, 29241, 36100, 44100, 53361, 64009, 76176, 90000, 105625, 123201, 142884, 164836, 189225, 216225, 246016, 278784, 314721, 354025, 396900, 443556, 494209, 549081… — A000537 at OEIS

The sequence is what you might call the cubic pyramidal numbers, that is, the sum of the cubes of integers:

• 1 = 1^2

• 9 = 1^2 + 2^3 = 1 + 8

• 36 = 1^3 + 2^3 + 3^3 = 1 + 8 + 27

• 100 = 1^3 + 2^3 + 3^3 + 4^3 = 1 + 8 + 27 + 64[…]

I looked for palindromes there in base 9:

1 (k=1) = 1 (k=1)

121 (k=4) = 100 in base 10 (k=4)

12321 (k=14) = 8281 (k=13)

1234321 (k=44) = 672400 (k=40)

123454321 (k=144) = 54479161 (k=121)

12345654321 (k=444) = 4412944900 (k=364)

1234567654321 (k=1444) = 357449732641 (k=1093)

123456787654321 (k=4444) = 28953439105600 (k=3280)

102012022050220210201 (k=137227) = 12460125198224404009 (k=84022)

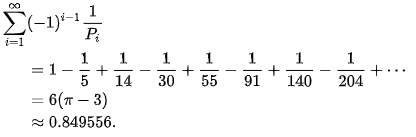

But while palindromes are fun, they’re not usually mathematically significant. However, this result using the square pyrmidals is certainly significant:

Previously Pre-Posted…

More posts about how squares aren’t so boring after all:

• Curvous Energy

• Back to Drac #1

• Back to Drac #2

• Square’s Flair

Square Pairs

Girard knew and Fermat a few years later proved the beautiful theorem that every prime of the form 4n + 1; that is, the primes 5, 13, 17, 29, 37, 41, 53… is the sum of two squares in exactly one way. Primes of the form 4n + 3, such as 3, 7, 11, 19, 23, 31, 43, 47… are never the sum of two squares. — David Wells, The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986), entry for “13”.

Elsewhere other-accessible…

• Fermat’s theorem on sums of two squares

• Pythagorean primes

Bi-Bell Basics

Here’s what you might call a Sisyphean sequence. It struggles upward, then slips back, over and over again:

1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 3, 1, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3, 3, 4, 1, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3, 3, 4, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 1, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3, 3, 4, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 3, 4, 4, 5, 4, 5, 5, 6, 1, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3, 3, 4, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 3, 4, 4, 5, 4, 5, 5, 6, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 3, 4, 4, 5, 4, 5, 5, 6, 3, 4, 4, 5, 4, 5, 5, 6, 4, 5, 5, 6, 5, 6, 6, 7, 1, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3, 3, 4, 2...

The struggle goes on for ever. Every time it reaches a new maximum, it will fall back to 1 at the next step. And in fact 1, 2, 3 and all other integers occur infinitely often in the sequence, because it represents the digit-sums of binary numbers:

1 ← 1

1 = 1+0 ← 10 in binary = 2 in base ten

2 = 1+1 ← 11 = 3

1 = 1+0+0 ← 100 = 4

2 = 1+0+1 ← 101 = 5

2 = 1+1+0 ← 110 = 6

3 = 1+1+1 ← 111 = 7

1 = 1+0+0+0 ← 1000 = 8

2 = 1+0+0+1 ← 1001 = 9

2 = 1+0+1+0 ← 1010 = 10

3 = 1+0+1+1 ← 1011 = 11

2 = 1+1+0+0 ← 1100 = 12

3 = 1+1+0+1 ← 1101 = 13

3 = 1+1+1+0 ← 1110 = 14

4 = 1+1+1+1 ← 1111 = 15

1 = 1+0+0+0+0 ← 10000 = 16

2 = 1+0+0+0+1 ← 10001 = 17

2 = 1+0+0+1+0 ← 10010 = 18

3 = 1+0+0+1+1 ← 10011 = 19

2 = 1+0+1+0+0 ← 10100 = 20

Now here’s a related sequence in which all integers do not occur infinitely often:

1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 6, 4, 5, 6, 7, 7, 8, 9, 10, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9, 10, 11, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12, 13, 14, 15, 6, 7, 8, 9, 9, 10, 11, 12, 10, 11, 12, 13, 13, 14, 15, 16, 11, 12, 13, 14, 14, 15, 16, 17, 15, 16, 17, 18, 18, 19, 20, 21, 7, 8, 9, 10, 10, 11, 12, 13, 11, 12, 13, 14, 14, 15, 16, 17, 12, 13, 14, 15, 15, 16, 17, 18, 16, 17, 18, 19, 19, 20, 21, 22, 13, 14, 15, 16, 16, 17, 18, 19, 17, 18, 19, 20, 20, 21, 22, 23, 18, 19, 20, 21, 21, 22, 23, 24, 22, 23, 24, 25, 25, 26, 27, 28, 8, 9, 10, 11, 11, 12, 13, 14, 12, 13, 14, 15, 15...

The sequence represents the sum of the values of occupied columns in the binary numbers, reading from right to left:

10 in binary = 2 in base ten

21 (column values from right to left)

2*1 + 1*0 = 2

11 = 3

21

2*1 + 1*1 = 3

100 = 4

321 (column values from right to left)

3*1 + 2*0 + 1*0 = 3

101 = 5

321

3*1 + 2*0 + 1*1 = 4

110 = 6

321

3*1 + 2*1 + 1*0 = 5

111 = 7

321

3*1 + 2*1 + 1*1 = 6

1000 = 8

4321

4*1 + 3*0 + 2*0 + 1*0 = 4

1001 = 9

4321

4*1 + 3*0 + 2*0 + 1*1 = 5

1010 = 10

4321

4*1 + 3*0 + 2*1 + 1*0 = 6

1011 = 11

4321

4*1 + 3*0 + 2*1 + 1*1 = 7

1100 = 12

4321

4*1 + 3*1 + 2*0 + 1*0 = 7

1101 = 13

4321

4*1 + 3*1 + 2*0 + 1*1 = 8

1110 = 14

4321

4*1 + 3*1 + 2*1 + 1*0 = 9

1111 = 15

4321

4*1 + 3*1 + 2*1 + 1*1 = 10

10000 = 16

54321

5*1 + 4*0 + 3*0 + 2*0 + 1*0 = 5

In that sequence, although no number occurs infinitely often, some numbers occur more often than others. If you represent the count of sums up to a certain digit-length as a graph, you get a famous shape:

Bell curve formed by the count of column-sums in base 2

Bi-bell curves for 1 to 16 binary digits (animated)

In “Pi in the Bi”, I looked at that way of forming the bell curve and called it the bi-bell curve. Now I want to go further. Suppose that you assign varying values to the columns and try other bases. For example, what happens if you assign the values 2^p + 1 to the columns, reading from right to left, then use base 3 to generate the sums? These are the values of 2^p + 1:

2, 3, 5, 9, 17, 33, 65, 129, 257, 513, 1025...

And here’s an example of how you generate a column-sum in base 3:

2102 in base 3 = 65 in base ten

9532 (column values from right to left)

2*9 + 1*5 + 0*3 + 2*2 = 27

The graphs for these column-sums using base 3 look like this as the digit-length rises. They’re no longer bell-curves (and please note that widths and heights have been normalized so that all graphs fit the same space):

Graph for the count of column-sums in base 3 using 2^p + 1 (digit-length <= 7)

(width and height are normalized)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=8)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=9)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=10)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=11)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=12)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 1 (animated)

Now try base 3 and column-values of 2^p + 2 = 3, 4, 6, 10, 18, 34, 66, 130, 258, 514, 1026…

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 2 (dl<=7)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 2 (dl<=8)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 2 (dl<=9)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 2 (dl<=10)

Graph for base 3 and 2^p + 2 (animated)

Now try base 5 and 2^p + 1 for the columns. The original bell curve has become like a fractal called the blancmange curve:

Graph for base 5 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=7)

Graph for base 5 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=8)

Graph for base 5 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=9)

Graph for base 5 and 2^p + 1 (dl<=10)

Graph for base 5 and 2^p + 1 (animated)

And finally, return to base 2 and try the Fibonacci numbers for the columns:

Graph for base 2 and Fibonacci numbers = 1,1,2,3,5… (dl<=7)

Graph for base 2 and Fibonacci numbers (dl<=9)

Graph for base 2 and Fibonacci numbers (dl<=11)

Graph for base 2 and Fibonacci numbers (dl<=13)

Graph for base 2 and Fibonacci numbers (dl<=15)

Graph for base 2 and Fibonacci numbers (animated)

Previously Pre-Posted…

• Pi in the Bi — bell curves generated by binary digits

Root Pursuit

Roots are hard, powers are easy. For example, the square root of 2, or √2, is the mysterious and never-ending number that is equal to 2 when multiplied by itself:

• √2 = 1·414213562373095048801688724209698078569671875376948073...

It’s hard to calculate √2. But the powers of 2, or 2^p, are the straightforward numbers that you get by multiplying 2 repeatedly by itself. It’s easy to calculate 2^p:

• 2 = 2^1

• 4 = 2^2

• 8 = 2^3

• 16 = 2^4

• 32 = 2^5

• 64 = 2^6

• 128 = 2^7

• 256 = 2^8

• 512 = 2^9

• 1024 = 2^10

• 2048 = 2^11

• 4096 = 2^12

• 8192 = 2^13

• 16384 = 2^14

• 32768 = 2^15

• 65536 = 2^16

• 131072 = 2^17

• 262144 = 2^18

• 524288 = 2^19

• 1048576 = 2^20

[...]

But there is a way to find √2 by finding 2^p, as I discovered after I asked a simple question about 2^p and 3^p. What are the longest runs of matching digits at the beginning of each power?

• 131072 = 2^17

• 129140163 = 3^17

• 1255420347077336152767157884641... = 2^193

• 1214512980685298442335534165687... = 3^193

• 2175541218577478036232553294038... = 2^619

• 2177993962169082260270654106078... = 3^619

• 7524389324549354450012295667238... = 2^2016

• 7524012611682575322123383229826... = 3^2016

There’s no obvious pattern. Then I asked the same question about 2^p and 5^p. And an interesting pattern appeared:

• 32 = 2^5

• 3125 = 5^5

• 316912650057057350374175801344 = 2^98

• 3155443620884047221646914261131... = 5^98

• 3162535207926728411757739792483... = 2^1068

• 3162020133383977882730040274356... = 5^1068

• 3162266908803418110961625404267... = 2^127185

• 3162288411569894029343799063611... = 5^127185

The digits 31622 rang a bell. Isn’t that the start of √10? Yes, it is:

• √10 = 3·1622776601683793319988935444327185337195551393252168268575...

I wrote a fast machine-code program to find even longer runs of matching initial digits. Sure enough, the pattern continued:

• 316227... = 2^2728361

• 316227... = 5^2728361

• 3162277... = 2^15917834

• 3162277... = 5^15917834

• 31622776... = 2^73482154

• 31622776... = 5^73482154

• 3162277660... = 2^961700165

• 3162277660... = 5^961700165

But why are powers of 2 and 5 generating the digits of √10? If you’re good at math, that’s a trivial question about a trivial discovery. Here’s the answer: We use base ten and 10 = 2 * 5, 10^2 = 100 = 2^2 * 5^2 = 4 * 25, 10^3 = 1000 = 2^3 * 5^3 = 8 * 125, and so on. When the initial digits of 2^p and 5^p match, those matching digits must come from the digits of √10. Otherwise the product of 2^p * 5^p would be too large or too small. Here are the records for matching initial digits multiplied by themselves:

• 32 = 2^5

• 3125 = 5^5

• 3^2 = 9

• 316912650057057350374175801344 = 2^98

• 3155443620884047221646914261131... = 5^98

• 31^2 = 961

• 3162535207926728411757739792483... = 2^1068

• 3162020133383977882730040274356... = 5^1068

• 3162^2 = 9998244

• 3162266908803418110961625404267... = 2^127185

• 3162288411569894029343799063611... = 5^127185

• 31622^2 = 999950884

• 316227... = 2^2728361

• 316227... = 5^2728361

• 316227^2 = 99999515529

• 3162277... = 2^15917834

• 3162277... = 5^15917834

• 3162277^2 = 9999995824729

• 31622776... = 2^73482154

• 31622776... = 5^73482154

• 31622776^2 = 999999961946176

• 3162277660... = 2^961700165

• 3162277660... = 5^961700165

• 3162277660^2 = 9999999998935075600

The square of each matching run falls short of 10^p. And so when the digits of 2^p and 5^p stop matching, one power must fall below √10, as it were, and one must rise above:

• 3 162266908803418110961625404267... = 2^127185

• 3·162277660168379331998893544432... = √10

• 3 162288411569894029343799063611... = 5^127185

In this way, 2^p * 5^p = 10^p. And that’s why matching initial digits of 2^p and 5^p generate the digits of √10. The same thing, mutatis mutandis, happens in base 6 with 2^p and 3^p, because 6 = 2 * 3:

• 2.24103122055214532500432040411... = √6 (in base 6)

• 24 = 2^4

• 213 = 3^4

• 225522024 = 2^34 in base 6 = 2^22 in base 10

• 22225525003213 = 3^34 (3^22)

• 2241525132535231233233555114533... = 2^1303 (2^327)

• 2240133444421105112410441102423... = 3^1303 (3^327)

• 2241055222343212030022044325420... = 2^153251 (2^15007)

• 2241003215453455515322105001310... = 3^153251 (3^15007)

• 2241032233315203525544525150530... = 2^233204 (2^20164)

• 2241030204225410320250422435321... = 3^233204 (3^20164)

• 2241031334114245140003252435303... = 2^2110415 (2^102539)

• 2241031103430053425141014505442... = 3^2110415 (3^102539)

And in base 30, where 30 = 2 * 3 * 5, you can find the digits of √30 in three different ways, because 30 = 2 * 15 = 3 * 10 = 5 * 6:

• 5·E9F2LE6BBPBF0F52B7385PE6E5CLN... = √30 (in base 30)

• 55AA4 = 2^M in base 30 = 2^22 in base 10

• 5NO6CQN69C3Q0E1Q7F = F^M = 15^22

• 5E63NMOAO4JPQD6996F3HPLIMLIRL6F... = 2^K6 (2^606)

• 5ECQDMIOCIAIR0DGJ4O4H8EN10AQ2GR... = F^K6 (15^606)

• 5E9DTE7BO41HIQDDO0NB1MFNEE4QJRF... = 2^B14 (2^9934)

• 5E9G5SL7KBNKFLKSG89J9J9NT17KHHO... = F^B14 (15^9934)

[...]

• 5R4C9 = 3^E in base 30 = 3^14 in base 10

• 52CE6A3L3A = A^E = 10^14

• 5E6SOQE5II5A8IRCH9HFBGO7835KL8A = 3^3N (3^113)

• 5EC1BLQHNJLTGD00SLBEDQ73AH465E3... = A^3N (10^113)

• 5E9FI455MQI4KOJM0HSBP3GG6OL9T8P... = 3^EJH (3^13187)

• 5E9EH8N8D9TR1AH48MT7OR3MHAGFNFQ... = A^EJH (10^13187)

[...]

• 5OCNCNRAP = 5^I in base 30 = 5^18 in base 10

• 54NO22GI76 = 6^I (6^18)

• 5EG4RAMD1IGGHQ8QS2QR0S0EH09DK16... = 5^1M7 (5^1567)

• 5E2PG4Q2G63DOBIJ54E4O035Q9TEJGH... = 6^1M7 (6^1567)

• 5E96DB9T6TBIM1FCCK8A8J7IDRCTM71... = 5^F9G (5^13786)

• 5E9NM222PN9Q9TEFTJ94261NRBB8FCH... = 6^F9G (6^13786)

[...]

So that’s √10, √6 and √30. But I said at the beginning that you can find √2 by finding 2^p. How do you do that? By offsetting the powers, as it were. With 2^p and 5^p, you can find the digits of √10. With 2^(p+1) and 5^p, you can find the digits of √2 and √20, because 2^(p+1) * 5^p = 2 * 2^p * 5^p = 2 * 10^p:

• √2 = 1·414213562373095048801688724209698078569671875376948073...

• √20 = 4·472135954999579392818347337462552470881236719223051448...

• 16 = 2^4

• 125 = 5^3

• 140737488355328 = 2^47

• 142108547152020037174224853515625 = 5^46

• 1413... = 2^243

• 1414... = 5^242

• 14141... = 2^6651

• 14142... = 5^6650

• 141421... = 2^35389

• 141420... = 5^35388

• 4472136... = 2^162574

• 4472135... = 5^162573

• 141421359... = 2^3216082

• 141421352... = 5^3216081

• 447213595... = 2^172530387

• 447213595... = 5^172530386

[...]

God Give Me Benf’

In “Wake the Snake”, I looked at the digits of powers of 2 and mentioned a fascinating mathematical phenomenon known as Benford’s law, which governs — in a not-yet-fully-explained way — the leading digits of a wide variety of natural and human statistics, from the lengths of rivers to the votes cast in elections. Benford’s law also governs a lot of mathematical data. It states, for example, that the first digit, d, of a power of 2 in base b (except b = 2, 4, 8, 16…) will occur with the frequency logb(1 + 1/d). In base 10, therefore, Benford’s law states that the digits 1..9 will occur with the following frequencies at the beginning of 2^p:

1: 30.102999%

2: 17.609125%

3: 12.493873%

4: 09.691001%

5: 07.918124%

6: 06.694678%

7: 05.799194%

8: 05.115252%

9: 04.575749%

Here’s a graph of the actual relative frequencies of 1..9 as the leading digit of 2^p (open images in a new window if they appear distorted):

And here’s a graph for the predicted frequencies of 1..9 as the leading digit of 2^p, as calculated by the log(1+1/d) of Benford’s law:

The two graphs agree very well. But Benford’s law applies to more than one leading digit. Here are actual and predicted graphs for the first two leading digits of 2^p, 10..99:

And actual and predicted graphs for the first three leading digits of 2^p, 100..999:

But you can represent the leading digit of 2^p in another way: using an adaptation of the famous Ulam spiral. Suppose powers of 2 are represented as a spiral of squares that begins like this, with 2^0 in the center, 2^1 to the right of center, 2^2 above 2^1, and so on:

←←←⮲

432↑

501↑

6789

If the digits of 2^p start with 1, fill the square in question; if the digits of 2^p don’t start with 1, leave the square empty. When you do this, you get this interesting pattern (the purple square at the very center represents 2^0):

Ulam-like power-spiral for 2^p where 1 is the leading digit

Here’s a higher-resolution power-spiral for 1 as the leading digit:

Power-spiral for 2^p, leading-digit = 1 (higher resolution)

And here, at higher resolution still, are power-spirals for all the possible leading digits of 2^p, 1..9 (some spirals look very similar, so you have to compare those ones carefully):

Power-spiral for 2^p, leading-digit = 1 (very high resolution)

Power-spiral for 2^p, leading-digit = 2

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 3

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 4

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 5

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 6

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 7

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 8

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 9

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 1..9 (animated)

Now try the power-spiral of 2^p, ld = 1, in some other bases:

Power-spiral for 2^p, leading-digit = 1, base = 9

Power-spiral for 2^p, ld = 1, b = 15

You can also try power-spirals for other n^p. Here’s 3^p:

Power-spiral for 3^p, ld = 1, b = 10

Power-spiral for 3^p, ld = 2, b = 10

Power-spiral for 3^p, ld = 1, b = 4

Power-spiral for 3^p, ld = 1, b = 7

Power-spiral for 3^p, ld = 1, b = 18

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• Wake the Snake — an earlier look at the digits of 2^p

Wake the Snake

In my story “Kopfwurmkundalini”, I imagined the square root of 2 as an infinitely long worm or snake whose endlessly varying digit-segments contained all stories ever (and never) written:

• √2 = 1·414213562373095048801688724209698078569671875376948073…

But there’s another way to get all stories ever written from the number 2. You don’t look at the root(s) of 2, but at the powers of 2:

• 2 = 2^1 = 2

• 4 = 2^2 = 2*2

• 8 = 2^3 = 2*2*2

• 16 = 2^4 = 2*2*2*2

• 32 = 2^5 = 2*2*2*2*2

• 64 = 2^6 = 2*2*2*2*2*2

• 128 = 2^7 = 2*2*2*2*2*2*2

• 256 = 2^8 = 2*2*2*2*2*2*2*2

• 512 = 2^9 = 2*2*2*2*2*2*2*2*2

• 1024 = 2^10

• 2048 = 2^11

• 4096 = 2^12

• 8192 = 2^13

• 16384 = 2^14

• 32768 = 2^15

• 65536 = 2^16

• 131072 = 2^17

• 262144 = 2^18

• 524288 = 2^19

• 1048576 = 2^20

• 2097152 = 2^21

• 4194304 = 2^22

• 8388608 = 2^23

• 16777216 = 2^24

• 33554432 = 2^25

• 67108864 = 2^26

• 134217728 = 2^27

• 268435456 = 2^28

• 536870912 = 2^29

• 1073741824 = 2^30

[...]

The powers of 2 are like an ever-lengthening snake swimming across a pool. The snake has an endlessly mutating head and a rhythmically waving tail with a regular but ever-more complex wake. That is, the leading digits of 2^p don’t repeat but the trailing digits do. Look at the single final digit of 2^p, for example:

• 02 = 2^1

• 04 = 2^2

• 08 = 2^3

• 16 = 2^4

• 32 = 2^5

• 64 = 2^6

• 128 = 2^7

• 256 = 2^8

• 512 = 2^9

• 1024 = 2^10

• 2048 = 2^11

• 4096 = 2^12

• 8192 = 2^13

• 16384 = 2^14

• 32768 = 2^15

• 65536 = 2^16

• 131072 = 2^17

• 262144 = 2^18

• 524288 = 2^19

• 1048576 = 2^20

• 2097152 = 2^21

• 4194304 = 2^22

[...]

The final digit of 2^p falls into a loop: 2 → 4 → 8 → 6 → 2 → 4→ 8…

Now try the final two digits of 2^p:

• 02 = 2^1

• 04 = 2^2

• 08 = 2^3

• 16 = 2^4

• 32 = 2^5

• 64 = 2^6

• 128 = 2^7

• 256 = 2^8

• 512 = 2^9

• 1024 = 2^10

• 2048 = 2^11

• 4096 = 2^12

• 8192 = 2^13

• 16384 = 2^14

• 32768 = 2^15

• 65536 = 2^16

• 131072 = 2^17

• 262144 = 2^18

• 524288 = 2^19

• 1048576 = 2^20

• 2097152 = 2^21

• 4194304 = 2^22

• 8388608 = 2^23

• 16777216 = 2^24

• 33554432 = 2^25

• 67108864 = 2^26

• 134217728 = 2^27

• 268435456 = 2^28

• 536870912 = 2^29

• 1073741824 = 2^30

[...]

Now there’s a longer loop: 02 → 04 → 08 → 16 → 32 → 64 → 28 → 56 → 12 → 24 → 48 → 96 → 92 → 84 → 68 → 36 → 72 → 44 → 88 → 76 → 52 → 04 → 08 → 16 → 32 → 64 → 28… Any number of trailing digits, 1 or 2 or one trillion, falls into a loop. It just takes longer as the number of trailing digits increases.

That’s the tail of the snake. At the other end, the head of the snake, the digits don’t fall into a loop (because of the carries from the lower digits). So, while you can get only 2, 4, 8 and 6 as the final digits of 2^p, you can get any digit but 0 as the first digit of 2^p. Indeed, I conjecture (but can’t prove) that not only will all integers eventually appear as the leading digits of 2^p, but they will do so infinitely often. Think of a number and it will appear as the leading digits of 2^p. Let’s try the numbers 1, 12, 123, 1234, 12345…:

• 16 = 2^4

• 128 = 2^7

• 12379400392853802748... = 2^90

• 12340799625835686853... = 2^1545

• 12345257952011458590... = 2^34555

• 12345695478410965346... = 2^63293

• 12345673811591269861... = 2^4869721

• 12345678260232358911... = 2^5194868

• 12345678999199154389... = 2^62759188

But what about the numbers 9, 98, 987, 986, 98765… as leading digits of 2^p? They don’t appear as quickly:

• 9007199254740992 = 2^53

• 98079714615416886934... = 2^186

• 98726397006685494828... = 2^1548

• 98768356967522174395... = 2^21257

• 98765563827287722773... = 2^63296

• 98765426081858871289... = 2^5194871

• 98765430693066680199... = 2^11627034

• 98765432584491513519... = 2^260855656

• 98765432109571471006... = 2^1641098748

Why do fragments of 123456789 appear much sooner than fragments of 987654321? Well, even though all integers occur infinitely often as leading digits of 2^p, some integers occur more often than others, as it were. The leading digits of 2^p are actually governed by a fascinating mathematical phenomenon known as Benford’s law, which states, for example, that the single first digit, d, will occur with the frequency log10(1 + 1/d). Here are the actual frequencies of 1..9 for all powers of 2 up to 2^101000, compared with the estimate by Benford’s law:

1: 30% of leading digits ↔ 30.1% estimated

2: 17.55% ↔ 17.6%

3: 12.45% ↔ 12.49%

4: 09.65% ↔ 9.69%

5: 07.89% ↔ 7.92%

6: 06.67% ↔ 6.69%

7: 05.77% ↔ 5.79%

8: 05.09% ↔ 5.11%

9: 04.56% ↔ 4.57%

Because (inter alia) 1 appears as the first digit of 2^p far more often than 9 does, the fragments of 123456789 appear faster than the fragments of 987654321. Mutatis mutandis, the same applies in all other bases (apart from bases that are powers of 2, where there’s a single leading digit, 1, 2, 4, 8…, followed by 0s). But although a number like 123456789 occurs much frequently than 987654321 in 2^p expressed in base 10 (and higher), both integers occur infinitely often.

As do all other integers. And because stories can be expressed as numbers, all stories ever (and never) written appear in the powers of 2. Infinitely often. You’ll just have to trim the tail of the story-snake.

Weight-Botchers

Suppose you have a balance scale and four weights of 1 unit, 2 units, 4 units and 8 units. How many different weights can you match? If you know binary arithmetic, it’s easy to see that you can match any weight up to fifteen units inclusive. With the object in the left-hand pan of the scale and the weights in the right-hand pan, these are the matches:

01 = 1

02 = 2

03 = 2+1

04 = 4

05 = 4+1

06 = 4+2

07 = 4+2+1

08 = 8

09 = 8+1

10 = 8+2

11 = 8+2+1

12 = 8+4

13 = 8+4+1

14 = 8+4+2

15 = 8+4+2+1

The weights that sum to n match the 1s in the digits of n in binary.

01 = 0001 in binary

02 = 0010 = 2

03 = 0011 = 2+1

04 = 0100 = 4

05 = 0101 = 4+1

06 = 0110 = 4+2

07 = 0111 = 4+2+1

08 = 1000 = 8

09 = 1001 = 8+1

10 = 1010 = 8+2

11 = 1011 = 8+2+1

12 = 1100 = 8+4

13 = 1101 = 8+4+1

14 = 1110 = 8+4+2

15 = 1111 = 8+4+2+1

But there’s another set of four weights that will match anything from 1 unit to 40 units. Instead of using powers of 2, you use powers of 3: 1, 3, 9, 27. But how would you match an object weighing 2 units using these weights? Simple. You put the object in the left-hand scale, the 3-weight in the right-hand scale, and then add the 1-weight to the left-hand scale. In other words, 2 = 3-1. Similarly, 5 = 9-3-1, 6 = 9-3 and 7 = 9-3+1. When the power of 3 is positive, it’s in the right-hand pan; when it’s negative, it’s in the left-hand pan.

This system is actually based on base 3 or ternary, which uses three digits, 0, 1 and 2. However, the relationship between ternary numbers and the sums of positive and negative powers of 3 is more complicated than the relationship between binary numbers and sums of purely positive powers of 2. See if you can work out how to derive the sums in the middle from the ternary numbers on the right:

01 = 1 = 1 in ternary

02 = 3-1 = 2

03 = 3 = 10

04 = 3+1 = 11

05 = 9-3-1 = 12

06 = 9-3 = 20

07 = 9-3+1 = 21

08 = 9-1 = 22

09 = 9 = 100

10 = 9+1 = 101

11 = 9+3-1 = 102

12 = 9+3 = 110

13 = 9+3+1 = 111

14 = 27-9-3-1 = 112

15 = 27-9-3 = 120

16 = 27-9-3+1 = 121

17 = 27-9-1 = 122

18 = 27-9 = 200

19 = 27-9+1 = 201

20 = 27-9+3-1 = 202

21 = 27-9+3 = 210

22 = 27-9+3+1 = 211

23 = 27-3-1 = 212

24 = 27-3 = 220

25 = 27-3+1 = 221

26 = 27-1 = 222

27 = 27 = 1000

28 = 27+1 = 1001

29 = 27+3-1 = 1002

30 = 27+3 = 1010

31 = 27+3+1 = 1011

32 = 27+9-3-1 = 1012

33 = 27+9-3 = 1020

34 = 27+9-3+1 = 1021

35 = 27+9-1 = 1022

36 = 27+9 = 1100

37 = 27+9+1 = 1101

38 = 27+9+3-1 = 1102

39 = 27+9+3 = 1110

40 = 27+9+3+1 = 1111

To begin understanding the sums, consider those ternary numbers containing only 1s and 0s, like n = 1011[3], which equals 31 in decimal. The sum of powers is straightforward, because all of them are positive and they’re easy to work out from the digits of n in ternary: 1011 = 1*3^3 + 0*3^2 + 1*3^1 + 1*3^0 = 27+3+1. Now consider n = 222[3] = 26 in decimal. Just as a decimal number consisting entirely of 9s is always 1 less than a power of 10, so a ternary number consisting entirely of 2s is always 1 less than a power of three:

999 = 1000 - 1 = 10^3 - 1 (decimal)

222 = 1000[3] - 1 (ternary) = 26 = 27-1 = 3^3 - 1 (decimal)

If a ternary number contains only 2s and is d digits long, it will be equal to 3^d – 1. But what about numbers containing a mixture of 2s, 1s and 0s? Well, all ternary numbers containing at least one 2 will have a negative power of 3 in the sum. You can work out the sum by using the following algorithm. Suppose the number is five digits long and the rightmost digit is digit #1 and the leftmost is digit #5:

01. i = 1, sum = 0, extra = 0, posi = true.

02. if posi = false, goto step 07.

03. if digit #i = 0, sum = sum + 0.

04. if digit #i = 1, sum = sum + 3^(i-1).

05. if digit #i = 2, sum = sum - 3^(i-1), extra = 3^5, posi = false.

06. goto step 10.

07. if digit #i = 0, sum = sum + 3^(i-1), extra = 0, posi = true.

08. if digit #i = 1, sum = sum - 3^(i-1).

09. if digit #i = 2, sum = sum + 0.

10. i = i+1. if i <= 5, goto step 2.

11. print sum + extra.

As the number of weights grows, the advantages of base 3 get bigger:

With 02 weights, base 3 reaches 04 and base 2 reaches 3: 04-3 = 1.

With 03 weights, base 3 reaches 13 and base 2 reaches 7: 13-7 = 6.

With 04 weights, 000040 - 0015 = 000025

With 05 weights, 000121 - 0031 = 000090

With 06 weights, 000364 - 0063 = 000301

With 07 weights, 001093 - 0127 = 000966

With 08 weights, 003280 - 0255 = 003025

With 09 weights, 009841 - 0511 = 009330

With 10 weights, 029524 - 1023 = 028501

With 11 weights, 088573 - 2047 = 086526

With 12 weights, 265720 - 4095 = 261625...

But what about base 4, or quaternary? With four weights of 1, 4, 16 and 64, representing powers of 4 from 4^0 to 4^3, you should be able to weigh objects from 1 to 85 units using sums of positive and negative powers. In fact, some weights can’t be matched. As you can see below, if n in base 4 contains a 2, it usually can’t be represented as a sum of positive and negative powers of 4 (one exception is 23 = 2*4 + 3 = 11 in base 10). Certain other numbers are also impossible to represent as that kind of sum:

1 = 1 ← 1

2 has no sum = 2

3 = 4-1 ← 3

4 = 4 ← 10 in base 4

5 = 4+1 ← 11 in base 4

6 has no sum = 12 in base 4

7 has no sum = 13

8 has no sum = 20

9 has no sum = 21

10 has no sum = 22

11 = 16-4-1 ← 23

12 = 16-4 ← 30

13 = 16-4+1 ← 31

14 has no sum = 32

15 = 16-1 ← 33

16 = 16 ← 100

17 = 16+1 ← 101

18 has no sum = 102

19 = 16+4-1 ← 103

20 = 16+4 ← 110

21 = 16+4+1 ← 111

22 has no sum = 112

23 has no sum = 113

24 has no sum = 120

25 has no sum = 121

26 has no sum = 122

27 has no sum = 123

[...]

With a more complicated balance scale, it’s possible to use weights representing powers of base 4 and base 5 (use two pans on each arm of the scale instead of one, placing the extra pan at the midpoint of the arm). But with a standard balance scale, base 3 is the champion. However, there is a way to do slightly better than standard base 3. You do it by botching the weights. Suppose you have four weights of 1, 4, 10 and 28 (representing 1, 3+1, 9+1 and 27+1). There are some weights n you can’t match, but because you can match n-1 and n+1, you know what these unmatchable weights are. Accordingly, while weights of 1, 3, 9 and 27 can measure objects up to 40 units, weights of 1, 4, 10 and 28 can measure objects up to 43 units:

1 = 1 ← 1

2 has no sum = 2

3 = 4-1 ← 10 in base 3

4 = 4 ← 11 in base 3

5 = 4+1 ← 12 in base 3

6 = 10-4 ← 20

7 = 10-4+1 ← 21

8 has no sum = 22

9 = 10-1 ← 100

10 = 10 ← 101

11 = 10+1 ← 102

12 has no sum = 110

13 = 10+4-1 ← 111

14 = 10+4 ← 112

15 = 10+4+1 ← 120

16 has no sum = 121

17 = 28-10-1 ← 122

18 = 28-10 ← 200

19 = 28-10+1 ← 201

20 has no sum = 202

21 = 28-10+4-1 ← 210

22 = 28-10+4 ← 211

23 = 28-4-1 ← 212

24 = 28-4 ← 220

25 = 28-4+1 ← 221

26 has no sum = 222

27 = 28-1 ← 1000

28 = 28 ← 1001

29 = 28+1 ← 1002

30 has no sum = 1010

31 = 28+4-1 ← 1011

32 = 28+4 ← 1012

33 = 28+4+1 ← 1020

34 = 28+10-4 ← 1021

35 = 28+10-4+1 ← 1022

36 has no sum = 1100

37 = 28+10-1 ← 1101

38 = 28+10 ← 1102

39 = 28+10+1 ← 1110

40 = has no sum = 1111*

41 = 28+10+4-1 ← 1112

42 = 28+10+4 ← 1120

43 = 28+10+4+1 ← 1121

*N.B. 40 = 82-28-10-4, i.e. has a sum when another botched weight, 82 = 3^4+1, is used.