St John’s Wort, Hypericum perforatum (image Wikipedia)

St John’s Wort, Hypericum perforatum (image Wikipedia)

0.1666… = 1/6

0.0273972… = 2/73

0.0379746… = 3/79

0.0016181229… = 1/618

0.0027322404… = 2/732 → 1/366

0.0058548009… = 5/854

0.01393354769… = 13/933

0.07598784194… = 75/987 → 25/329

0.08998988877… = 89/989

0.141993957703… = 141/993 → 47/331

0.0005854115443… = 5/8541

0.00129282482223… = 12/9282 → 2/1547

0.00349722279366… = 34/9722 → 17/4861

0.013599274705349… = 135/9927 → 15/1103

0.0000273205382146… = 2/73205

0.0465103… = 4/65 in base 8 = 4/53 in base 10

0.13735223… = 13/73 in b8 = 11/59 in b10

0.0036256353… = 3/625 → 1/207 in b8 = 3/405 → 1/135 in b10

0.01172160236… = 11/721 → 3/233 in b8 = 9/465 → 3/155 in b10

0.01272533117… = 12/725 in b8 = 10/469 in b10

0.03175523464… = 31/755 in b8 = 25/493 in b10

0.06776766655… = 67/767 in b8 = 55/503 in b10

0.251775771755… = 251/775 in b8 = 169/509 in b10

0.0003625152504… = 3/6251 in b8 = 3/3241 in b10

0.00137303402723… = 13/7303 in b8 = 11/3779 in b10

0.00267525714052… = 26/7525 in b8 = 22/3925 in b10

0.035777577356673… = 357/7757 in b8 = 239/4079 in b10

0.3763… = 3/7 in b9 = 3/7 in b10

0.0155187… = 1/55 in b9 = 1/50 in b10

0.0371482… = 3/71 in b9 = 3/64 in b10

0.0474627… = 4/74 in b9 = 4/67 in b10

0.43878684… = 43/87 in b9 = 39/79 in b10

0.07887877766… = 78/878 in b9 = 71/719 in b10

0.01708848667… = 17/0884 → 4/221 in b9 = 16/724 → 4/181 in b10

0.170884866767… = 170/884 → 40/221 in b9 = 144/724 → 36/181 in b10

0.2828… = 2/8 → 1/4 in b11 = 2/8 → 1/4 in b10

0.4986… = 4/9 in b11 = 4/9 in b10

0.54A9A8A6… = 54/A9 in b11 = 59/119 in b10

0.0010A17039… = 1/A17 in b11 = 1/1228 in b10

0.010A170392A… = 10/A17 in b11 = 11/1228 in b10

0.01AA5854872… = 1A/A58 in b11 = 21/1273 in b10

0.027A716A416… = 27/A71 in b11 = 29/1288 in b10

0.032A78032A7… = 32/A78 → 1/34 in b11 = 35/1295 → 1/37 in b10

0.0190AA5A829… = 19/0AA5 → 4/221 in b11 = 20/1325 → 4/265 in b10

0.190AA5A829… = 190/AA5 → 40/221 in b11 = 220/1325 → 44/265 in b10

0.23B7A334… = 23/B7 in b12 = 27/139 in b10

0.075BA597224… = 75/BA5 in b12 = 89/1709 in b10

0.0ABBABAAA99… = AB/BAB in b12 = 131/1715 in b10

0.185BB5B859B4… = 185/BB5 in b12 = 245/1721 in b10

Phiday falls on the 11th, 12th and 23rd of each month, because 11, 12 and 23 represent entries in the famous Fibonacci sequence:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946, 17711, 28657, 46368, 75025, 121393, 196418, 317811, 514229, 832040, 1346269, 2178309, 3524578, 5702887, 9227465, 14930352, 24157817, 39088169, 63245986, 102334155, 165580141, 267914296, 433494437, 701408733, 1134903170, 1836311903, 2971215073, 4807526976, 7778742049, 12586269025, 20365011074, 32951280099, 53316291173, 86267571272, 139583862445, 225851433717, 365435296162, 591286729879, 956722026041, 1548008755920, 2504730781961, 4052739537881, 6557470319842, 10610209857723, 17167680177565, 27777890035288, 44945570212853, 72723460248141, 117669030460994, 190392490709135, 308061521170129, 498454011879264, 806515533049393, 1304969544928657, …

Successive entries in the Fibonacci sequence provide better and better approximations to the golden ratio or φ = 1.61803398874989484820458683…

2 = 2/1

1.5 = 3/2

1.6 = 5/3

1.6 = 8/5

1.625 = 13/8

1.6153846… = 21/13

1.619047619… = 34/21

1.6176470588235294117647… = 55/34

1.618… = 89/55

1.617977528… = 144/89

1.61805… = 233/144

1.618025751… = 377/233

1.618037135… = 610/377

1.618032786… = 987/610

1.618034447… = 1597/987

1.618033813… = 2584/1597

1.618034055… = 4181/2584

1.618033963… = 6765/4181

1.618033998… = 10946/6765

1.618033985… = 17711/10946

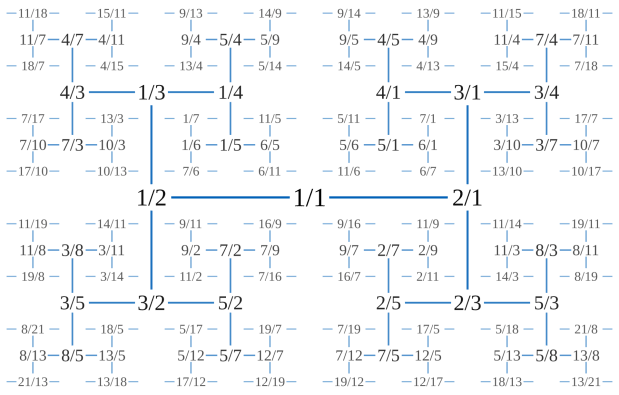

Today is 23rd June, so here’s a Fascinating Fibonacci Fact for Phiday. First, list the rational fractions < 1 in simplified form and mark the Fibonacci fractions:

1/2, 1/3, 2/3, 1/4, 3/4, 1/5, 2/5, 3/5, 4/5, 1/6, 5/6, 1/7, 2/7, 3/7, 4/7, 5/7, 6/7, 1/8, 3/8, 5/8, 7/8, 1/9, 2/9, 4/9, 5/9, 7/9, 8/9, 1/10, 3/10, 7/10, 9/10, 1/11, 2/11, 3/11, 4/11, 5/11, 6/11, 7/11, 8/11, 9/11, 10/11, 1/12, 5/12, 7/12, 11/12, 1/13, 2/13, 3/13, 4/13, 5/13, 6/13, 7/13, 8/13, 9/13, 10/13, 11/13, 12/13, 1/14, 3/14, 5/14, 9/14, 11/14, 13/14, 1/15, 2/15, 4/15, 7/15, 8/15, 11/15, 13/15, 14/15, 1/16, 3/16, 5/16, 7/16, 9/16, 11/16, 13/16, 15/16, 1/17, 2/17, 3/17, 4/17, 5/17, 6/17, 7/17, 8/17, 9/17, 10/17, 11/17, 12/17, 13/17, 14/17, 15/17, 16/17, 1/18, 5/18, 7/18, 11/18, 13/18, 17/18, 1/19, 2/19, 3/19, 4/19, 5/19, 6/19, 7/19, 8/19, 9/19, 10/19, 11/19, 12/19, 13/19, 14/19, 15/19, 16/19, 17/19, 18/19, 1/20, 3/20, 7/20, 9/20, 11/20, 13/20, 17/20, 19/20, 1/21, 2/21, 4/21, 5/21, 8/21, 10/21, 11/21, 13/21, 16/21, 17/21, 19/21, 20/21, 1/22, 3/22, 5/22, 7/22, 9/22, 13/22, 15/22, 17/22, 19/22, 21/22, 1/23, 2/23, 3/23, 4/23, 5/23, 6/23, 7/23, 8/23, 9/23, 10/23, 11/23, 12/23, 13/23, 14/23, 15/23, 16/23, 17/23, 18/23, 19/23, 20/23, 21/23, 22/23…

Next, record the positions in the fraction list of the FibFracs, i.e. pos(fibonacci(i)/fibonacci(i+1)) = pos(fibfrac(i)):

1, 3, 8, 20, 53, 135, 353, 924, 2422, 6311, 16529, 43229, 113066, 296173, 775286, 2029661, 5313844, 13911391, 36419909, 95348490, 249624578, 653521015, 1710943906, 4479312193, 11726939926, 30701521655, 80377560978, 210431191133, 550915866198, 1442316294349, 3776032465954, 9885782372588, 25881314454327, 67758160822605, 177393168080718, 464421339906882, 1215870841639593, …

What do you get when you divide pos(fibfrac(i+1)) by pos(fibfrac(i))?

pos(1/2) = 1

pos(2/3) = 3 (3/1 = 3)

pos(3/5) = 8 (8/3 = 2.6…)

pos(5/8) = 20 (20/8 = 2.5)

pos(8/13) = 53 (53/20 = 2.65)

pos(13/21) = 135 (2.5471698113207…)

pos(21/34) = 353 (2.6148…)

pos(34/55) = 924 (2.617563739376770538243626062…)

pos(55/89) = 2422 (2.621…)

pos(89/144) = 6311 (2.605697770437654830718414533…)

pos(144/233) = 16529 (2.619077800665504674378070037…)

pos(233/377) = 43229 (2.615342730957710690301893642…)

pos(377/610) = 113066 (2.615512734506928219482291980…)

pos(610/987) = 296173 (2.619470044045071020465922559…)

pos(987/1597) = 775286 (2.617679531895209894217231145…)

pos(1597/2584) = 2029661 (2.617951310871084993150914630…)

pos(2584/4181) = 5313844 (2.618094351716863062353762525…)

pos(4181/6765) = 13911391 (2.617952465296309037299551888…)

pos(6765/10946) = 36419909 (2.617991903182075753603647543…)

pos(10946/17711) = 95348490 (2.618032076906068051954770123…)

pos(17711/28657) = 249624578 (2.618023400265699016313735016…)

pos(28657/46368) = 653521015 (2.618015502463863954934758067…)

pos(46368/75025) = 1710943906 (2.618039614227248683043497844…)

pos(75025/121393) = 4479312193 (2.618035680358535377956453004…)

pos(121393/196418) = 11726939926 (2.618022459860278821159630657…)

pos(196418/317811) = 30701521655 (2.618033506501651708043379296…)

pos(317811/514229) = 80377560978 (2.618031831816708695313688353…)

pos(514229/832040) = 210431191133 (2.618034045479393794998913484…)

pos(832040/1346269) = 550915866198 (2.618033302153394031845776103…)

pos(1346269/2178309) = 1442316294349 (2.618033683260502304564996035…)

pos(2178309/3524578) = 3776032465954 (2.618033562227999267671331082…)

pos(3524578/5702887) = 9885782372588 (2.618034262608066669117450079…)

pos(5702887/9227465) = 25881314454327 (2.618034008728793003503058474…)

pos(9227465/14930352) = 67758160822605 (2.618033985181798482654668954…)

pos(14930352/24157817) = 177393168080718 (2.618033989221521810752093192…)

pos(24157817/39088169) = 464421339906882 (2.618033969017113072183685603…)

pos(39088169/63245986) = 1215870841639593 (2.618033964338027806153843993…)

[…]

In other words, pos(fibfrac(i+1)) / pos(fibfrac(i)) → φ^2 = 2.61803398874989484820458683… = φ + 1

Previously Pre-Posted (Please Peruse)

« Si je préfère les chats aux chiens, c’est parce qu’il n’y a pas de chat policier. » — Jean Cocteau

• “If I prefer cats to dogs, it’s because there are no police cats.”

Moz mit Mog (see “Fanny the Cat and Morrissey”) (photo © 2010 by Jake Walters)

Currently listening…

• Cruise The Zygote, T.Q.W. (2024)

• Eisenhaus, Early Lake Gurus (2010)

• Victor Baxter Orchestra, Ivanhoe (1943)

• Youth Dynamo, Night on Skeleton Island (1988)

• Jan in the Box, Pantoscope (1997)

• Chaim Jonas, Unctuous (2008)

• Colder by Weymouth, Steep in the Fen (2017)

• Aëk Gvu, Queen Zoë’s Element (1984)

• New Tomahawks, Boxing Bear (1989)

• Quailhex, Cycle of Song (1976)

• Oligarkhoi, Bittenlamp (2023)

• We the Dynasts, Be the Dynasts (1980)

• Undercore, Atop (and Dazzled) (2019)

• Yellow God, Torrential (1991)

• Intra-47, Holix (2013)

• Ausuttra Land, An Angular History (2021)

• Tuxhray, In a Time of Twenty (1992)

• Yesterway, Everfar (2019)

• Igoud, MgurZadel (2012)

• Candid Bandit, Pinehouse Blues (2022)

Previously pre-posted:

Toxic Turntable #1 • #2 • #3 • #4 • #5 • #6 • #7 • #8 • #9 • #10 • #11 • #12 • #13 • #14 • #15 • #16 • #17 • #18 • #19 • #20 • #21 • #22 • #23 • #24 • #25 • #26 • #27 • #28 •

Sometimes I find fractals. And sometimes fractals find me. Here’s a fractal that found me:

Limestone fractal #1

I call it a limestone fractal or pavement fractal or gryke fractal, because it reminds me of the fissured patterns you see in the limestone pavements of the Yorkshire Dales:

Fissured limestone pavement, Yorkshire Dales (Wikipedia)

The limestone blocks are called clints and the larger fissures between them are called grykes, with kamenitza and karren (from Slavic and German, respectively) for smaller pits and grooves:

Limestone linguistics (Dales Rocks)

Here’s the me-finding fractal again, in a slightly different version:

Limestone fractal #2

How did it find me? Well, I wasn’t looking for fractals, but looking at fractions. Farey fractions and Calkin-Wilf fractions, to be precise. They can both be represented as bifurcating trees, like this:

Calkin-Wilf tree (Wikipedia)

Both trees produce all the irreducible rational fractions — but in a different order. That’s why they create a fractal (rather than a 45° line). By following the same path in both bifurcating trees, I generated parallel sequences of Farey and Calkin-Wilf fractions, then used the Farey fractions to represent x in a 1×1 square and the Calkin-Wilf fractions to represent y (where the Calkin-Wilfs, a/b, were greater than 1, I simply a/b → b/a). When you do that (or use Stern-Brocot fractions instead of the Farey fractions), you get the limestone fractal.

I think it looks better in the second version (which is the one that found me, in fact). For LF #2, I was using standard binary numbers to generate the parallel sequences, so the leftmost digit was always 1 and final step of the tree-search was always in the same direction. Here’s LF #2 as black-on-white rather than white-on-black:

Limestone fractal #2 (black-on-white)

And here is the formation of LF #1 as an animated gif:

Growth of limestone fractal (animated at ezGIF)

And if that’s a me-finding fractal, what about me-found fractals? Here’s one:

The Hourglass Fractal (animated gif optimized at ezGIF)

Hourglass fractal

I can say “I found that fractal” because I was looking for fractals when it appeared on the screen. And re-appeared (and re-re-appeared), because I’ve found it using different methods.

Elsewhere Other-Accessible

• Hour Power — more on the hourglass fractal

Urtica dioica by the German botanist Otto Wilhelm Thomé (1840-1925)

The bell curve is a shape that appears when you make a graph by counting all possible sums of a range of integers like 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. The smallest sum you can get is 1; the largest is 55 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10. But there’s only one sum of 1 and only one sum of 55. Other sums are more common:

• 10 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4

• 10 = 1 + 2 + 7

• 10 = 1 + 3 + 6

• 10 = 1 + 4 + 5

• 10 = 2 + 3 + 5

• 10 = 2 + 8

• 10 = 3 + 7

• 10 = 4 + 6

• 10 = 10

So there are nine sums of 10. If you graph count-sums with a bigger set of consecutive integers from 1, 2, 3…, you get this shape:

Bell curve from sum-counts with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10…

(open in separate window for full-sized image)

It’s a bell curve. Et c’est une belle curve, a “beautiful curve” in French. But I’ve found what I call bellissime curve — Italian for “most beautiful curves” — by sampling different sets of integers. With the set (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19…), you get what you could call a slightly wrinkled bell curve:

Wrinkled bell-curve from sum-counts with 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19…

(open in separate window for full-sized image)

After that, as you leave bigger gaps in the sampled sets, the curves start to overlap and add extra beauty:

Overlapping bell curves from sum-counts with 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, 28…

Bellissima curves from sum-counts with 1, 5, 9, 13, 17, 21, 25, 29, 33, 37…

Bellissima curves from sum-counts with 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, 26, 31, 36, 41, 46…

Bellissima curves from sum-counts with 1, 7, 13, 19, 25, 31, 37, 43, 49, 55…

With the set (3, 6, 9, 15, 18, 21…), the bell is back:

Bell curve from sum-counts with 3, 6, 9, 15, 18, 21…

But with (4, 7, 10, 13, 6, 19…), separated by the same distance, you get this:

Bell curve from sum-counts with 4, 7, 10, 13, 6, 19…

When you sample the Fibonacci numbers, (1, 2, 3, 5, 8…), you get this graph:

Caterpillar curve from sum-counts of Fibonacci numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89…

When you sample a restricted set of Fibonaccis, (1, 3, 8, 21, 55…), you get this, where each vertical line represents a count of one:

Golden gaps from sum-counts of restricted Fibonacci numbers 1, 3, 8, 21, 55, 144…

That restricted Fibonacci graph is strangely attractive, because it has golden gaps (verb sap!).

The 11th, 12th and 23rd day of a month can be called a φ-day (pronounced fy-day). Why so? Because those numbers are consecutive entries in the famous Fibonacci sequence, which offers better and better approximations to a mathematical constant called φ = (√5 + 1) / 2 = 1.6180339887498948…:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946, 17711, …

Each number after the second is the sum of the preceding two (so 11, 12, 23… could be the start of a similar sequence). When you divide fib(i) by fib(i-1), you get these approximations to φ:

2 = 2/1

1.5 = 3/2

1.6 = 5/3

1.6 = 8/5

1.625 = 13/8

1.6153846… = 21/13

1.619047619… = 34/21

1.6176470588235294117647… = 55/34

1.618… = 89/55

1.617977528… = 144/89

1.61805… = 233/144

1.618025751… = 377/233

1.618037135… = 610/377

1.618032786… = 987/610

1.618034447… = 1597/987

1.618033813… = 2584/1597

1.618034055… = 4181/2584

1.618033963… = 6765/4181

1.618033998… = 10946/6765

1.618033985… = 17711/10946

Today is the 23rd and not just a φ-day but a Friday (or φriday). So here’s one of the interesting results I’ve recently found while playing with the Fibonacci sequence. As any recreational mathematician kno, you can also find the Fibonacci sequence — and φ — with this little algorithm:

f = 0

LOOP

f = 1 / (f + 1)

print(f)

goto LOOP

The algorithm returns these values:

1, 1/2, 2/3, 3/5, 5/8, 8/13, 13/21, 21/34, 34/55, 55/89, 89/144, 144/233, 233/377, 377/610, 610/987, 987/1597, 1597/2584, 2584/4181, 4181/6765, 6765/10946, 10946/17711, …

I was playing with that algorithm and got an unexpected result with a simple adaptation of it:

f = 0

LOOP

f = 1 / (3 – f)

print(f)

goto LOOP

The values of f generated by this adapted algorithm are:

1/3, 3/8, 8/21, 21/55, 55/144, 144/377, 377/987, 987/2584, 2584/6765, 6765/17711, 17711/46368, 46368/121393, 121393/317811, 317811/832040, 832040/2178309, 2178309/5702887, 5702887/14930352, 14930352/39088169, 39088169/102334155, 102334155/267914296, …

The numerator and denominator in each fraction are next-but-one Fibonacci numbers, beautifully generated at each step:

3 – 0 = 3 → 1/3

3 – 1/3 = (3*3)/3 – 1/3 = 9/3 – 1/3 = (9-1) / 3 = 8 / 3 → 1/(8/3) = 3/8

3 – 3/8 = (3*8)/3 – 3/8 = 24/8 – 3/8 = (24-3) / 8 = 21/8 → 1/(21/8) = 8/21

3 – 8/21 = (3*21)/21 – 8/21 = 63/21 – 8/21 = (63-8)/21 = 55/21 → 1/(55/21) = 21/55

3 – 21/55 = (3*55)/55 – 21/55 = 165/55 – 21/55 = (165-21)/55 = 144/55 → 1/(144/55) = 55/144

3 – 55/144 = (3*144)/144 – 55/144 = (432-55)/144 = 377/144 → 1/(377/144) = 144/377

3 – 144/377 = (3*377)/377 – 144/377 = (1131-144)/377 = 987/377 → 1/(987/377) = 377/987

[…]

If you reverse numerator and denominator, the limit of the fraction is φ^2 = 2.6180339887498948… = φ+1:

3 = 3/1

2.6 = 8/3

2.625 = 21/8

2.6190476190476190476190476… = 55/21

2.6181818181818181818181818… = 144/55

2.6180555555555555555555555… = 377/144

2.6180371352785145888594164… = 987/377

2.6180344478216818642350557… = 2584/987

2.6180340557275541795665634… = 6765/2584

2.6180339985218033998521803… = 17711/6765

2.6180339901755970865563773… = 46368/17711

2.6180339889579020013802622… = 121393/46368

2.6180339887802426828565073… = 317811/121393

2.6180339887543225376088304… = 832040/317811

2.6180339887505408393827219… = 2178309/832040

2.6180339887499890970472967… = 5702887/2178309

2.6180339887499085989254214… = 14930352/5702887

2.6180339887498968544077192… = 39088169/14930352

2.6180339887498951409056791… = 102334155/39088169

2.6180339887498948909091006… = 267914296/102334155