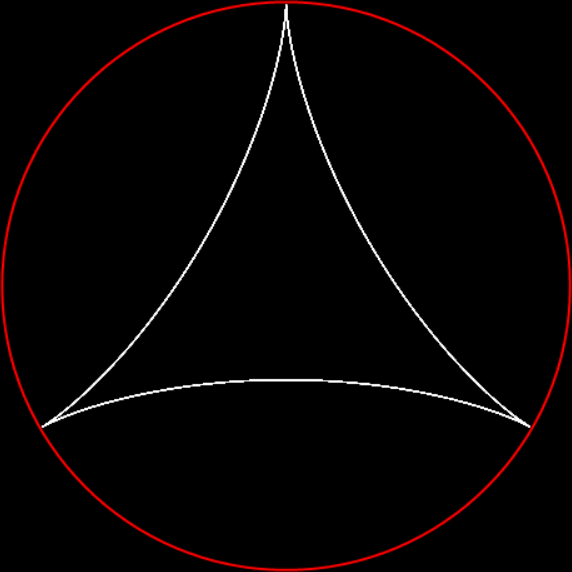

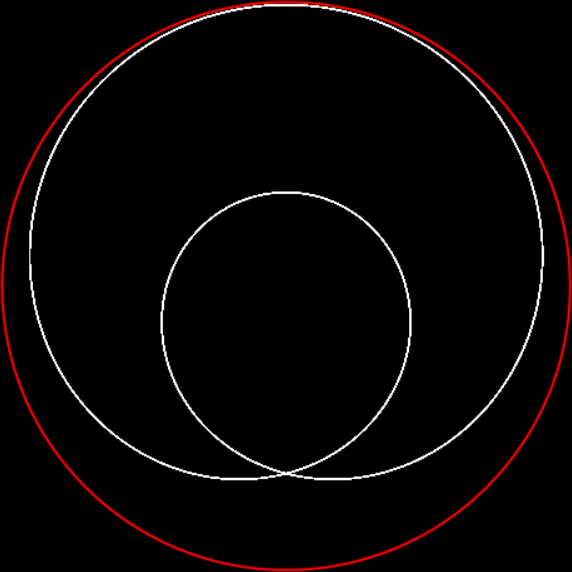

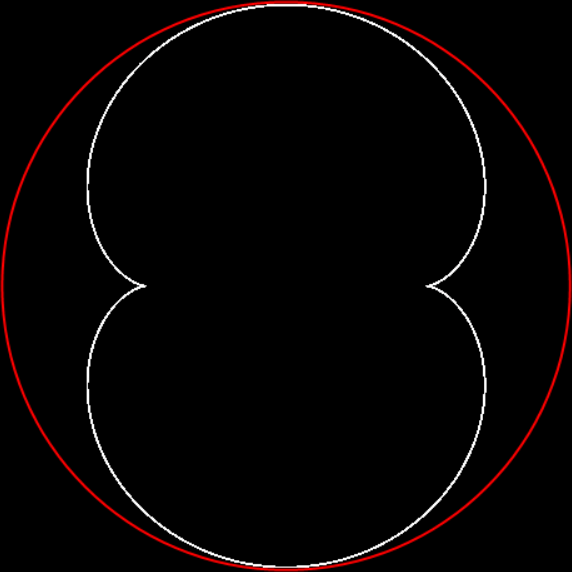

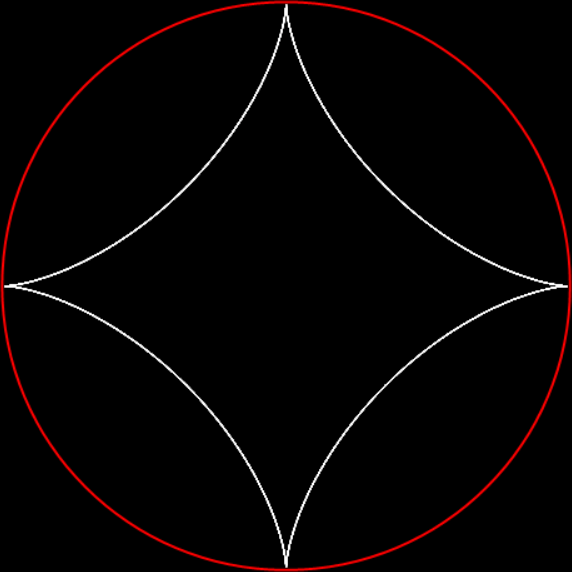

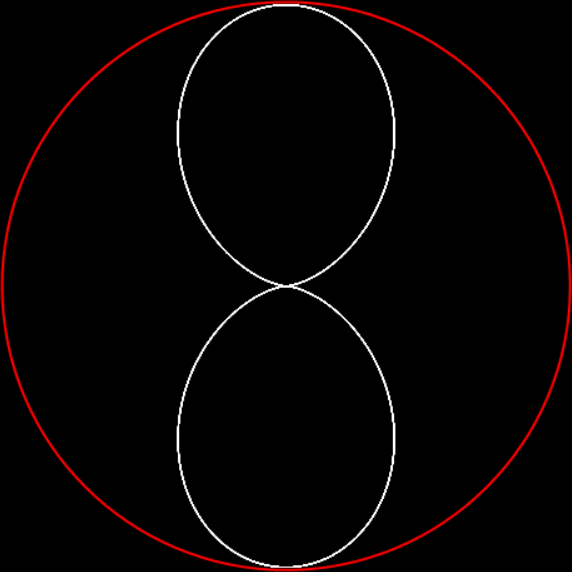

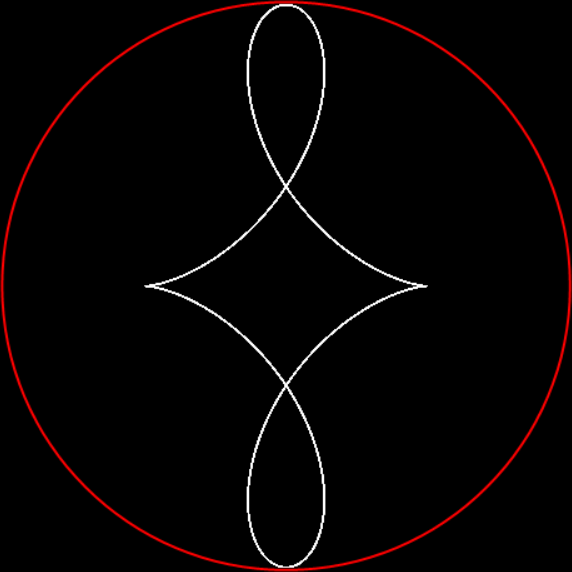

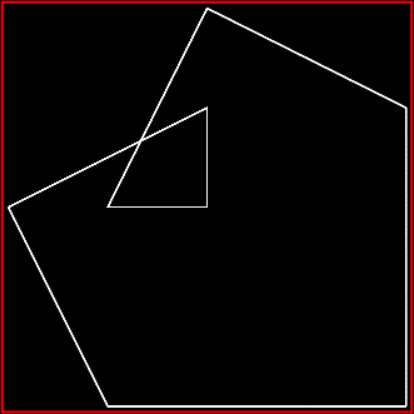

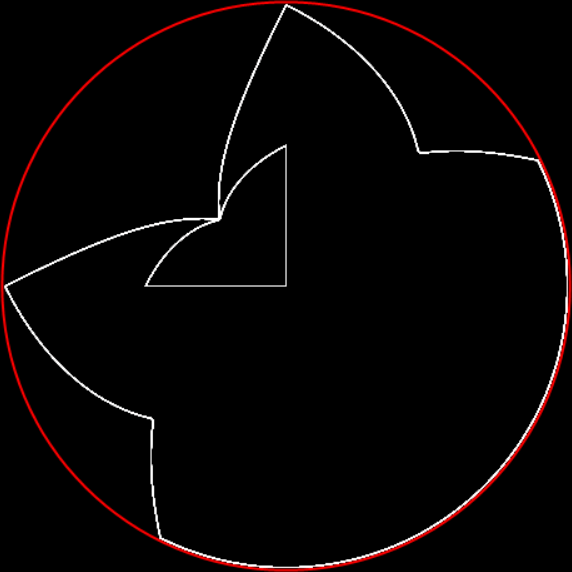

In “Scaffscapes”, I looked at these three fractals and described how they were in a sense the same fractal, even though they looked very different:

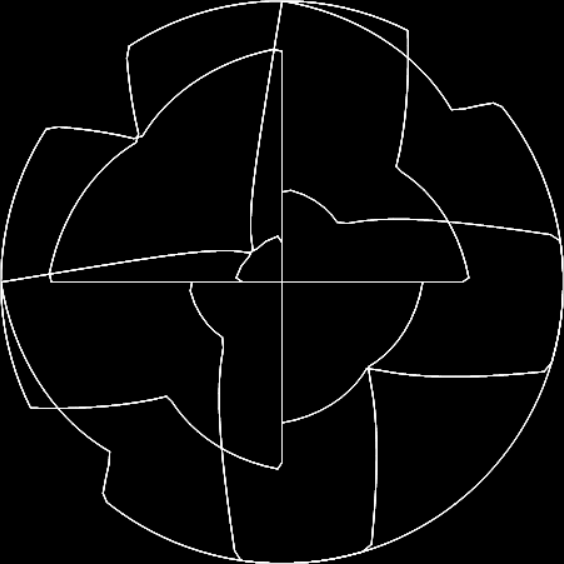

Fractal #1

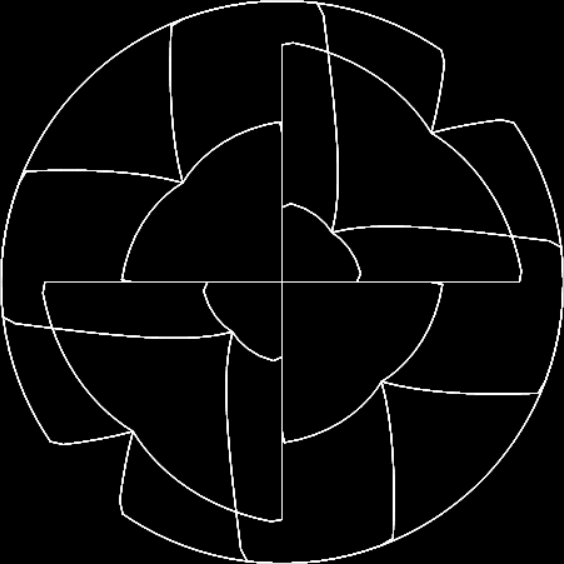

Fractal #2

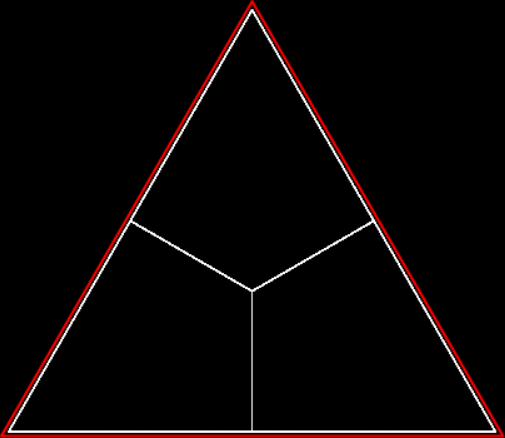

Fractal #3

But even if they are all the same in some mathematical sense, their different appearances matter in an aesthetic sense. Fractal #1 is unattractive and seems uninteresting:

Fractal #1, unattractive, uninteresting and unnamed

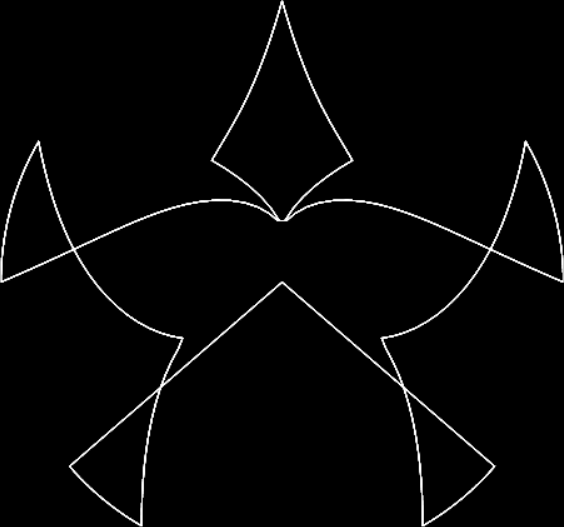

Fractal #3 is attractive and interesting. That’s part of why mathematicians have given it a name, the T-square fractal:

Fractal #3 — the T-square fractal

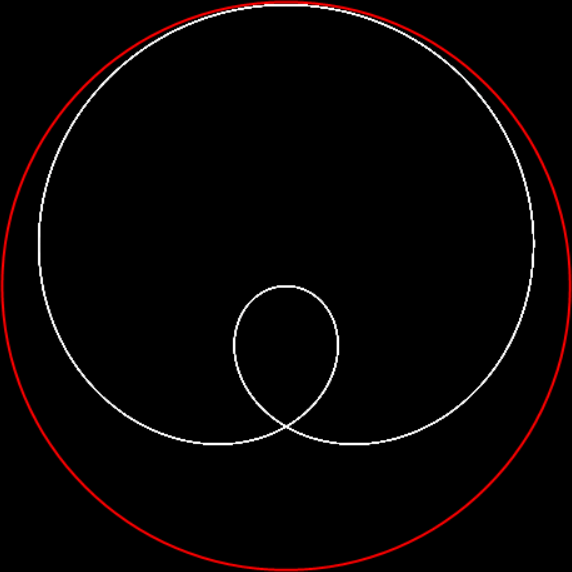

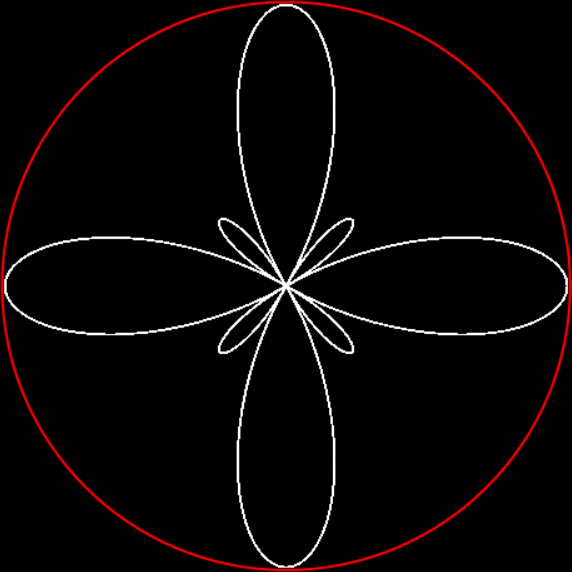

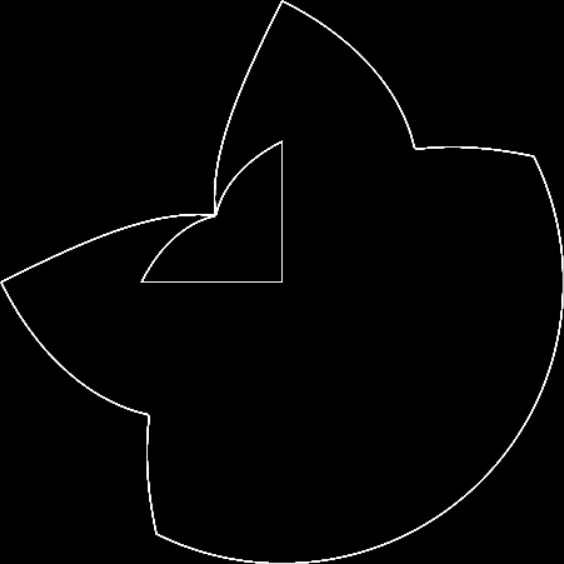

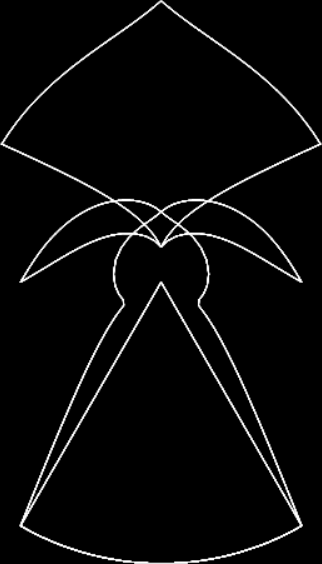

But fractal #2, although it’s attractive and interesting, doesn’t have a name. It reminds me of a ninja throwing-star or shuriken, so I’ve decided to call it the throwing-star fractal or ninja-star fractal:

Fractal #2, the throwing-star fractal

A ninja throwing-star or shuriken

This is one way to construct a throwing-star fractal:

Throwing-star fractal, stage 1

Throwing-star fractal, #2

Throwing-star fractal, #3

Throwing-star fractal, #4

Throwing-star fractal, #5

Throwing-star fractal, #6

Throwing-star fractal, #7

Throwing-star fractal, #8

Throwing-star fractal, #9

Throwing-star fractal, #10

Throwing-star fractal, #11

Throwing-star fractal (animated)

But there’s another way to construct a throwing-star fractal. You use what’s called the chaos game. To understand the commonest form of the chaos game, imagine a ninja inside an equilateral triangle throwing a shuriken again and again halfway towards a randomly chosen vertex of the triangle. If you mark each point where the shuriken lands, you eventually get a fractal called the Sierpiński triangle:

Chaos game with triangle stage 1

Chaos triangle #2

Chaos triangle #3

Chaos triangle #4

Chaos triangle #5

Chaos triangle #6

Chaos triangle #7

Chaos triangle (animated)

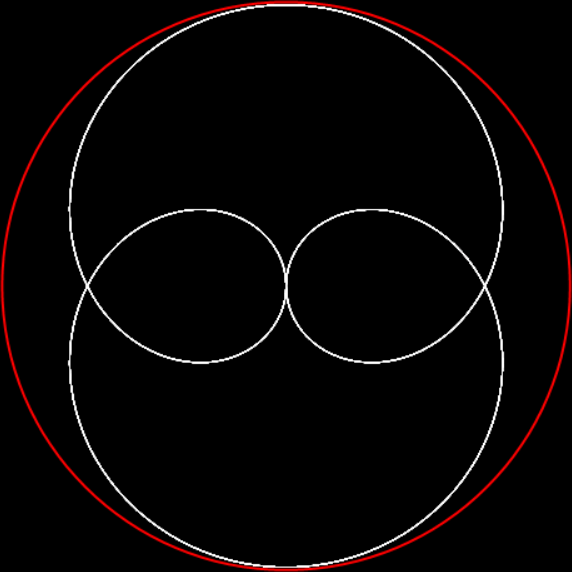

When you try the chaos game with a square, with the ninja throwing the shuriken again and again halfway towards a randomly chosen vertex, you don’t get a fractal. The interior of the square just fills more or less evenly with points:

Chaos game with square, stage 1

Chaos square #2

Chaos square #3

Chaos square #4

Chaos square #5

Chaos square #6

Chaos square (anim)

But suppose you restrict the ninja’s throws in some way. If he can’t throw twice or more in a row towards the same vertex, you get a familiar fractal:

Chaos game with square, ban on throwing towards same vertex, stage 1

Chaos square, ban = v+0, #2

Chaos square, ban = v+0, #3

Chaos square, ban = v+0, #4

Chaos square, ban = v+0, #5

Chaos square, ban = v+0, #6

Chaos square, ban = v+0 (anim)

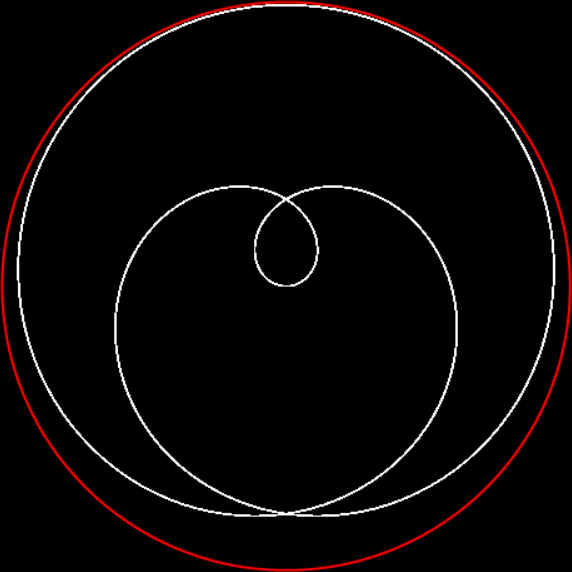

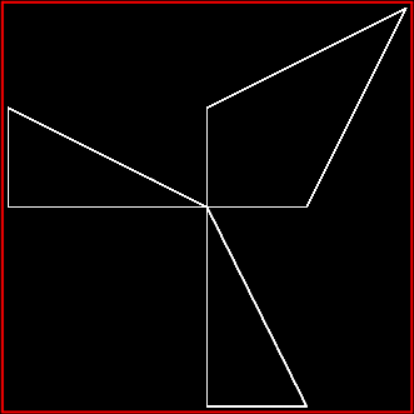

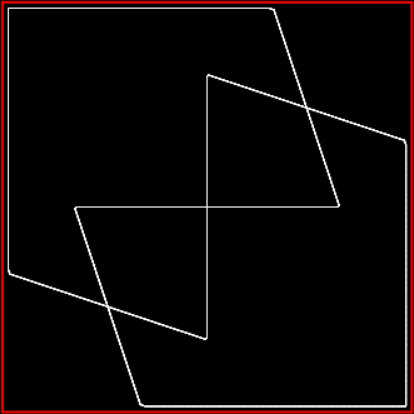

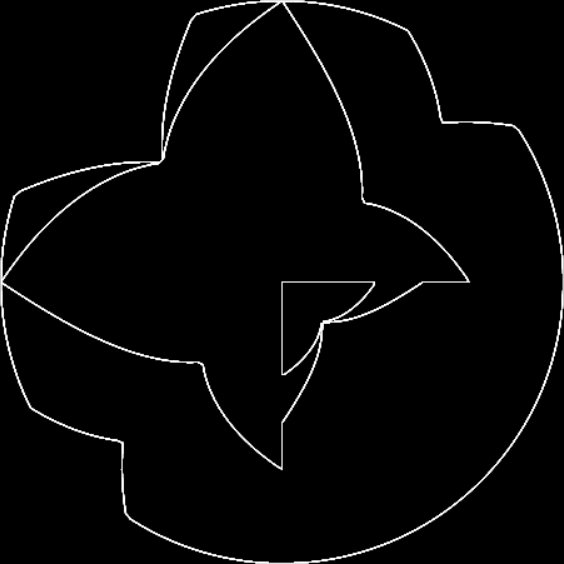

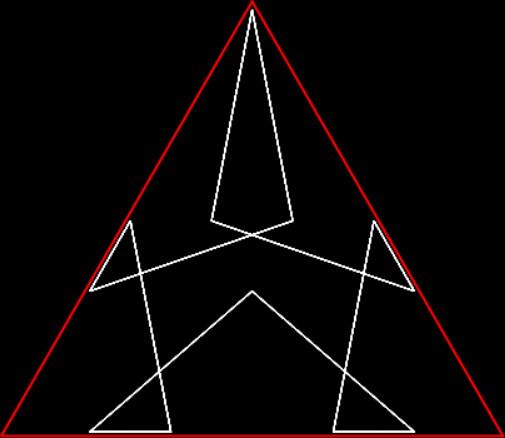

But what if the ninja can’t throw the shuriken towards the vertex one place anti-clockwise of the vertex he’s just thrown it towards? Then you get another familiar fractal — the throwing-star fractal:

Chaos square, ban = v+1, stage 1

Chaos square, ban = v+1, #2

Chaos square, ban = v+1, #3

Chaos square, ban = v+1, #4

Chaos square, ban = v+1, #5

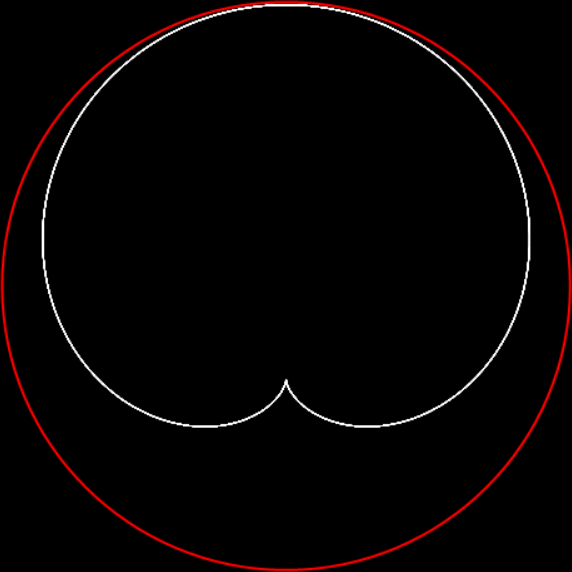

Game of Throwns — throwing-star fractal from chaos game (static)

Game of Throwns — throwing-star fractal from chaos game (anim)

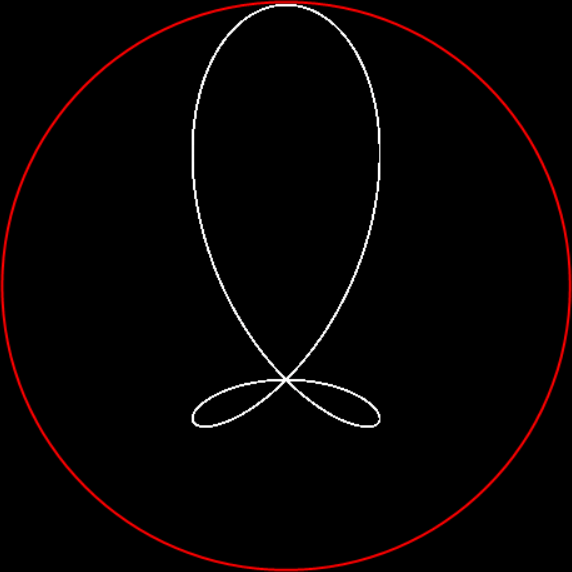

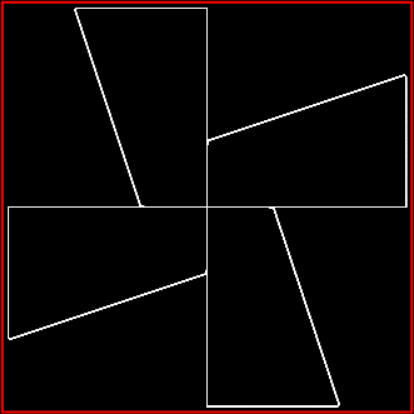

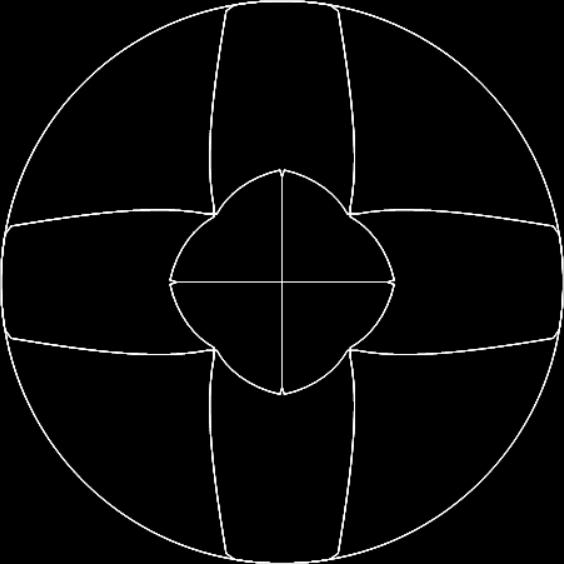

And what if the ninja can’t throw towards the vertex two places anti-clockwise (or two places clockwise) of the vertex he’s just thrown the shuriken towards? Then you get a third familiar fractal — the T-square fractal:

Chaos square, ban = v+2, stage 1

Chaos square, ban = v+2, #2

Chaos square, ban = v+2, #3

Chaos square, ban = v+2, #4

Chaos square, ban = v+2, #5

T-square fractal from chaos game (static)

T-square fractal from chaos game (anim)

Finally, what if the ninja can’t throw towards the vertex three places anti-clockwise, or one place clockwise, of the vertex he’s just thrown the shuriken towards? If you can guess what happens, your mathematical intuition is much better than mine.

Post-Performative Post-Scriptum

I am not now and never have been a fan of George R.R. Martin. He may be a good author but I’ve always suspected otherwise, so I’ve never read any of his books or seen any of the TV adaptations.