Octopus: The Ocean’s Intelligent Invertebrate: A Natural History, Jennifer A. Mather, Roland C. Anderson and James B. Wood (Timber Press, 2010)

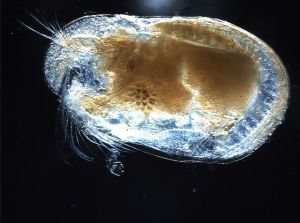

Who knows humanity who only human knows? We understand ourselves better by looking at other animals, but most other animals are not as remarkable as the octopus. These eight-armed invertebrates are much more closely related to oysters, limpets and ship-worms than they are to fish, let alone to mammals, but they lead fully active lives and seem fully conscious creatures of strong and even unsettling intelligence. Octopuses are molluscs, or “soft ones” (the same Latin root is found in “mollify”), with no internal skeleton and no rigid structure. Unlike some of their relatives, however, they do have brains. And more than one brain apiece, in a sense, because their arms are semi-autonomous. They don’t really have bodies, though, which is why they belong to the class known as Cephalopoda, or “head-foots”. Squid and cuttlefish, which are also covered in this book, are in the same class but do have more definite bodies, because they swim in open water rather than, like octopuses, living on the sea-floor. Another difference between the groups is that octopuses don’t have tentacles. Their limbs are too adaptable for that:

Because the arms are lined with suckers along the underside, octopuses can grasp anything. And since the animal has no skeleton, it can flex its arms and move them in any direction. The arms aren’t tentacles: tentacles are used for prey capture in squid, and these arms, with their flexibility, are used for many different actions. (“Introduction: Meet the Octopus”, pg. 15)

Octopuses would be interesting even if we humans knew ourselves perfectly. But one of the interesting things is whether they could be us, given time and opportunity. That is, could they become a tool-making, culture-forming, language-using species like us? After all, unlike most animals, they don’t use their limbs simply for locomotion or aggression: octopuses can manipulate objects with reasonably good precision. I used to think that one obstacle to their use of tools was their inability to make fine discriminations between shapes, because I remembered reading in the Oxford Book of the Mind (2004) that they couldn’t tell cubes from spheres. The explanation there was that their arms are too flexible and can’t, like rigid human arms and fingers, be used as fixed references to judge a manipulated object against. But this book says otherwise:

[The British researcher J.M.] Wells found that common octopuses can learn by touch and can tell a smooth cylinder from a grooved one or a cube from a sphere. They had much more trouble, though, telling a cube with smoothed-off corners from a sphere… They couldn’t learn to distinguish a heavy cylinder from a lighter one with the same surface texture. (ch. 9, “Intelligence”, pg. 130)

The problem isn’t simply that their arms are too flexible: their arms are also too independent:

Maybe the common octopus could not use information about the amount of sucker bending to send to the brain and calculate what an object’s shape would be, or calculate how much the arm bent to figure out weight. Octopuses have a lot of local control of arm movement: there are chains of ganglia [nerve-centres] down the arm and even sucker ganglia to control their individual actions. If local information is processed as reflexes in these ganglia, most touch and position information might not go to the brain and then couldn’t used in associative learning. (Ibid., pg. 130-1)

Or in manipulating an object with high precision and accuracy. An octopus can use rocks to make the entrance to its den narrower and less accessible to predators, but that’s a long way from being able to build a den. It is a start, however, and if man and other apes left the scene, octopuses would be a candidate to occupy his vacant throne one day. But I would give better odds to squirrels and to corvids (crow-like birds) than to cephalopods. Living in the sea may be a big obstacle to developing full, language-using, world-manipulating intelligence. The brevity of that life in the sea is definitely an obstacle: one deep-sea species of octopus may live over ten years, which would be “the longest for any octopus” (ch. 1, “In the Egg”). In shallower, warmer water, the Giant Pacific Octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini, is senescent at three or four years; some other species are senescent at a year or less. Males die after fertilizing the females, females die after guarding their eggs to hatching. In such an active, enquiring animal, senescence is an odd and unsettling process. A male octopus will stop eating, lose weight and start behaving in unnatural ways:

Senescent male giant Pacific octopuses and red octopuses are found crawling out of the water onto the beach [which is] likely to lead to attacks by gulls, crows, foxes, river otters or other animals… Senescent males have even been found in river mouths, going upstream to their eventual death from the low salinity of the fresh water. (ch. 10, “Sex at Last”, pg. 148)

Female octopuses stop eating and lose weight, but can’t behave unnaturally like that, because they have eggs to guard. Evolution keeps them on duty, because females that abandoned their eggs would leave fewer offspring. Meanwhile, males can become what might be called demob-demented: once they’ve mated, their behaviour doesn’t affect their offspring. In the deep sea, longer-lived species follow the same pattern of maturing, mating and senescing, but aren’t so much living longer as living slower. These short, or slow, lives wouldn’t allow octopuses to learn in the way human beings do. The most important part of human learning is, of course, central to this book and this review: language. Cephalopods don’t have good hearing, but they do have excellent sight and the ability to change the colour and patterning of their skin. So Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) suggested in his short-story “The Shining Ones” (1962) that they could become autodermatographers, or “self-skin-writers”, speaking with their skin. The fine control necessary for language is already there:

Within the outer layers of octopus skin are many chromatophores – sacs that contain yellow, red or brown pigment within an elastic container. When a set of muscles pulls a chromatophore sac out to make it bigger, its color is allowed to show. When the muscles relax, the elastic cover shrinks the sac and the color seems to vanish. A nerve connects to each set of chromatophore muscles, so that nervous signals from the brain can cause an overall change in color in less than 100 milliseconds at any point in the body… When chromatophores are contracted, there is another color-producing layer beneath them. A layer of reflecting cells, white leucophores or green iridophores depending on the area of the body, produces color in a different way: Like a hummingbird’s feathers, which only reflect color at a specific angle, these cells have no pigment themselves but reflect all or some of the colors in the environment back to the observer… (ch. 6, “Appearances”, pg. 89)

“Observer” is the operative word: changes in skin-colour, -texture and -shape are a way to fool the eyes and brains of predators. The molluscan octopus can adopt many guises: it can look like rocks, sand or seaweed. But the champion changer is Thaumoctopus mimicus, which lives in shallow waters off Indonesia. Its generic name means “marvel-octopus” and its specific name means “mimicking”. And its modes of mimicry are indeed marvellous:

This octopus can flatten its body and move across the sand, using its jet for propulsion and trailing its arms, with the same undulating motion as a flounder or sole. It can swim above the mud with its striped arms outspread, looking like a venomous lionfish or jellyfish. It can narrow the width of its combined slender body and arms to look like a striped sea-snake. And it may be able to carry out other mimicries we have yet to see. Particularly impressive about the mimic octopus is that not only can it take on the appearance of another animal but it can also assume the behaviour of that animal. (ch. 7, “Not Getting Eaten”, pg. 109)

But octopuses also change their skin to fool the eyes and brains of prey. The “Passing Cloud” may sound like a martial arts technique, but it’s actually a molluscan hunting technique. And it’s produced entirely within the skin, as the authors of this book observed after videotaping octopuses “in an outdoor saltwater pond on Coconut Island”, Hawaii:

Back in the lab and replaying the video frame by frame, we found how complex the Passing Cloud display is. The Passing Cloud formed on the posterior mantle, flowed forward past the head and became more of a bar in shape, then condensed into a small blob below the head. The shape then enlarged and moved out onto the outstretched mantle, flowing off the anterior mantle and disappearing. (ch. 6, “Appearances”, pg. 93)

It’s apparently used to startle crabs that have frozen and are hard to see. When the crab moves in response to the Passing Cloud, the octopus can grab it and bite it to death with its “parrotlike beak”. They “also use venom from the posterior salivary gland that can paralyze prey and start digestion” (ch. 3, “Making a Living”, pg. 62). But a bite from an octopus can kill much bigger things than crabs:

Blue-ringed octopuses, the four species that are members of the genus Hapalochlaena, display stunning coloration. Like other spectacular forms of marine and terrestrial life, they have vivid color patterns as a warning signal. These small octopuses pose a serious threat to humans. They pack a potent venomous bite that makes them among the most dangerous creatures on Earth. Their venom, the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin (TTX) described by Scheumack et al in 1978, is among the few cephalopod venoms that can affect humans. A variety of marine and terrestrial animals produce TTX [including] poisonous arrow frogs [untrue, according to Wikipedia, which refers to “toads of the genus Atelopus” instead], newts, and salamanders… but the classic example, and what the compound is named after, is the tetraodon puffer fish. The puffers are what the Japanese delicacy fufu is made from. If the fish is prepared correctly, extremely small amounts of TTX cause only a tingling or numbing sensation. But if it is prepared incorrectly, the substance kills by blocking sodium channels on the surface of nerve membranes. A single milligram, 1/2500 of the weight of a penny, will kill an adult human… Even in the minuscule doses delivered by a blue-ringed octopus’s nearly unnoticeable bite, TTX can shut down the nervous system of a large person in just minutes; the risk of death is very high. (“Postscript: Keeping a Captive Octopus”, pg. 170)

It’s interesting to see how often toxicity has evolved among animals. Puffer-fish and blue-ringed octopuses may get their toxin from bacteria or algae, while poison-arrow frogs get the even more potent batrachotoxin from eating beetles, as do certain species of bird on New Guinea. Accordingly, toxicity is found in animals with no legs, two legs, four legs, six legs, eight legs and ten legs (if squid have a poisonous bite too). Evolution has found similar solutions to similar problems in unrelated groups, because evolution is a way of exploring space: that of possibility. And it is all, in one way or another, chemical possibility. Blue-ringed octopuses have found a chemical solution to hunting and evading predators. Other cephalopods have found a chemical solution to staying afloat:

Another substance used to keep plankton buoyant is ammonia, again lighter than water. Ammonia is primarily used by the large squid species, including the giant squid (Architeuthis dux), in their tissues, although the glass squid (Cranchia scabra) concentrates ammonia inside a special organ. The ammonia in the tissues of these squid makes the living or dead animal smell pungent. Dead or dying squid on the ocean’s surface smell particularly foul. The ammonia in these giant squid also makes them inedible – there will be no giant squid calamari. (ch. 2, “Drifting and Settling”)

Other deep-sea solutions from chemical possibility-space include bioluminescence. This is used by a cephalopod that was little-known until it was used as a metaphor for the greedy behaviour of Goldman-Sachs and other bankers:

…although they do not have an ink-sac, vampire squid have a bioluminescent mucus that they can jet out, presumably at the approach of a potential predator, likely distracting it in the same way as a black ink jet for a shallow-water octopus or squid. Second, they have a pair of light organs at the base of the fins with a moveable flap that can be used as a shutter. These could act as a searchlight, turning a beam of light onto a potential prey species that tactile sensing from the [tentacle-like] filaments has picked up. And third, they have a huge number of tiny photophores all over the body and arms. These could work two ways: they might give a general dim lighting as a visual counter-shading. With even a little light from above, a dark animal would stand out in silhouette from below. With low-level light giving just enough illumination, it could blend in. And the second function of these lights has been seen by ROV [remotely operated underwater vehicle] viewers: a disturbed vampire squid threw its arms back over its body and flashed the lights on the arms, which should startle any creature. (ch. 11, “The Rest of the Group”, pg. 161)

I was surprised to learn that vampire squid can be prey, but in fact their scientific name – Vampyroteuthis infernalis – is almost as big as they are: “for those imagining that vampire squid are monsters of the deep, they are tiny – only up to 5 in. (13 cm) long” (ibid., pg. 162). Even less-studied, even deeper-living, and even longer-named is Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis, the “specialized deep-sea vent octopus”, which is “found, as its name suggests, near deep-sea hydrothermal vents way down at 6000 ft. (2000 m)” (“Introduction: Meet the Octopus”, pg. 15). Life around hydrothermal vents, or mini-volcanoes on the ocean floor, is actually independent of the sun, because the food-pyramid there is based on bacteria that live on the enriched water flowing from the vents. So an asteroid strike or mega-volcano that clouded the skies and stopped photosynthesis wouldn’t directly affect that underwater economy. But vents sometimes go extinct and Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis must lead a precarious existence.

I’d like to know more about the species, but it’s one interesting octopus among many. This book is an excellent introduction to this eight-limbed group and cousins like the ten-limbed squid and the sometimes ninety-limbed nautiluses. It will guide you through all aspects of their lives and behaviour, from chromatophores, detachable arms and jet propulsion to siphuncles, glue-glands and the hectocotylus, the “modified mating arm” of male cephalopods that was once thought to be a parasitic worm. That mystery has been solved, but lots more remain. Octopus: The Ocean’s Intelligent Invertebrate should appeal to any thalassophile who shares the enthusiasm of H.P. Lovecraft or Arthur C. Clarke for a group that has evolved high intelligence without ever leaving the ocean.