I had only one problem with Cormac McCarthy. He was crap.

More later.

Okay?

For now, let’s consider another famous writer. Millions of people have been writing English for hundreds of years. So the competition is intense for “Worst Simile Ever Written in English”. I still think this must be a leading contender:

Billy Nolan was at the pink fuzz-covered wheel [of the car]. Jackie Talbot, Henry Blake, Steve Deighan, and the Garson brothers, Kenny and Lou, were also squeezed in. Three joints were going, passing through the inner dark like the lambent eyes of some rotating Cerberus.

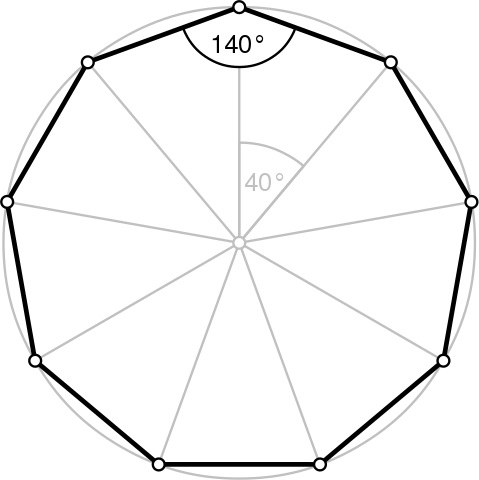

That’s from Stephen King’s Carrie (1974), describing some ill-intentioned teenagers smoking joints in a car. The paragraph starts gently and unpretentiously, lulling you into a false sense of security. Then wham! It hits you with “like the lambent eyes of some rotating Cerberus”. And where do I begin to dissect the wrongness of that simile? It’s simultaneously pretentious and illogical and ill-judged and anachronistic and clankingly clumsy and just plain stoopid. So where do I begin? Okay, I’ll begin with this observation: Cerberus had six eyes, not three (he had three heads, remember). So how did his six “lambent eyes” look like three glowing joints? Were his eyes very close-set? Did he keep three of them closed? Was he in fact part-dog, part-Cyclops, so that he only had three eyes after all? Yes, by “rotating” King means that now the three right eyes, now the three left eyes of Cerberus are visible, but there would be times when all six eyes were visible. And why is Cerberus rotating anyway?

I don’t know. And those questions by no means exhaust the idiotic possibilities raised by the simile. Let’s now ask how King’s lambent-eyed Cerberus was “rotating”. If his whole body was rotating on a vertical axis through his shoulders, say, then his three heads and six eyes would have been following too big an arc to fit the scene. So one has to assume that it was only his three heads and six eyes rotating on his one neck. Round and round and round. Which is a ridiculous image, not an eerie or ominous one.

No, we gotta face facts: King aimed for the Underworld and shot himself in the arse. And for the icing on the cake, we’ve got that poetic “some”. It wasn’t “a rotating Cerberus”, which would have been quite bad enough. It was “some rotating Cerberus”, as though King was setting his simile gently and carefully down on a bed of black velvet or plinth of polished obsidian, awestruck by the depth of his own erudition and the breadth of his own imagination. Fair enough: he’s human, he erred, I can forgive him. But how did the simile get past his editor and publisher and wife? Why did someone not say to him: “Steve, I like the book, in fact I love the book, but that appalling simile in part one has just gotta go?” Or why didn’t an editor suggest a re-write? I’d suggest this:

• Three joints were going, shifting in the inner dark like the glowing eyes of a watchful Cerberus.

Now the simile kinda works. The teenagers are up to something evil, but they don’t know that they’re going to unleash hell and harm themselves too. There’s authorial irony in the simile now: the hell-hound Cerberus is with them in spirit, conjured by the passing of the joints, but they, as characters in the story, don’t know it. They don’t know that Cerberus is patiently watching them, waiting to feast on their souls. I think the re-write removes the pretentiousness of linking ’70s American teenagers in a car with a monster from Greek mythology. The teenagers are evil but petty. It’s appropriate that they’re ignorant of grander and grotesquer things, like the three-headed hell-hound Cerberus and the telekinetic powers of the girl they’re planning to humiliate.

Alas, King or one of his editors didn’t re-write the simile. The original stayed put and turned the sentence into one of the worst I’ve ever read. And it was definitely the worst I’ve ever read in a book by Stephen King. That simile was bad by King’s own standards, because he’s not usually a pretentious or preening writer. So why did he write so badly there? I suspect the malign influence of another and much more critically acclaimed writer: the recently deceased Cormac McCarthy, who is easily the most pretentious and over-rated writer I’ve ever come across. I couldn’t finish Blood Meridian (1985) and although I did manage to finish The Road (2006), it didn’t change my opinion of the author. Cormac is crap. But Stephen King takes him seriously and, I suspect, was paying some kind of misguided homage to him when he came up with that appallingly bad “like the lambent eyes of some rotating Cerberus.”

If I’d read more of Cormac McCarthy’s books, I might be able to provide stronger evidence of my theory about his malign influence on that particular sentence in Carrie. But why would I want to read more of Cormac McCarthy’s books? I’m not a masochist and I don’t like reading bad English and pretentious prose. All the same, here’s a bit from The Road that suggests to me that King was imitating Cormac:

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world. His hand rose and fell softly with each precious breath. He pushed away the plastic tarpaulin and raised himself in the stinking robes and blankets and looked toward the east for any light but there was none. In the dream from which he’d wakened he had wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand. Their light playing over the wet flowstone walls. Like pilgrims in a fable swallowed up and lost among the inward parts of some granitic beast.

There’s a lot of bad writing there, but I want to look at the two similes. They both use bad and pretentious imagery and they both have a would-be poetic “some”. Take the first simile. What on earth is a “cold glaucoma”? That doesn’t make sense. It isn’t the glaucoma that’s cold: it’s the way the glaucoma makes the world appear. “Cold glaucoma” is certainly an interesting medical concept, but it’s crap writing in a novel. Now take the second simile. What on earth is a “granitic beast”? If a beast is made of granite, how does it swallow people, let alone digest them? Granite is very solid and very rigid. The simile doesn’t work. And why did McCarthy say “inward parts” rather than the stronger “bowels”? Because he was doing what he did so often: writing badly and carelessly and pretentiously. “Granitic beast” is a stoopid image and the pretentious “granitic” makes it even worse.

Okay, neither simile is as bad as King’s “lambent-eyes-of-Cerberus” atrocity, but I detect a family resemblance and I think that King was trying to imitate some earlier writing by McCarthy. He shouldn’t have done. The ironic thing is that King himself is a better writer than McCarthy. I am too. But then who isn’t? It’s much easier to think of writers who are better than Cormac McCarthy than of writers who are worse. Let’s see: Will Self is worse. But who else? I’m glad to say that I can’t come up with anyone else. If I could come up with someone else, I would’ve suffered by reading another very bad writer.

Anyway, here’s my re-write of that extract from The Road:

When he woke in the woods in the dark and cold he’d reach out and touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and each day grayer than the day before, as though he viewed the world through dying eyes. His hand rose and fell softly with each breath. He pushed away the tarpaulin and raised himself in the stinking blankets and looked toward the east for light. In the dream from which he’d wakened he had wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand. Light played over the wet flowstone walls. They seemed like travelers in a story, swallowed and lost in the bowels of a petrified giant.

That’s still not very good, but it’s a definite improvement. If you don’t agree, you have a cloth ear for prose. And here’s my review of the whole book from 2013:

Highway to Hell

Cormac McCarthy won the Pulitzer Prize for The Road in 2007. The book is set in the aftermath of a world-wide cataclysm.

So is Stephen King’s The Stand (1978).

But The Road is much shorter than The Stand.

It makes up for this by being

much more pre

tentious

too.

Okay?

It is also much

less enter

taining.

Which is not to say that

The Road doesn’t have its

entertain

ing

bits.

For example

(spoiler alert)

the bit where the

unnamedfatherandsonprotagonists

go

into a wood and find

a fire where

some folks (far from

unferal)

have been preparing to

roast

and

eat a

b

a

b

y

.

.

.

For me

this was a

laugh-

out-loud mo

ment.

The “catamites” were pretty

funny

,

also

.

If you take Cormac McCarthy

seriously

my brother (or

sister)

I think that

you need to

grow up.

Okay?

But you

probably

nev

er

w

i

l

l

.

.

.

Elsewhere Other-Accessible…

• A Reader’s Manifesto — B.R. Myers agrees with me about McCarthy, inter alios (et alias)