European Reptile and Amphibian Guide, Axel Kwet (New Holland 2009)

European Reptile and Amphibian Guide, Axel Kwet (New Holland 2009)

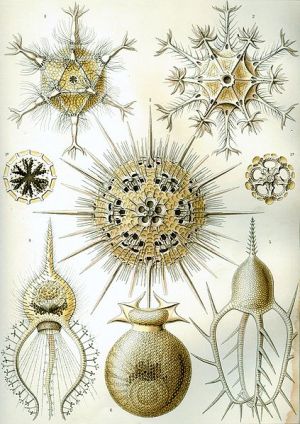

An attractive book about animals that are mostly attractive, sometimes strange, always interesting. It devotes photographs and descriptive text to all the reptiles and amphibians found in Europe, from tree-frogs to terrapins, from skinks to slow-worms. Some of the salamanders look like heraldic mascots, some of the lizards like enamel jewellery, and some of the toads like sumo wrestlers with exotic skin-diseases. When you leaf through the book, you’ve moving through several kinds of space: geographic and evolutionary, aesthetic and psychological. Europe is a big place and has a lot of reptilian and amphibian variety, including one species of turtle, the loggerhead, Caretta caretta, and one species of chameleon, the Mediterranean, Chamaeleo chamaeleon.

But every species, no matter how dissimilar in size and appearance, has a common ancestor: the tiny crested newt (Triturus cristatus) to the far north-west in Scotland and the two-and-a-half metre whip snake (Dolichophis caspius) to the far south-east in Greece; the sun-loving Hermann’s tortoise (Testudo hermanni), with its sturdy shell, and the pallid and worm-like olm (Proteus anguinus), which lives in “underground streams in limestone karst country along the coast from north-east Italy to Montenegro” (pg. 55). Long-limbed or limbless, sun-loving or sun-shunning, soft-skinned or scaly – they’re all variations on a common theme.

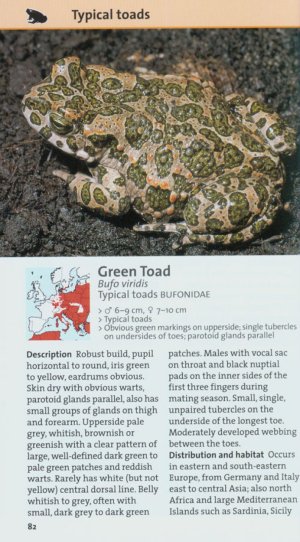

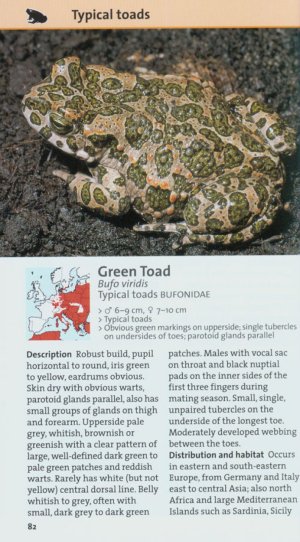

Sample page from European Reptile and Amphibian Guide

And that’s where aesthetic and psychological space comes in, because different species and families evoke different impressions and emotions. Why do snakes look sinister and skinks look charming? But snakes are sinuous too and in a way it’s a shame that a photograph can capture their endlessly varying loops and curves as easily as it can capture the ridigity of a tortoise. At one time a book like this would have had paintings or drawings. Nowadays, it has photographs. The images are more realistic but less enchanted: the images are no longer mediated by the hand, eye and brain of an artist. But some enchantment remains: the glass lizard,

Pseudopus apodus, peering from a holly bush on page 199 reminds me of Robert E. Howard’s

“The God in the Bowl”, because there’s an alien intelligence in its gaze. Glass lizards are like snakes but can blink and retain “tiny, barely visible vestiges of the hind legs” (pg. 198).

Other snake-like reptiles retain vestiges of the fore-limbs too, like the Italian three-toed skink (Chalcides chalcides). The slow-worm, Anguis fragilis, has lost its limbs entirely, but doesn’t look sinister like a snake and can still blink. Elsewhere, some salamanders have lost not limbs but lungs: the Italian cave salamander, Speleomantes italicus, breathes through its skin and the lining of its mouth. So does Gené’s cave salamander, Speleomantes genei, which is found only on the island of Sardinia. It “emits an aromatic scent when touched” (pg. 54). Toads can emit toxins and snakes can inject venoms: movement in evolutionary space means movement in chemical space, because every alteration in an animal’s appearance and anatomy involves an alteration in the chemicals created by its body. But chemical space is two-fold: genotypic and phenotypic. The genes change and so the products of the genes change. The external appearance of every species is like a bookmark sticking out of the Book of Life, fixing its position in gene-space. You have to open that book to see the full recipe for the animal’s anatomy, physiology and behaviour, though not everything is specified by the genes.

The force of gravity is one ingredient in an animal’s development, for example. So is sunlight or its absence. Or water, sand, warmth, cold. The descendants of that common ancestor occupy many ecological niches. And in fact one of those descendants wrote this book: humans and all other mammals share an ancestor with frogs, skinks and vipers. Before that, we were fish. So a plaice is a distant cousin of an olm, despite the huge difference in their appearance and habitat. One is flat, one is tubular. One lives in the sea, one lives in caves. But step by step, moving through genomic and topological space, you can turn a plaice into an olm. Or into anything else in this book. Just step back through time to the common ancestor, then take another evolutionary turning. One ancestor, many descendants. That ancestor was itself one descendant among many of something even earlier.

Olm in a Slovenian cave

But there’s another important point: once variety appeared, it began to interact with itself. Evolutionary environment includes much more than the inanimate and inorganic. We mammals share more than an ancestor with reptiles and amphibians: we’ve also shared the earth. So we’re written into their genes and some of them are probably written into ours. Mammalian predators have influenced the evolution of skin-colour and psychology, making some animals camouflaged and cautious, others obtrusive and aggressive. But it works both ways: perhaps snakes seem sinister because we’re born with snake-sensitive instincts. If it’s got no limbs and it doesn’t blink, it might have a dangerous bite. That’s why the snake section of this book seems so different to the salamander section or the frog section. But all are interesting and all are important. This is a small book with some big themes.