Fingers are fractal. Where a tree has a trunk, branches and twigs, a human being has a torso, arms and fingers. And human beings move in fractal ways. We use our legs to move large distances, then reach out with our arms over smaller distances, then move our fingers over smaller distances still. We’re fractal beings, inside and out, brains and blood-vessels, fingers and toes.

But fingers are fractal are in another way. A digit – digitus in Latin – is literally a finger, because we once counted on our fingers. And digits behave like fractals. If you look at numbers, you’ll see that they contain patterns that echo each other and, in a sense, recur on smaller and smaller scales. The simplest pattern in base 10 is (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). It occurs again and again at almost very point of a number, like a ten-hour clock that starts at zero-hour:

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9…

10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19…

200… 210… 220… 230… 240… 250… 260… 270… 280… 290…

These fractal patterns become visible if you turn numbers into images. Suppose you set up a square with four fixed points on its corners and a fixed point at its centre. Let the five points correspond to the digits (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) of numbers in base 6 (not using 0, to simplify matters):

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65… 2431, 2432, 2433, 2434, 2435, 2441, 2442, 2443, 2444, 2445, 2451, 2452…

Move between the five points of the square by stepping through the individual digits of the numbers in the sequence. For example, if the number is 2451, the first set of successive digits is (2, 4), so you move to a point half-way between point 2 and point 4. Next come the successive digits (4, 5), so you move to a point half-way between point 4 and point 5. Then come (5, 1), so you move to a point half-way between point 5 and point 1.

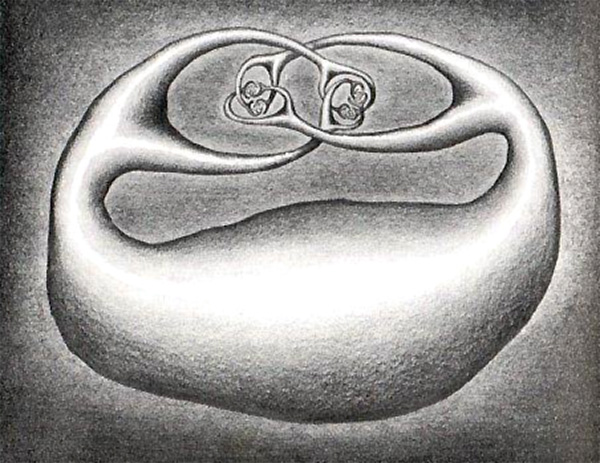

When you’ve exhausted the digits (or frigits) of a number, mark the final point you moved to (changing the colour of the pixel if the point has been occupied before). If you follow this procedure using a five-point square, you will create a fractal something like this:

A pentagon without a central point using numbers in a zero-less base 7 looks like this:

A pentagon with a central point looks like this:

Hexagons using a zero-less base 8 look like this:

But the images above are just the beginning. If you use a fixed base while varying the polygon and so on, you can create images like these (here is the program I used):