If you’re a fan of Black Sabbath, you may have misread the title of this blog-post. But it’s not “Spiral Architect”, it’s “Sphiral Architect”. And this is a sphiral:

A sphiral

(the red square is the center)

But why do I call it a sphiral? The answer starts with the Fibonacci sequence, which is at once a perfectly simple and profoundly complex sequence of numbers. It’s very easy to create, yet yields endless riches. Simply seed the sequence with 1s, then add the previous two numbers in the sequence to get the next:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946, 17711, 28657, 46368, 75025, 121393, 196418, 317811, 514229, 832040, 1346269, 2178309, 3524578, 5702887, 9227465, 14930352, 24157817, 39088169, 63245986, 102334155, 165580141, 267914296, 433494437, 701408733, 1134903170, 1836311903, 2971215073, 4807526976, 7778742049, 12586269025...

Each pair of numbers provides a better and better approximation to phi or φ, an irrational number whose decimal digits never end and never fall into a repeating pattern. It satisfies the equations 1/x = x-1 and x^2 = x+1:

1.6180339887498948482045868343656381177203091798... = φ

1 / 1.6180339887498948482045868343656381177203091798... = 0.6180339887498948482045868343656381177203091798...

1.6180339887498948482045868343656381177203091798...^2 = 2.6180339887498948482045868343656381177203091798...

Here are the approximations to φ supplied by successive pairs of numbers in the Fibonacci sequence:

1 = 1/1

2 = 2/1

1.5 = 3/2

1.666... = 5/3

1.6 = 8/5

1.625 = 13/8

1.6153846153846... = 21/13

1.619047619047619047619047... = 34/21

1.6176470588235294117647... = 55/34

1.6181818... = 89/55

1.617977528... = 144/89

1.6180555... = 233/144

1.618025751... = 377/233

1.6180371352785... = 610/377

1.6180327868852459... = 987/610

1.618034447821681864235... = 1597/987

1.6180338134... = 2584/1597

1.61803405572755... = 4181/2584

1.6180339631667... = 6765/4181

1.6180339985218... = 10946/6765

1.618033985... = 17711/10946

1.61803399... = 28657/17711

1.6180339882... = 46368/28657

1.6180339889579... = 75025/46368

1.61803398867... = 121393/75025

1.61803398878... = 196418/121393

1.6180339887383... = 317811/196418

1.6180339887543225376... = 514229/317811

1.6180339887482... = 832040/514229

1.61803398875... = 1346269/832040

1.6180339887496481... = 2178309/1346269

1.618033988749989... = 3524578/2178309

1.61803398874985884835... = 5702887/3524578

1.6180339887499... = 9227465/5702887

1.6180339887498895958965978... = 14930352/9227465

1.6180339887498968544... = 24157817/14930352

1.618033988749894... = 39088169/24157817

1.61803398874989514... = 63245986/39088169

1.6180339887498947364... = 102334155/63245986

1.61803398874989489... = 165580141/102334155

1.618033988749894831892914... = 267914296/165580141

1.618033988749894854435... = 433494437/267914296

1.618033988749894845824745843278261031063704284629608753202985163 = 701408733/433494437

1.6180339887498948491136... = 1134903170/701408733

1.618033988749894847857... = 1836311903/1134903170

1.61803398874989484833721... = 2971215073/1836311903

1.6180339887498948481... = 4807526976/2971215073

1.61803398874989484822... = 7778742049/4807526976

1.618033988749894848197... = 12586269025/7778742049

1.6180339887498948482... = 20365011074/12586269025

1.6180339887498948482045868343656381177203091798... = φ

I decided to look at how integers could be the partial sums of unique Fibonacci numbers. For example:

Using 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89...

1 = 1

2 = 2

3 = 1+2 = 3

4 = 1+3

5 = 2+3 = 5

6 = 1+2+3 = 1+5

7 = 2+5

8 = 1+2+5 = 3+5 = 8

9 = 1+3+5 = 1+8

10 = 2+3+5 = 2+8

11 = 1+2+3+5 = 1+2+8 = 3+8

12 = 1+3+8

13 = 2+3+8 = 5+8 = 13

14 = 1+2+3+8 = 1+5+8 = 1+13

15 = 2+5+8 = 2+13

16 = 1+2+5+8 = 3+5+8 = 1+2+13 = 3+13

17 = 1+3+5+8 = 1+3+13

18 = 2+3+5+8 = 2+3+13 = 5+13

19 = 1+2+3+5+8 = 1+2+3+13 = 1+5+13

20 = 2+5+13

21 = 1+2+5+13 = 3+5+13 = 8+13 = 21

22 = 1+3+5+13 = 1+8+13 = 1+21

23 = 2+3+5+13 = 2+8+13 = 2+21

24 = 1+2+3+5+13 = 1+2+8+13 = 3+8+13 = 1+2+21 = 3+21

25 = 1+3+8+13 = 1+3+21

26 = 2+3+8+13 = 5+8+13 = 2+3+21 = 5+21

27 = 1+2+3+8+13 = 1+5+8+13 = 1+2+3+21 = 1+5+21

28 = 2+5+8+13 = 2+5+21

29 = 1+2+5+8+13 = 3+5+8+13 = 1+2+5+21 = 3+5+21 = 8+21

30 = 1+3+5+8+13 = 1+3+5+21 = 1+8+21

31 = 2+3+5+8+13 = 2+3+5+21 = 2+8+21

All integers can be represented as partial sums of unique Fibonacci numbers. But what happens when you start removing numbers from the beginning of the Fibonacci sequence, then trying to find partial sums of the integers? Some integers are sumless:

Using 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144...

1 has no sum

2 = 2

3 = 3

4 has no sum

5 = 2+3 = 5

6 has no sum

7 = 2+5

8 = 3+5 = 8

9 has no sum

10 = 2+3+5 = 2+8

11 = 3+8

12 has no sum

13 = 2+3+8 = 5+8 = 13

14 has no sum

15 = 2+5+8 = 2+13

16 = 3+5+8 = 3+13

17 has no sum

18 = 2+3+5+8 = 2+3+13 = 5+13

19 has no sum

20 = 2+5+13

21 = 3+5+13 = 8+13 = 21

22 has no sum

23 = 2+3+5+13 = 2+8+13 = 2+21

24 = 3+8+13 = 3+21

25 has no sum

26 = 2+3+8+13 = 5+8+13 = 2+3+21 = 5+21

27 has no sum

28 = 2+5+8+13 = 2+5+21

29 = 3+5+8+13 = 3+5+21 = 8+21

30 has no sum

31 = 2+3+5+8+13 = 2+3+5+21 = 2+8+21

Now try removing more Fibonacci numbers from the sequence:

Using 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233...

1 to 2 have no sums

3 = 3

4 has no sum

5 = 5

6 to 7 have no sums

8 = 3+5 = 8

9 to 10 have no sums

11 = 3+8

12 has no sum

13 = 5+8 = 13

14 to 15 have no sums

16 = 3+5+8 = 3+13

17 has no sum

18 = 5+13

19 to 20 have no sums

21 = 3+5+13 = 8+13 = 21

22 to 23 have no sums

24 = 3+8+13 = 3+21

25 has no sum

26 = 5+8+13 = 5+21

27 to 28 have no sums

29 = 3+5+8+13 = 3+5+21 = 8+21

30 to 31 have no sums

32 = 3+8+21

Using 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377...

1 to 4 have no sums

5 = 5

6 to 7 have no sums

8 = 8

9 to 12 have no sums

13 = 5+8 = 13

14 to 17 have no sums

18 = 5+13

19 to 20 have no sums

21 = 8+13 = 21

22 to 25 have no sums

26 = 5+8+13 = 5+21

27 to 28 have no sums

29 = 8+21

30 to 33 have no sums

34 = 5+8+21 = 13+21 = 34

35 to 38 have no sums

39 = 5+13+21 = 5+34

40 to 41 have no sums

42 = 8+13+21 = 8+34

43 to 46 have no sums

47 = 5+8+13+21 = 5+8+34 = 13+34

48 to 51 have no sums

52 = 5+13+34

Using 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610...

1 to 7 have no sums

8 = 8

9 to 12 have no sums

13 = 13

14 to 20 have no sums

21 = 8+13 = 21

22 to 28 have no sums

29 = 8+21

30 to 33 have no sums

34 = 13+21 = 34

35 to 41 have no sums

42 = 8+13+21 = 8+34

43 to 46 have no sums

47 = 13+34

48 to 54 have no sums

55 = 8+13+34 = 21+34 = 55

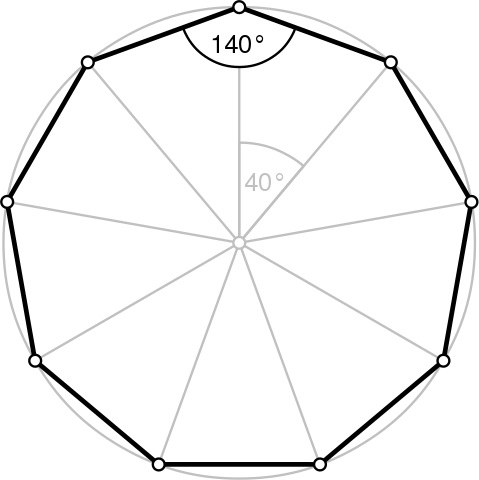

Now ask: what fraction of integers can’t be represented as sums as you remove 1,2,3,5… from the Fibonacci sequence? Let’s approach the answer visually and represent the sums on a spiral created in the same way as an Ulam spiral. When the Fib-sums can’t use 1, you get this spiral:

2,3,5-sphiral

(integers that are the partial sums of unique Fibonacci numbers from 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89…)

I call it a sphiral, because φ appears in the ratio of white-to-black space in the spiral, as we shall see. Phi also appears in these sphirals:

3,5,8,13-sphiral

5,8,13,21-sphiral

8,13,21,34-sphiral

Sum sphirals from 1,2,3,5 to 8,13,21,34(animated)

How does φ appear in the sphirals? Well, I think it must appear in lots more ways than I’m able to see. But one simple way, as remarked above, is that φ governs the ratio of white-to-black space in each sphiral. When all Fibonacci numbers can be used, there’s no black space, because all integers can be represented as sums of 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89… But that changes as numbers are dropped from the beginning of the Fibonacci sequence:

0.6180339887... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144...

0.6180339887... = 1/φ^1

0.3819660112... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233...

0.3819660112... = 1/φ^2

0.2360679774... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377...

0.2360679774... = 1/φ^3

0.1458980337... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610...

0.1458980337... = 1/φ^4

0.0901699437... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987...

0.0901699437... = 1/φ^5

0.05572809... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597...

0.05572809... = 1/φ^6

0.0344418537... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584...

0.0344418537... = 1/φ^7

0.0212862362... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181...

0.0212862362... = 1/φ^8

0.0131556174... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765...

0.0131556174... = 1/φ^9

0.0081306187... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, 10946...

0.0081306187... = 1/φ^10

But why stick to the standard Fibonacci sequence? If you seed a Fibonacci-like sequence with 2s instead of 1s, you get these numbers:

2, 2, 4, 6, 10, 16, 26, 42, 68, 110, 178, 288, 466, 754, 1220, 1974, 3194, 5168, 8362, 13530, 21892, 35422, 57314, 92736, 150050, 242786, 392836, 635622, 1028458, 1664080, 2692538, 4356618, 7049156, 11405774, 18454930, 29860704, 48315634, 78176338, 126491972, 204668310...

Obviously, all numbers in the 2,2,4-sequence are even, so no odd number is the partial sum of unique numbers in the sequence. But all even numbers are partial sums of the sequence. In other words:

0.5 of integers can be represented as partial sums of 2, 2, 4, 6, 10, 16, 26, 42, 68, 110...

So what happens when you drop the 2s and represent the sums graphically? You get this attractive sphiral:

4,6,10,16-sphiral (lo-res)

4,6,10,16-sphiral (hi-res)

In the 4,6,10,16-sphiral, the ratio of white-to-black space is 0.3090169943749474241… This is because:

0.3090169943749474241... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 4, 6, 10, 16, 26, 42, 68, 110, 178, 288...

0.3090169943749474241... = φ^1 * 0.5

Now try the 6,10,16,26-sphiral and 10,16,26,42-sphiral:

6,10,16,26-sphiral

10,16,26,42-sphiral

In the 4,6,10,16-sphiral, the ratio of white-to-black space is 0.190983005625… This is because:

0.190983005625... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 6, 10, 16, 26, 42, 68, 110, 178, 288, 466...

0.190983005625... = φ^2 * 0.5

And so on:

0.1180339887498948482... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 10, 16, 26, 42, 68, 110, 178, 288, 466, 754...

0.1180339887498948482... = φ^3 * 0.5

0.072949016875... of integers can be represented as partial sums of 16, 26, 42, 68, 110, 178, 288, 466, 754, 1220...

0.072949016875... = φ^4 * 0.5