Echinops sphaerocephalus, or Great Globe Thistle

Echinops sphaerocephalus, or Great Globe Thistle

A polyiamond is a shape consisting of equilateral triangles joined edge-to-edge. There is one moniamond, consisting of one equilateral triangle, and one diamond, consisting of two. After that, there are one triamond, three tetriamonds, four pentiamonds and twelve hexiamonds. The most famous hexiamond is known as the sphinx, because it’s reminiscent of the Great Sphinx of Giza:

It’s famous because it is the only known pentagonal rep-tile, or shape that can be divided completely into smaller copies of itself. You can divide a sphinx into either four copies of itself or nine copies, like this (please open images in a new window if they fail to animate):

So far, no other pentagonal rep-tile has been discovered. Unless you count this double-triangle as a pentagon:

It has five sides, five vertices and is divisible into sixteen copies of itself. But one of the vertices sits on one of the sides, so it’s not a normal pentagon. Some might argue that this vertex divides the side into two, making the shape a hexagon. I would appeal to these ancient definitions: a point is “that which has no part” and a line is “a length without breadth” (see Neuclid on the Block). The vertex is a partless point on the breadthless line of the side, which isn’t altered by it.

But, unlike the sphinx, the double-triangle has two internal areas, not one. It can be completely drawn with five continuous lines uniting five unique points, but it definitely isn’t a normal pentagon. Even less normal are two more rep-tiles that can be drawn with five continuous lines uniting five unique points: the fish that can be created from three equilateral triangles and the fish that can be created from four isosceles right triangles:

When I started to look at rep-tiles, or shapes that can be divided completely into smaller copies of themselves, I wanted to find some of my own. It turns out that it’s easy to automate a search for the simpler kinds, like those based on equilateral triangles and right triangles.

(Please open the following images in a new window if they fail to animate)

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

A hexagon can be divided into six equilateral triangles. An equilateral triangle can be divided into a hexagon and three more equilateral triangles. These simple rules, applied again and again, can be used to create fractals, or shapes that echo themselves on smaller and smaller scales.

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

An Adventure in Multidimensional Space: The Art and Geometry of Polygons, Polyhedra, and Polytopes, Koji Miyazaki (Wiley-Interscience 1987)

An Adventure in Multidimensional Space: The Art and Geometry of Polygons, Polyhedra, and Polytopes, Koji Miyazaki (Wiley-Interscience 1987)

Two, three, four – or rather, two, three, ∞. Polygons are closed shapes in two dimensions (e.g., the square), polyhedra closed shapes in three dimensions (the cube), and polytopes closed shapes in four or more (the hypercube). You could spend a lifetime exploring any one of these geometries, but unless you take psychedelic drugs or brain-modification becomes much more advanced, you’ll be able to see only two of them: the geometries of polygons and polyhedra. Polytopes are beyond imagining but you can glimpse their shadows here – literally, because we can represent polytopes by the shadows they cast in 3-space or by the shadows of their shadows in 2-space.

A four-dimensional shape in two dimensions (see Tesseract)

Elsewhere Miyazaki doesn’t have to convey wonder and beauty by shadows: not only is this book full of beautiful shapes, it’s beautifully designed too and the way it alternates black-and-white pages with colour actually increases the power of both. It isn’t restricted to pure mathematics either: Miyazaki also looks at the modern and ancient art and architecture inspired by geometry, and at geometry in nature: the dodecahedral pollen of Gypsophilum elegans (Showy Baby’s-Breath), for example, and the tetrahedral seeds of the Water Chestnut (Trapa spp.), which the Japanese spies and assassins called the ninja used as natural caltrops. A regular tetrahedron always lies on a flat surface with a vertex facing directly upward, and when a pursued ninja scattered the sharply pointed tetrahedral seeds of the Water Chestnut, they were regular enough to injure “the soles of feet of his pursuers”.

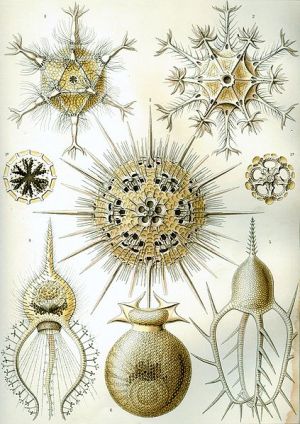

Polyhedral plankton by Ernst Haeckel

The slightly odd English there is another example of what I like about this book, because it proves the parochialism of language and the universality of mathematics. Miyazaki’s mathematics, as far as I can tell, is flawless, like that of many other Japanese mathematicians, but his self-translated English occasionally isn’t. Japanese mathematics was highly developed before Japan fell under strong Western influence. It would continue to develop if the West disappeared tomorrow. Language is something we have to absorb intuitively from the particular culture we’re born into, but mathematics is learnt and isn’t tied to any particular culture. That’s why it’s accessible in the same way to minds everywhere in the world. Miyazaki’s pictures and prose are an extended proof of all that, and the book is actually more valuable because it was written by a Japanese speaker. I think it’s probably more attractively designed for the same reason: the skill with which the pictures have been selected and laid out reflects something characteristically Japanese. Elegance and simplicity perhaps sum it up, and elegance and simplicity are central to mathematics and some of the greatest art.

Another four-dimensional shape in two dimensions (see 120-cell)

Fractals are shapes that contain copies of themselves on smaller and smaller scales. There are many of them in nature: ferns, trees, frost-flowers, ice-floes, clouds and lungs, for example. Fractals are also easy to create on a computer, because you all need do is take a single rule and repeat it at smaller and smaller scales. One of the simplest fractals follows this rule:

1. Take a line of length l and find the midpoint.

2. Erect a new line of length l x lm on the midpoint at right angles.

3. Repeat with each of the four new lines (i.e., the two halves of the original line and the two sides of the line erected at right angles).

When lm = 1/3, the fractal looks like this:

(Please open image in a new window if it fails to animate)

When lm = 1/2, the fractal is less interesting:

But you can adjust rule 2 like this:

2. Erect a new line of length l x lm x lm1 on the midpoint at right angles.

When lm1 = 1, 0.99, 0.98, 0.97…, this is what happens:

The fractals resemble frost-flowers on a windowpane or ice-floes on a bay or lake. You can randomize the adjustments and angles to make the resemblance even stronger:

Ice floes (see Owen Kanzler)

Frost on window (see Kenneth G. Libbrecht)

The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry, David Wells (1991)

The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry, David Wells (1991)

Mathematics is an ocean in which a child can paddle and an elephant can swim. Or a whale, indeed. This book, a sequel to Wells’ excellent Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Mathematics, is suitable for both paddlers and plungers. Plumbers, even, because you can dive into some very deep mathematics here.

Far too deep for me, I have to admit, but I can wade a little way into the shallows and enjoy looking further out at what I don’t understand, because the advantage of geometry over number theory is that it can appeal to the eye even when it baffles the brain. If this book is more expensive than its prequel, that’s because it needs to be. It’s a paperback, but a large one, to accommodate the illustrations.

Fortunately, plenty of them appeal to the eye without baffling the brain, like the absurdly simple yet mindstretching Koch snowflake. Take a triangle and divide each side into thirds. Erect another triangle on each middle third. Take each new line of the shape and do the same: divide into thirds, erect another triangle on the middle third. Then repeat. And repeat. For ever.

A Koch snowflake (from Wikipedia)

The result is a shape with a finite area enclosed by an infinite perimeter, and it is in fact a very early example of a fractal. Early in this case means it was invented in 1907, but many of the other beautiful shapes and theorems in this book stretch back much further: through Étienne Pascal and his oddly organic limaçon (which looks like a kidney) to the ancient Greeks and beyond. Some, on the other hand, are very modern, and this book was out-of-date on the day it was printed. Despite the thousands of years devoted by mathematicians to shapes and the relationship between them, new discoveries are being made all the time. Knots have probably been tied by human beings for as long as human beings have existed, but we’ve only now started to classify them properly and even find new uses for them in biology and physics.

Which is not to say knots are not included here, because they are. But even the older geometry Wells looks at would be enough to keep amateur and recreational mathematicians happy for years, proving, re-creating, and generalizing as they work their way through variations on all manner of trigonomic, topological, and tessellatory themes.

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

• Poulet’s Propeller — discussion of Wells’ Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers (1986)

Imagine four mice sitting on the corners of a square. Each mouse begins to run towards its clockwise neighbour. What happens? This:

The mice spiral to the centre and meet, creating what are called pursuit curves. Now imagine eight mice on a square, four sitting on the corners, four sitting on the midpoints of the sides. Each mouse begins to run towards its clockwise neighbour. Now what happens? This:

But what happens if each of the eight mice begins to run towards its neighbour-but-one? Or its neighbour-but-two? And so on. The curves begin to get more complex:

(Please open the following image in a new window if it fails to animate.)

You can also make the mice run at different speeds or towards neighbours displaced by different amounts. As these variables change, so do the patterns traced by the mice:

• Continue reading Persecution Complexified

How many blows does it take to demolish a wall with a hammer? It depends on the wall and the hammer, of course. If the wall is reality and the hammer is mathematics, you can do it in three blows, like this:

α’. Σημεῖόν ἐστιν, οὗ μέρος οὐθέν.

β’. Γραμμὴ δὲ μῆκος ἀπλατές.

γ’. Γραμμῆς δὲ πέρατα σημεῖα.1. A point is that of which there is no part.

2. A line is a length without breadth.

3. The extremities of a line are points.

That is the astonishing, world-shattering opening in one of the strangest – and sanest – books ever written. It’s twenty-three centuries old, was written by an Alexandrian mathematician called Euclid (fl. 300 B.C.), and has been pored over by everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Bertrand Russell by way of Edna St. Vincent Millay. Its title is highly appropriate: Στοιχεῖα, or Elements. Physical reality is composed of chemical elements; mathematical reality is composed of logical elements. The second reality is much bigger – infinitely bigger, in fact. In his Elements, Euclid slipped the bonds of time, space and matter by demolishing the walls of reality with a mathematical hammer and escaping into a world of pure abstraction.

• Continue reading Neuclid on the Block