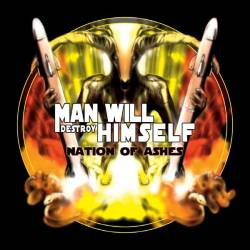

Man Will Destroy Himself, Nation of Ashes (2007)

Man Will Destroy Himself, Nation of Ashes (2007)

I’ve enjoyed this album a lot. It’s short, sharp and psycho-sonically stimulating. It could be called sonic-ironic too. Hardcore, in the guitar sense, is an accelerated and intensified form of punk that first appeared in the late 1980s. It was then an extreme, bleeding-edge – and bleeding-ear – form of music. But now it has three decades of tradition behind it. One of the men who first championed it, the BBC D.J. John Peel (1939-2004), would be seventy-four if he were still alive today. This is from Peel’s auto/biography, Margrave of the Marshes (2004), which was begun by him but completed by his wife Sheila after he died of a heart-attack in Peru:

William [one of Peel’s sons] and I [his wife writes] went regularly with John to gigs that Extreme Noise Terror and Napalm Death played together at the Caribbean Centre in Ipswich. They were grimy, chaotic affairs attended largely by crusties wearing layers of shredded denim and dreadlocks thick as rope. The moshpit was like an initiation ritual – if you could make it out of there in one piece, you knew you could survive anything life had to throw at you. People would stagger out with nosebleeds, clutching their heads, complaining of double vision, drenched in sweat. And yet a good-natured atmosphere prevailed somehow. William, who was around thirteen at the time, took one look at these crusties, who mostly shunned bathing or showering, and decided that this was the musical sub-genre to which he wanted to pledge undying allegiance. His karate teacher attended the reggae nights upstairs at the Caribbean Centre, and would say to William on the way out, “What are you doing listening to that?” (Op. cit., pg. 387-8)

That extract sums up the music well: hardcore is adolescent and part of its early appeal was its ability to shock your parents and conventional society. Okay, the adolescent William Peel was attending Extreme Noise Terror gigs actually with his parents, but then John Peel was a permanent adolescent and the music didn’t appeal to the karate teacher. Before long, William Peel probably did something his father never did, namely begin to grow up. He would then have lost interest in hardcore. Or grindcore, as Sheila Peel calls it. I don’t think E.N.T. were grindcore (and neither do they, apparently) and I don’t think Napalm Death belong with E.N.T. or with Man Will Destroy Himself. For one thing, Napalm Death are crap. For another, they are, or became, much more metal and lost the grimy authenticity of E.N.T. and M.W.D.H.

Grime is authentic, after all: you’re closer to reality when you’re dirty and smelly and living in a squat, far from the nine-to-five conformity of deluded mainstream society. Or are you? In fact, the crusties – named from the crustiness of their unwashed skin and hair – could not have existed without the generous benefit-systems of Western Europe. Crusties sneered at straights – and lived off the taxes of straights. They bemoaned the brutal military-industrial complex – and were kept safe by it from a communist system that would not have tolerated their rebellion for a second. And, of course, they were using electricity to create and record their music. Not to mention benefitting from the transport network for food, the sewage network for hygiene, and the generally law-abiding, relatively uncorrupt societies that surrounded them and without which their “lifestyle” would have been impossible or unsustainable. If crusty political ideas had been realized – or are realized, because they’re alive and well in the Occupy movement – even crusties might begin to see that Western society was rather more complex and benign than they recognized.

But recognizing the complexity and benignity would get in the way of the self-righteousness that is another and essential part of hardcore’s adolescent appeal. You have to strip down your music to get the exciting speed and you have to strip down your ideas to get the exciting sneer. The first track on this album, “Subdivide”, begins with a sample from the end of the film Planet of the Apes (1968), when Charlton Heston learns, in a particularly dramatic and memorable way, where he has been all the time and what man has done with his super-sized brain. “Goddamn you all to Hell!” he cries – and the music swells up and screams off in that exciting, but by now very familiar, hardcore way. It’s an effective opening, but it reminds me of the term used of art by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World (1931): “emotional engineering”. The sample relies for its power on listeners’ previous knowledge of the film. Man has indeed destroyed himself – but in a science-fiction universe. The sample is effective, but insincere. Heston is acting and so, I feel, are M.W.D.H. The theme of nuclear armageddon was very well-trodden well before the ’noughties, when this album was released: Planet of the Apes appeared in 1968 and is based on a book published in 1963. Extreme Noise Terror were railing against the arms-trade from the beginning and E.N.T. have been assaulting ears, offending noses, and straining their throats for a long time now. Which is sonic-ironic: M.W.D.H. could never shock E.N.T. with their music, even though E.N.T. are probably old enough to be their dads.

Global warming, the apocalyptic theme now occupying the progressive community, isn’t so much fun to scream about: it’s slower and less obviously an act of malevolent free-will. But what about the much bigger threats posed not by man but by Mother Nature, with things like asteroid-strikes and mega-volcanoes? Well, hardcore bands have never worked themselves into self-righteous frenzies about those. How can you be self-righteous about billions of people dying if no human agency is involved? If we’re wiped out by an asteroid or a mega-volcano, it will be, at worst, a sin of omission. We could have spent more money researching the threat and inventing ways to prevent or avoid it. We’ve not been wiped out like that yet, but the threats remain and I think we should spend more money watching the skies, for example. But it’s difficult to get emotional about it: there are no self-righteous thrills to be found in nearby asteroids. Nuclear arsenals are different: men made those and men may use them. So you can get emotional about the threat. The strong sensations of hardcore aren’t supplied by just the speed and volume: the self-righteousness and sanctimony are important too. That’s why M.W.D.H. use that sample from Planet of the Apes and put nuclear missiles on the front cover of this album.

I don’t know whether they scream about global warming too, because I can’t understand the lyrics and haven’t found them on the web yet. The final track, “M.O.A.B.”, is presumably about the mega-munition called the “Mother Of All Bombs” by the U.S. military. Whether or not that bomb is the subject, it’s surprising how quickly you reach “M.O.A.B.”: this album whirls by and can seem even shorter than its actual running-time of twenty minutes. Hardcore is headlong, like sheets and shards of metal being blown along by a hurricane. And metal is a word that comes to mind a lot as you listen to this album. The sounds are metallic in an almost literal sense: strong but flexible, meaty but malleable. Nation of Ashes sounds like a sonic factory taking the raw ore of volume and hammering, twisting, and rolling it into shape. That’s appropriate for a form of music that depends on an advanced technological civilization, though it’s sonic-ironic because the music is being used to criticize that civilization. But Nation of Ashes also sounds metallic in a more strictly musical sense. As I’ve said, M.W.D.H. and E.N.T. aren’t metal bands like Napalm Death, but heavy metal does influence the sound of hardcore. There are throbbing, thundering passages between the headlong charges on this album, but that variety increases the power of the music. And has been doing so on hundreds of albums for thousands of days. So, as M.W.D.H.’s music pounds, listeners can ponder things like authenticity and originality.

I’ve certainly pondered my own originality while writing this review. I’m pleased with the title of the review – “Guitardämmerung” – but I’ve found from a web-search that it’s been used before. Other minds have worked like mine, noting the similarity between “guitar” and Götter. The point of a pun is to distort language and create a new sensation from something familiar. That’s also what punk did to rock music, and what hardcore did to punk: they were distortions for new sensations. Sometimes musical distortion is inadvertent: new forms of music, like new forms of life, can arise when there’s a mistake in copying. Or when the technology of the art does undesigned and originally unwanted things, like causing feedback. An accidental thing like that can then become something pursued and valued in its own right. Hardcore is about distortion in lots of ways: it uses distorted guitars and voices to protest about the distortion of society and justice. But this album isn’t distorted in one way: it adheres faithfully to the hardcore recipe first laid down in the late 1980s. So that’s sonic-ironic again.

“Guitardämmerung” also blends ideas in the way that hardcore blends punk and heavy metal. Götterdämmerung means “Twilight of the Gods” and refers to the cataclysmic end of the world in Norse mythology. Man Will Destroy Himself use electric guitars to create music about cataclysm and apocalypse, but are we now in the final stages of guitar-based music? Will hardcore, heavy metal, and other forms of rock exist much longer? I don’t think they will. There are cataclysms of various kinds ahead: political, social, scientific, and technological. The political and social cataclysms probably won’t be those foreseen by the self-righteous and sanctimonious crusty community (crummunity?). And that community may realize that it’s been working for political and social cataclysm in a lot of ways, rather than against it. The scientific and technological cataclysms will be more powerful and long-lasting in their effects – assuming science and technology survive what is ahead in politics and sociology. I don’t think the Deus Ex Machina, the electronically enhanced superhuman now in preparation, will be interested in loud guitars. But I’m not superhuman, or properly grown-up, and I am still interested in loud guitars. Although the music is quite different, this album makes me nostalgic – or prostalgic – in a similar way to the mediaeval ballads on Music of the Crusades. That music was traditional, and so, sonic-ironically, is hardcore, three decades after it first appeared. Hardcore expresses ugly emotions in an ugly way, but it’s still human. And Man is indeed about to be Destroyed.

Nation of Ashes is available for free at Last.fm

Elsewhere other-engageable:

• Musings on Music