Echinops sphaerocephalus, or Great Globe Thistle

Echinops sphaerocephalus, or Great Globe Thistle

Challenger chopped and changed. That is to say, in one important respect, Arthur Conan Doyle’s character Professor Challenger lacked continuity. His philosophical views weren’t consistent. At one time he espoused materialism, at another he opposed it. He espoused it in “The Land of Mist” (1927):

“Don’t tell me, Daddy, that you with all your complex brain and wonderful self are a thing with no more life hereafter than a broken clock!”

“Four buckets of water and a bagful of salts,” said Challenger as he smilingly detached his daughter’s grip. “That’s your daddy, my lass, and you may as well reconcile your mind to it.”

But earlier, in “The Poison Belt” (1913), he had opposed it:

“No, Summerlee, I will have none of your materialism, for I, at least, am too great a thing to end in mere physical constituents, a packet of salts and three bucketfuls of water. Here ― here” ― and he beat his great head with his huge, hairy fist ― “there is something which uses matter, but is not of it ― something which might destroy death, but which death can never destroy.”

That story was published just over a century ago, but Challenger’s boast has not been vindicated in the meantime. So far as science can see, matter rules mind, not vice versa. Conan Doyle thought the same as the earlier Challenger, but Conan Doyle’s rich and teeming brain seems to have ended in “mere physical constituents”. To all appearances, when the organization of his brain broke down, so did his consciousness. And that concluded the cycle described by A.E. Housman in “Poem XXXII” of A Shropshire Lad (1896):

From far, from eve and morning

And yon twelve-winded sky,

The stuff of life to knit me

Blew hither: here am I.Now – for a breath I tarry

Nor yet disperse apart –

Take my hand quick and tell me,

What have you in your heart.Speak now, and I will answer;

How shall I help you, say;

Ere to the wind’s twelve quarters

I take my endless way. (ASL, XXXII)

Continue reading This Mortal Doyle…

“Exchange rate behaves like particles in a molecular fluid” — ScienceDaily, 13/iii/2014.

“Epitaxial mismatches in the lattices of nickelate ultra-thin films can be used to tune the energetic landscape of Mott materials and thereby control conductor/insulator transitions.” — On the road to Mottronics, ScienceDaily, 24/ii/2014.

The Neutrino Hunters: The Chase for the Ghost Particle and the Secrets of the Universe, Ray Jayawardhana (Oneworld 2013)

The Neutrino Hunters: The Chase for the Ghost Particle and the Secrets of the Universe, Ray Jayawardhana (Oneworld 2013)

An easy read on a difficult topic: Ray Jayawardhana takes some complicated ideas and makes them a pleasure to absorb. Humans have only recently discovered neutrinos, but neutrinos have always known us from the inside:

…about a hundred trillion neutrinos produced in the nuclear furnace at the Sun’s core pass through your body every second of the day and night, yet they do no harm and leave no trace. During your entire lifetime, perhaps one neutrino will interact with an atom in your body. Neutrinos travel right through the Earth unhindered, like bullets cutting through a fog. (ch. 1, “The Hunt Heats Up”, pg. 9)

In a way, “ghost particle” is a misnomer: to neutrinos, we are the ghosts, because they pass through all solid matter almost as though it’s not there:

Neutrinos are elementary particles, just like electrons that buzz around atomic nuclei or quarks that combine to make protons and neutrons. They are fundamental building blocks of matter, but they don’t remain trapped inside atoms. Also unlike their subatomic cousins, neutrinos carry no electric charge, have a tiny mass and hardly ever interact with other particles. A typical neutrino can travel through a light-year’s worth of lead without interacting with any atoms. (ch. 1, pg. 7)

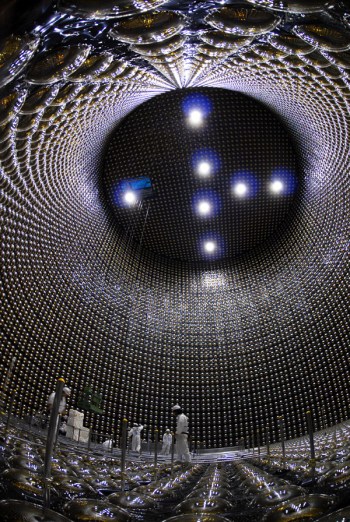

That’s a lot of lead, but a little of neutrino. With a different ratio – a lot less matter and a lot more neutrino – it’s possible to detect them on earth. Because so many are passing through the earth at any moment, a large piece of matter watched for long enough will eventually catch a ghost. So neutrino-hunters sink optical sensors into the transparent ice of the Antarctic and fill huge tanks with carbon tetrachloride or water. Then they wait:

Every once in a while, a solar neutrino would collide with an electron in the water and propel it forward, like a billiard ball that’s hit head-on. The fast-moving electron would create an electromagnetic “wake”, or cone of light, along its path. The resulting pale blue radiation is called “Cherenkov radiation”, after the Russian physicist Pavel Cherenkov, who investigated the phenomenon. Phototubes lining the inside walls of the tank would register each light flash and reveal an electron’s interaction with a neutrino. The Kamiokande provided two extra bits of information to researchers: from the direction of the light cone scientists would infer the direction of the incoming neutrino and from its intensity they could determine the neutrino’s energy. (ch. 4, “Sun Underground”, pg. 95)

That’s a description of a neutrino-hunt in “3,000 tons of pure water” in a mine “150 miles west of Tokyo”: big brains around the world are obsessed with the “little neutral one”. That’s what “neutrino” means in Italian, because the particle was named by the physicist Enrico Fermi (1901-54) after the original proposal, “neutron”, was taken over by another, and much bigger, particle with no electric charge. Fermi was one of the greatest physicists of all time and oversaw the first “controlled nuclear chain reaction” at the University of Chicago in 1942. That is, he helped build the first nuclear reactor. Like the sun, reactors are rich sources of neutrinos and because neutrinos pass easily through any form of shielding, a reactor can’t be hidden from a neutrino-detector. Nor can a supernova: one of the most interesting sections of the book discusses the way exploding stars flood the universe with a lot of light and a lot more neutrinos:

Alex Friedland of the Los Alamos National Laboratory explained that a supernova is in essence a “neutrino bomb”, since the explosion releases a truly staggering number – some 10^58, or ten billion trillion trillion trillion trillion – of these particles. … In fact, the energy emitted in the form of neutrinos within a few seconds is several hundred times what the Sun emits in the form of photons over its entire lifetime of nearly 10 billion years. What’s more, during the supernova explosion, 99 percent of the precursor star’s gravitational binding energy goes into the neutrinos of all flavors, while barely half a percent appears as visible light. (ch. 6, “Exploding Star”, pg. 125)

That light is remarkably bright, but it can be blocked by interstellar dust. The neutrinos can’t, so they’re a way to detect supernovae that are otherwise invisible. However, Supernova 1987A was highly visible: a lot of photons were captured by a lot of telescopes when it flared in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Nearly four hours before that, a few neutrino-detectors had captured far fewer neutrinos:

Detecting a grand total of two dozen particles may not sound like much to crow about. But the significance of these two dozen neutrino events is underlined by the fact that they have been the subject of hundreds of scientific papers over the years. Supernova 1987A was the first time that we had observed neutrinos coming from an astronomical source other than the Sun. (ch. 6, pg. 124)

The timing of the two dozen was very important: it came before the visible explosion and “meant that astrophysicists like Bahcall and his colleagues were right about what happened during a supernova explosion” (pg. 123). That’s John Bahcall (1931-2005), an American who wanted to be a rabbi but ended up a physicist after taking a science course during his philosophy degree at Berkeley. He had predicted how many solar neutrinos his colleague Raymond Davis (1914-2006) should detect interacting with atoms in a giant tank of “dry-cleaning fluid”, as carbon tetrachloride is also known. But Davis found “only a third as many as Bahcall’s model calculation predicted” (ch. 4, pg. 90). Was Davis missing some? Was Bahcall’s model wrong? The answer would take decades to arrive, as Davis refined his apparatus and Bahcall re-checked his calculations. This book is about several kinds of interaction: between neutrinos and atoms, between theory and experiment, between mathematics and matter. Neutrinos were predicted with maths before they were detected in matter. The Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli (1900-58) produced the prediction; Davis and others did the detecting.

The Super-Kamiokande neutrino-cathedral (click for larger image)

Pauli was famously witty; another big brain in the book, the Englishman Paul Dirac (1902-84), was famously taciturn. Big brains are often strange ones too. That’s part of why they’re attracted to the very strange world of atomic physics. Jayawardhana also discusses the Italian physicist Ettore Majorana (1906-?1938), who disappeared at the age of thirty-two, and his colleague Bruno Pontecorvo (1913-93), who defected to the Soviet Union. Neutrinos are fascinating and so are the humans who have hunted for them. So is the history that surrounded them. Quantum physics was convulsing science at the same time as communism and Nazism were convulsing Europe. As the Danish physicist Niels Bohr (1885-1962) said: “Anyone who is not shocked by quantum theory has not understood it.” Modern physicists have been called a new priesthood, devoted to lofty and remote ideas incomprehensible and irrelevant to ordinary people. But ordinary people fund the devices the priests build to pursue their ideas with. And some of the neutrino-detectors pictured here are as huge and awe-inspiring as cathedrals. Some might say they’re as futile as cathedrals too. But if understanding the universe isn’t enough in itself, there may be practical uses for neutrinos on the way. At present, we have to communicate over the earth’s surface; a beam of neutrinos can travel right through the earth.

The universe is also a dangerous place: some scientists theorized that the neutrino deficit in Ray Davis’s experiments meant the sun was about to go nova. It wasn’t, but neutrinos may help the human race spot other dangers and exploit new opportunities. We still know only a fraction of what’s out there and the ghost particle is a messenger from the heart not only of supernovae and the sun, but also of the earth itself. There’s radioactivity deep in the earth, so there are neutrinos streaming upward. As methods of detecting them get better, we’ll understand the interior of the earth better. But Jayawardhana doesn’t discuss another possibility: that we might even discover advanced life down there, living under huge pressures at very high temperatures, as Arthur C. Clarke suggested in his short-story “The Fires Within” (1949).

Clarke also suggested that life could exist inside the sun. There’s presently no way of testing his ideas, but neutrinos may carry even more secrets than standard science has guessed. Either way, I think Clarke would have enjoyed this book and perhaps Jayawardhana, who’s of Sri Lankan origin, was influenced by him. Jayawardhana’s writing certainly reminds me of Clarke’s writing. It’s clear, enthusiastic and a pleasure to read, wearing its learning lightly and carrying you easily over vast stretches of space and time. The Neutrino Hunters is an excellent introduction to the hunters, the hunted and the history, with a good glossary and index too.

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

• Think Ink – Review of 50 Quantum Physics Ideas You Really Need to Know

What a Plant Knows: A Field Guide to the Senses of Your Garden – and Beyond, Daniel Chamovitz (Oneworld 2012)

What a Plant Knows: A Field Guide to the Senses of Your Garden – and Beyond, Daniel Chamovitz (Oneworld 2012)

This is a brief but burgeoning book, covering a lot of science and a lot of scientific history. Plants stay in one place and don’t seem to suffer pain or discomfort, so they’re good experimental subjects, particularly for introverts. That’s why Charles Darwin devoted even more time to plants than he did to worms and barnacles. Chamovitz describes Darwin’s ingenious experiments and the even more ingenious experiments of the researchers that followed him. Over millions of years the world has set problems of survival for plants; in solving these problems, plants have set puzzles for scientists. How do plants know when to flower and prepare for winter? How do they resist attacks by insects? Or prey on insects? Or invite visits from pollinators? And how do they communicate with each other? The answers aren’t just chemical: they’re electrical too, as research on the world’s most famous carnivorous plant has proved:

Alexander Volkov and his colleagues at Oakwood University in Alabama first demonstrated that it is indeed electricity that causes the Venus flytrap to close. To test the model, they rigged up very fine electrodes and applied an electrical current to the open lobes of the trap. This made the trap close without any direct touch to its trigger hairs … (ch. 6, “What A Plant Remembers”, pp. 147-8)

Acoustics is also at work in the plant kingdom:

In a process known as buzz pollination, bumblebees stimulate a flower to release its pollen by rapidly vibrating their wing muscles without actually flapping their wings, leading to a high-frequency vibration. … In a similar vein, Roman Zweifel and Fabienne Zeugin from the University of Bern in Switzerland have reported ultrasonic vibrations emanating from pine and oak trees during a drought. These vibrations result from changes in the water content of the water-transporting xylem vessels. While these sounds are passive results of physical forces (in the same way that a rock crashing off a cliff makes a noise), perhaps these ultrasonic vibrations are used as a signal by other trees to prepare for dry conditions. (ch. 4, “What A Plant Hears”, pg. 107-8)

All of this is mathematical: a plant is a mechanism that processes not just sun, water and carbon-dioxide, but information from its environment too. But then sun, water and CO2 are all part of that information: sunlight signals plants as well as sustaining them. Its strength and duration are cues for the seasons and time of the day. So is its colour:

By the time John F. Kennedy was elected president, Warren L. Butler and his colleagues had demonstrated that a single photoreceptor in plants was responsible for both the red and far-red effects. They called this receptor “phytochrome”, meaning “plant colour”. In its simplest model, phytochrome is a light-activated switch. Red light activates phytochrome, turning it into a form primed to receive far-red light. Far-red light inactivates phytochrome, turning it into a form primed to receive red light. Ecologically, this makes a lot of sense. In nature, the last light a plant sees at the end of the day is far-red, and this signifies to the plant that it should “turn-off”. In the morning it sees red light and it wakes up. In this way a plant measures how long ago it last saw red light and adjusts its growth accordingly. (ch. 1, “What A Plant Sees”, pg. 21-2)

There’s an obvious analogy with a computer automatically turning itself off and on, which would make phytochrome and its associated chemicals a kind of hardware created by the software of the genes. Plants share some of that software with human beings: in one fascinating section, Chamovitz discusses the links between healthy plants and sick people:

The arabidopsis [A. thaliana, mustard plant] genome contains BRCA, CFTR, and several hundred other genes associated with human disease or impairment because they are essential for basic cellular biology. These important genes had already evolved 1.5 billion years ago in the single-celled organism that was the common evolutionary ancestor to both plants and animals. (ch. 4, “What A Plant Hears”, pg. 105)

What a Plant Knows stimulates human minds as it discusses plant senses. It’s one of the best briefest, or briefest best, books on science I’ve ever read, packing a lot of history and scientific information into six chapters. Plants don’t move much, but they’re a very lively topic and botany is a good way to understand and appreciate biology and scientific research better.

The Spark of Life: Electricity in the Human Body, Frances Ashcroft (Penguin 2013)

The Spark of Life: Electricity in the Human Body, Frances Ashcroft (Penguin 2013)

“Electricity in the Human Body” is the subtitle of this book. Make that the goat, frog, eel, shark, torpedo-ray, snake, platypus, spiny anteater, sooty shearwater and fruit-fly body too. And if Venus flytraps, maize and algae have bodies, throw them in next. Frances Ashcroft gives you a bargeload of buzz for your buck, a shedload of shock for your shekel: The Spark of Life describes the use of electricity by many different forms of life. But it discusses death a lot too, from lightning-strikes and electric chairs to heart-attacks and toxicology. Poisons can be a cheap and highly effective way of interfering with the electro-chemistry of the body:

The importance of sodium and potassium channels in generating the nerve impulse is demonstrated by the fact that a vast array of poisons from spiders, shellfish, sea anemones, frogs, snakes, scorpions and many other exotic creatures interact with these channels and thereby modify the function of nerve and muscle. … The tetrodotoxin contained in the liver and other tissues of this fish [the fugu or puffer-fish, Takifugu spp., Lagocephalus spp., etc] is a potent blocker of the sodium channels found in your nerves and skeletal muscles. It causes numbness and tingling of the lips and mouth within as little as thirty minutes … This sensation of “pins and needles” spreads rapidly to the face and neck, moves onto the fingers and toes, and is then followed by gradual paralysis of the skeletal muscles … Ultimately the respiratory muscles are paralysed, which can be fatal. The heart is not affected, as it has a different kind of sodium channel that is far less sensitive to tetrodotoxin. The toxin is also unable to cross the blood-brain barrier so that, rather horrifyingly, although unable to move and near death, the patient remains conscious. (ch. 3, “Acting on Impulse”, pp. 69-70)

In short, fugu-poisoning is the opposite of electrocution: it’s the absence rather than the excess of electricity that kills its victims. Those “channels” are a reminder that electro-chemistry could also be called electro-mechanics: unlike an electricity-filled computer, an electricity-filled body has moving parts – and in more ways than one. Our muscles move because ions move in and out of our cells. This means that a body has to be wet inside, not dry like a computer, but it’s easy to imagine a human brain controlling a robotic body. But would a brain still be conscious if it became metal-and-plastic too? Perhaps a brain has to be both soggy and sparky to be conscious.

The electrical nature of the brain certainly seems important, though that may be a superstitious conclusion. Electricity is a mysterious phenomenon and so is consciousness, so they seem to go together well. Ashcroft writes a lot about the sense-organs and the data they supply to the brain, but like all scientists she cannot explain how those data are turned into conscious experience as the maths-engine of the brain applies its neuro-functions and neuro-algorithms. However, she does suggest ways in which our consciousness might be expanded in future. Humans have colour vision, based on the three types of cone-cells in our eyes:

Most mammals, such as cats and dogs, have only two types of cone photopigment and so see only a limited range of colour … Other animals live in a world entirely without colour. But humans should not be too complacent, for we are far from having the best colour vision in the animal world and lag far behind the mantis shrimp, which enjoys ten or more different visual pigments. Even tropical fish possess four or five types of cones. (ch. 9, “The Doors of Perception”, pg. 199)

Bio-engineering may one day sharpen and extend all our senses, from sight and hearing to touch, taste and smell. It may also give us new senses, like the ability to form sound-pictures like bats and detect infra-red like pit-vipers. And why not X-rays and radio-waves too? It’s an exciting prospect, but in a sense it won’t be anything new: our new senses, like our old ones, will depend on nerve-impulses and the way they’re mashed and mathed in that handful of “electrified clay” known as the brain.

“Electrified clay” is Shelley’s phrase: like his wife Mary, he was fascinated by the early electric experiments of the Italian scientists Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta. Mary turned her fascination into a book called Frankenstein (1818) and her invention is part of the scientific history in this book. The story of bio-electricity is still going strong: there are electric mysteries in all kinds of bodies waiting to be solved. Maybe consciousness is one of them. And if science proves unable to crack consciousness, it’s certainly able to expand it. Reading this book is one way to experience the mind-expanding powers of science, but seeing like a mantis shrimp would be good too.

One of the most powerful images in this book is also one of the most understated. It’s an artist’s impression of a dim star seen over the curve of a dwarf-planet called Sedna. The star is a G-type called Sol. We on Earth know it better as the sun. Sedna is a satellite of the sun too, but it’s much, much further out than we are. It takes 12,000 years to complete a single orbit and its surface is a biophobic -240°C. It’s so distant that sunrise is star-rise and it wasn’t discovered until 2003. But the sun’s gravity still keeps it in place: one of the weakest forces in nature is one of the most influential. That’s one important message in an understated, crypto-Lovecraftian image.

Sedna has been there, creeping around its dim mother-star, since long before man evolved. It will still be there long after man disappears, voluntarily or otherwise. This frozen dwarf is a good symbol of the vastness of the universe and its apparent indifference to life. We don’t seem to interest the universe at all, but the universe certainly interests us. Wonders of the Solar System is a good introduction to our tiny corner of it, describing some fundamentals of astronomy with the help of spectacular photographs and well-designed illustrations. You can learn how fusion powers the sun, how Mars lost its atmosphere and how there might be life beneath the frozen surface of Jupiter’s satellite Europa. The text is simple, but not simplistic, though I think the big name on the cover did little of the writing: this book is probably much more Cohen than Cox. Either way, I enjoyed reading the words and not just looking at the pictures, all the way from star-dim Sedna (pp. 26-7) to “Scars on Mars” (pp. 220-1) by way of “The most violent place in the solar system” (pp. 198-9), a.k.a. Jupiter’s gravity-flexed, volcano-pocked satellite Io.

Pockmarked moon — the Galilean satellite Io

Everything described out there is linked to something down here, because that’s how it was done in the television series. Linking the sky with the earth allowed the BBC to film the genial and photogenic physicist Brian Cox in various exotic settings: Hawaii, India, East Africa, Iceland and so on. I’ve not seen any of Cox’s TV-work, but he seems an effective popularizer of science. And the pretty-boy shots here add anthropology to the astronomy. What is the scientific point of Cox striding away in an artistic blur over the Sahara desert (pg. 103), staring soulfully into the distance near the Iguaçu Falls on the Brazilian-Argentine border (pg. 37) or gazing down into the Grand Canyon, hips slung, hands in pockets (pg. 163)? There isn’t a scientific point: the photos are there for his fans, particularly his female ones. He’s a sci-celeb, a geek with chic, and we’re supposed to see the sky through Bri’s eyes.

But he’s also a liberal working for the Bolshevik Broadcasting Corporation, so he’ll be happy with the prominent photo early on: Brian holding protective glasses over the eyes of a dusky-skinned child during a solar eclipse in India. The same simul-scribes’ Wonders of Life (Collins 2013), another book-of-the-BBC-series, opens with a similarly allophilic allophoto: a dusky-skinned Mexican crowned in monarch butterflies. This is narcissistic and patronizing, but the readiness of whites to “Embrace the Other” helps explain science, because science involves looking away from the self, the tribe and the quotidian quest for status and survival. Of course, Cox and Cohen would gasp with horror at the idea of racial differences explaining big things like science and politics. Cox would be sincere in his horror. I’m not so sure about Cohen.

But there are wonders within us as well as without us and though you won’t hear about them on the BBC, the tsunami of HBD, or research into human bio-diversity, is now rolling ashore. It will sweep away almost all of Cox’s and Cohen’s politics, but leave most of their science intact. It isn’t a coincidence that the rings of Saturn were discovered by the Italian Galileo and explained by the Dutchman Huygens and the Italian Cassini, or that the photos of Saturn here were taken by a space-probe launched by white Americans. But the United States has much less money now for space exploration. That’s explained by race too: as the US looks less like its founders, it looks less like a First World nation too. It’s fun to see the world through Bri’s eyes, but he’s careful not to look at everything that’s out there.

In “Hymn to Herm”, I wrote about a religion based on √2, or the square root of two, the number that, multiplied by itself, equals 2. In the religion, neophytes learn the mystery and majesty of this momentous number when they try to calculate its exact value. The calculation involves adding and subtracting fractions based on powers of two. The first step is this: 1 x 1 = 1. So that’s too small. Add 1/2^1 = ½ and re-multiply: 1½ x 1½ = 2¼. Too big. So subtract 1/2^2 = ¼, and re-multiply. 1¼ x 1¼ = 1+9/16. Too small. Add 1/8 and re-multiply. 1+3/8 x 1+3/8 = 1+57/64. Too small again. Add 1/16 and re-multiply. And so on.

In effect, what the neophytes are doing is calculate the digits of √2 in binary, or base two. When the multiplication is too small, put a 1; when it’s too big, put a 0. Like this:

1 x 1 = 1 < 2, so √2 ≈ 1·…

1½ x 1½ = 2¼ > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·0…

1¼ x 1¼ = 1+9/16 < 2, so √2 ≈ 1·01…

(1+3/8) x (1+3/8) = 1+57/64 < 2, so √2 ≈ 1·011…

(1+7/16) x (1+7/16) = 2+17/256 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·0110…

(1+13/32) x (1+13/32) = 1+1001/1024 < 2, so √2 ≈ 1.01101…

(1+27/64) x (1+27/64) = 2+89/4096 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1.011010…

(1+53/128) x (1+53/128) = 1+16377/16384 < 2, so √2 ≈ 1·0110101…

(1+107/256) x (1+107/256) = 2+697/65536 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·01101010…

(1+213/512) x (1+213/512) = 2+1337/262144 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·011010100…

(1+425/1024) x (1+425/1024) = 2+2449/1048576 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·0110101000…

(1+849/2048) x (1+849/2048) = 2+4001/4194304 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·01101010000…

(1+1697/4096) x (1+1697/4096) = 2+4417/16777216 > 2, so √2 ≈ 1·011010100000…

(1+3393/8192) x (1+3393/8192) = 1+67103361/67108864 < 2, so √2 ≈ 1·0110101000001…

Mathematically naïve neophytes, seeing the process miss 2 by smaller and smaller amounts on either side, might imagine that eventually the exact root will appear and the calculations end. But they would be wrong. They could work a year or a million years: they would never calculate the exact square root of two. There is no ratio of whole numbers, a/b, such that a^2/b^2 = 2. In other words, √2 is an irrational number, or number that can’t be represented as a ratio of integers (please see appendix for the proof).

This discovery, made by Greek mathematicians more than two millennia ago, is both mind-boggling and world-shattering. In fact, it’s mind-boggling in part because it’s world-shattering. √2 shatters the world because the world is too small to contain it: in the words of the Cult of Infinite Hermaphrodites, “Were the sky all parchment, the seas all ink, and gulls all plucked for quills”, the square root of two could not be recorded in full. This is far more certain than tomorrow’s sunrise, because predicting tomorrow’s sunrise depends on fallible scientific reasoning from incomplete knowledge. Proving the irrationality of √2 depends on infallible mathematical reasoning.

At least, it’s as close to infallible as human beings can get. But that’s another part of what is mind-boggling about √2. A finite, feeble human being, with a speck of soon-decaying brain, can prove the existence of things larger than the universe. A few binary digits of √2 are shown above. Here are a few more:

1· 0110101000001001111001100110011111110011101111001100100100001000 1011001011111011000100110110011011101010100101010111110100111110 0011101011011110110000010111010100010010011101110101000010011001 1101101000101111010110010000101100000110011001110011001000101010 1001010111111001000001100000100001110101011100010100010110000111 0101000101100011111111001101111110111001000001111011011001110010 0001111011101001010100001011110010000111001110001111011010010100 1111000000001001000011100110110001111011111101000100111011010001 1010010001000000010111010000111010000101010111100011111010011100 1010011000001011001110001100000000100011011110000110011011110111 1001010101100011011110010010001000101101000100001000101100010100 1000110000010101011110001110010001011110111110001001110001100111 1000110110101011010100010100011100010111011011111101001110111001 1001011001010100110001101000011001100011111001111001000010011011 1110101001011110001001000001111100000110110111001011000001011101 1101010101001001010000010001001100100000100000011001010010010101 0000001001110010100101010110110110110001111110100001110111111011 1110100110100111010000000101100111010111100100100111110000011000 1000010011001001101101010111100110101010010100010110110010100011 0111000110011110011010000011011011011111000001000110110110001110 0000001000001001101110000000001111111100011001000110101001011110 0110011001010100101111010011111011110111101101000011110101111111 1110110101000011011111000111111110010100010001000010011000001111 1011110101000000110001001000001111101111010101010000001110000101 1000001111111001011110111011110101000101111011111011100001100110 0011000100000111000101000101110101011111111010111110011101100101 1010010010011110100101001110110001111111010110010111000100000101 1111101111111100001011100001111110100111011000111110111100000001 1111001101011001100111001000001011110010111111100101000000001011 1000010010001100111100001011110100100101001010101110000001000110 1011111110011111000111101111011110010100011111010100011001110110 1001101011111000110000010100101111001100011001111100011111000010 1001000010111110011101101001001010011011000001010111100011000001 0000101101011000010011111011010010000111110010010010010011110101 1011011100011111100000101101110011010010100100000011011000001001 1101111011101000100100010010100110000011110101001110101010101101 0000111011101010001100100001111101110100100010011111010001101010 0111111010010000001100001011111000100000111110110111011010010100 1110111110110101100011001001100110000100110011011101011100001010 0001110110101001000001000101110000111101000100110011101000000110 1000010000100011110101101110001110000011000000111101100100000001 1011101010011101101000110100011101100110100001000111100101101100 0101110011010101100101110010110111000000111111110011010101000000 1100001101000001001010010100001011010110010000000110000100000001 1110111101101111110001101101111010010001000101001010001010110100 1111001001001000110001101000100111000110000000001011101101000000 1010100010110101011010110000010000011111110101011101111001101110 0000110111010000110001100110110101001000001100011111111001111111 1111111101010111010101111110010001110001000010011000000011001101 1011110101011100001001101000010010000101110110100101111010010001 1011001111100010111100100000010110110111001001110010010110111001 0111000111010110000010100001111110001000100011110000100010100000 1010011011100001000000001100110011101101110000101100111001011011 1101100110001010111011100111000111100100001011100010011010001101 0011011110100110000001110010111100100010000000100011010001100001 0011111111111100001000100100010100110100001110011110101010010111 1010100110011001101101101100100111100011110011100111000111111001 0100110101100000100100101010110011100001001000001010101110001110 0101010100001110000011010101010100010001011010001000011000110001 0111011110001100111101100000001101010000110100000010111111101000 0101111100101001111011001000101111100101110001110010101110000000 0111101011110101011101110001101110000010010110110011000010100000 1110011110000011011101101010100100011100000010001100011010100111 1111000011111000111100110010001110110011011000101000000111010010 0010010101101000100111000000101101011010100000100000010001111101 1011100110001001111101100011101010001010011001001110100001010001 1001101111000000110100001100000111100010001000101000000001001000 0100110110010100111101001111100110111011001111010100101100110001 1101010010001001110101110101001000110001101101011100011000110011 1100010010000000110010010110101111100101010010011011111101011101 1001011001100111100010110100110100101100010011011101101010000110 0111101111011000111001001000000000101001111111101010100011001000 0001011100110101011001111100001010111010001111010011110011101001 1101111111100000101111010001101101001101110101110111000100010111 1000000001010111101101101001010110110111111010101111000110110000 0101110000100010110010001101010111111110111010111101000001110111 1111111011001001011011011011100011110111011110001111110000011100 0010101110111011110011100001101101001001111010111111010110101111 0100010001100000100010000010100101011000101011011101000000011100 1010011111110001101101101011110000001011011111101100000110111100 0110111000001010011011101101101111000110011111111000010110110010 0111010011100000100001100001101100111010000100110111010101110001 1011000101100101010010011000011100111101001000010001110001101010 1010111001101001110110000000000111100101011110010100010001011011 1100011000001010001111100000101001001111110110001001011010001110 1011011110010100101111011100011100000010110101101001010001011101 1010100101001011000001001010010001000000110010101011110010010100 0011100001111100001111010010011011111101000011110011101111101000 1010111101100011000001011010010100111010000101110111001010001000 1010110010100001001111111011010000000110110010011000001010010001 0101110110000011101110100000110100110101010110001101100000011101 1101000100010101100111101001011001000011111010101010001001111110 1011011101110101011110100010000001010010100101110101101101101111 0100101010001000100111100011110100001001001010111011000111000110 1000010101001000000011011100001011101001100110010100011110110011 0111001011011110110110100000010111100010000110010010111110010101 1011000110111001001001100101000100101011010000000100110000110011 0001100000011101011...

The distribution of 1’s and 0’s seems effectively random, as though the God of Mathematics were endlessly tossing a coin, putting 1 for heads, 0 for tails. Yet √2 is the opposite of a random number. Change a single digit anywhere and it ceases to be √2. Every 1 and every 0 is rigidly determined by “unalterable law”. So are the position and magnitude of the digits of √2 in every other base. Here, for example, is √2 in base 4:

1· 112220021321212133303233030210020230233230103121232222111133 103320322313230011311010213131100212131220233112100230012121 303020222211133210012002013111...

Another word for base-4 is DNA: genes are in fact written in a base-4 code based on the chemicals guanine, adenine, thymine and cytosine, or G, A, T, C for short. If the digits of √2 are truly random, in the statistical sense, then all genomes, actual and potential, occur somewhere along its length: yours, mine, the Emperor Heliogabalus’s, Bilbo Baggins’, the sabre-toothed tiger’s, the dodo’s, and so on. But almost all the “DNA” of √2 in base-4 will be meaningless: although √2 is the opposite of random, it is effectively a typing chimpanzee. Or a typing worm – a type-worm. √2 is like an endless worm that types out its own segments on a typewriter with two keys (for binary numbers) or four keys (for quaternary numbers) or ten keys (for decimal numbers) and so on.

But √2 doesn’t just encode the genomes of individual people, animals and plants: it encodes everything they do throughout their lives. In fact, it encodes the entire universe. And perhaps the universe is √2 or some number like it. Perhaps, in some sense, everything exists within the digits of an irrational number, or a sufficiently large rational number. If so, then √2 has become aware of itself through human beings: the World as Worm has bitten its own tail.

Appendix: Proof of the irrationality of √2

1. Suppose that there is some ratio, a/b, such that

2. a and b have no factors in common and

3. a^2/b^2 = 2.

4. It follows that a^2 = 2b^2.

5. Therefore a is even and there is some number, c, such that 2c = a.

6. Substituting c in #4, we derive (2c)^2 = 4c^2 = 2b^2.

7. Therefore 2c^2 = b^2 and b is also even.

8. But #7 contradicts #2 and the supposition that a and b have no factors in common.

9. Therefore, by reductio ad absurdum, there is no ratio, a/b, such that a^2/b^2 = 2. Q.E.D.

A story is stranger than a star. Stronger too. What do I mean? I mean that the story has more secrets than a star and holds its secrets more tightly. A full scientific description of a star is easier than a full scientific description of a story. Stars are much more primitive, much closer to the fundamentals of the universe. They’re huge and impressive, but they’re relatively simple things: giant spheres of flaming gas. Mathematically speaking, they’re more compressible: you have to put fewer numbers into fewer formulae to model their behaviour. A universe with just stars in it isn’t very complex, as you would expect from the evolution of our own universe. There were stars in it long before there were stories.

A universe with stories in it, by contrast, is definitely complex. This is because stories depend on language and language is the scientific mother-lode, the most difficult and important problem of all. Or rather, the human brain is. The human brain understands a lot about stars, despite their distance, but relatively little about itself, despite brains being right on the spot. Consciousness is a tough nut to crack, for example. Perhaps it’s uncrackable. Language looks easier, but linguistics is still more like stamp-collecting than science. We can describe the structure of language in detail – use labels like “pluperfect subjunctive”, “synecdoche”, “bilabial fricative” and so on – but we don’t know how that structure is instantiated in the brain or where language came from. How did it evolve? How is it coded in the human genome? How does meaning get into and out of sounds and shapes, into and out of speech and writing? These are big, important and very interesting questions, but we’ve barely begun to answer them.

Distribution of dental fricatives and the O blood-group in Europe (from David Crystal’s Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language)

But certain things seem clear already. Language-genes must differ in important ways between different groups, influencing their linguistic skills and their preferences in phonetics and grammar. For example, there are some interesting correlations between blood-groups and use of dental fricatives in Europe. The invention of writing has exerted evolutionary pressures in Europe and Asia in ways it hasn’t in Africa, Australasia and the Americas. Glossogenetics, or the study of language and genes, will find important differences between races and within them, running parallel with differences in psychology and physiology. Language is a human universal, but that doesn’t mean one set of identical genes underlies the linguistic behaviour of all human groups. Skin, bones and blood are human universals too, but they differ between groups for genetic reasons.

Understanding the evolution and effects of these genetic differences is ultimately a mathematical exercise, and understanding language will be too. So will understanding the brain. For one thing, the brain must, at bottom, be a maths-engine or math-engine: a mechanism receiving, processing and sending information according to rules. But that’s a bit like saying fish are wet. Fish can’t escape water and human beings can’t escape mathematics. Nothing can: to exist is to stand in relation to other entities, to influence and be influenced by them, and mathematics is about that inter-play of entities. Or rather, that inter-play is Mathematics, with a big “M”, and nothing escapes it. Human beings have invented a way of modelling that fundamental micro- and macroscopic inter-play, which is mathematics with a small “m”. When they use this model, human beings can make mistakes. But when they do go wrong, they can do so in ways detectable to other human beings using the same model:

In 1853 William Shanks published his calculations of π to 707 decimal places. He used the same formula as [John] Machin and calculated in the process several logarithms to 137 decimal places, and the exact value of 2^721. A Victorian commentator asserted: “These tremendous stretches of calculation… prove more than the capacity of this or that computer for labor and accuracy; they show that there is in the community an increase in skill and courage…”

Augustus de Morgan thought he saw something else in Shanks’s labours. The digit 7 appeared suspiciously less often than the other digits, only 44 times against an average expected frequency of 61 for each digit. De Morgan calculated that the odds against such a low frequency were 45 to 1. De Morgan, or rather William Shanks, was wrong. In 1945, using a desk calculator, Ferguson found that Shanks had made an error; his calculation was wrong from place 528 onwards. Shanks, fortunately, was long dead. (The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers, 1986, David Wells, entry for π, pg. 51)

Unlike theology or politics, mathematics is not merely self-correcting, but multiply so: there are different routes to the same truths and different ways of testing a result. Science too is self-correcting and can test its results by different means, partly because science is a mathematical activity and partly because it is studying a mathematical artifact: the gigantic structure of space, matter and energy known as the Universe. Some scientists and philosophers have puzzled over what the physicist Eugene Wigner (1902-95) called “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”. In his essay on the topic, Wigner tried to make two points:

The first point is that the enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious and that there is no rational explanation for it. Second, it is just this uncanny usefulness of mathematical concepts that raises the question of the uniqueness of our physical theories. (Op. cit., in Communications in Pure and Applied Mathematics, vol. 13, No. I, February 1960)

I disagree with Wigner: it is not mysterious or uncanny and there is a rational explanation for it. The “effectiveness” of small-m maths for scientists is just as reasonable as the effectiveness of fins for fish or of wings for birds. The sea is water and the sky is air. The universe contains both sea and sky: and the universe is maths. Fins and wings are mechanisms that allow fish and birds to operate effectively in their water- and air-filled environments. Maths is a mechanism that allows scientists to operate effectively in their maths-filled environment. Scientists have, in a sense, evolved towards using maths just as fish and birds have evolved towards using fins and wings. Men have always used language to model the universe, but language is not “unreasonably effective” for understanding the universe. It isn’t effective at all.

It is effective, however, in manipulating and controlling other human beings, which explains its importance in politics and theology. In politics, language is used to manipulate; in science, language is used to explain. That is why mathematics is so important in science and so carefully avoided in politics. And in certain academic disciplines. But the paradox is that physics is much more intellectually demanding than, say, literary theory because the raw stuff of physics is actually much simpler than literature. To understand the paradox, imagine that two kinds of boulder are strewn on a plain. One kind is huge and made of black granite. The other kind is relatively small and made of chalk. Two tribes of academic live on the plain, one devoted to studying the black granite boulders, the other devoted to studying the chalk boulders.

The granite academics, being unable to lift or cut into their boulders, will have no need of physical strength or tool-making ability. Instead, they will justify their existence by sitting on their boulders and telling stories about them or describing their bumps and contours in minute detail. The chalk academics, by contrast, will be lifting and cutting into their boulders and will know far more about them. So the chalk academics will need physical strength and tool-making ability. In other words, physics, being inherently simpler than literature, is within the grasp of a sufficiently powerful human intellect in a way literature is not. Appreciating literature depends on intuition rather than intellect. And so strong intellects are able to lift and cut into the problems of physics as they aren’t able to lift and cut into the problems of literature, because the problems of literature depend on consciousness and on the hugely complex mechanisms of language, society and psychology.

Intuition is extremely powerful, but isn’t under conscious control like intellect and isn’t transparent to consciousness in the same way. In the fullest sense, it includes the senses, but who can control his own vision and hearing or understand how they turn the raw stuff of the sense-organs into the magic tapestry of conscious experience? Flickering nerve impulses create a world of sight, sound, scent, taste and touch and human beings are able to turn that world into the symbols of language, then extract it again from the symbols. This linguifaction is a far more complex process than the ignifaction that drives a star. At present it’s beyond the grasp of our intellects, so the people who study it don’t need and don’t build intellectual muscle in the way that physicists do.

Or one could say that literature is at a higher level of physics. In theory, it is ultimately and entirely reducible to physics, but the mathematics governing its emergence from physics are complex and not well-understood. It’s like the difference between a caterpillar and a butterfly. They are two aspects of one creature, but it’s difficult to understand how one becomes the other, as a caterpillar dissolves into chemical soup inside a chrysalis and turns into something entirely different in appearance and behaviour. Modelling the behaviour of a caterpillar is simpler than modelling the behaviour of a butterfly. A caterpillar’s brain has less to cope with than a butterfly’s. Caterpillars crawl and butterflies fly. Caterpillars eat and butterflies mate. And so on.

Stars can be compared to caterpillars, stories to butterflies. It’s easier to explain stars than to explain stories. And one of the things we don’t understand about stories is how we understand stories.

2:1 Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem, 2:2 Saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? for we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him. 2:3 When Herod the king had heard these things, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. 2:4 And when he had gathered all the chief priests and scribes of the people together, he demanded of them where Christ should be born. 2:5 And they said unto him, In Bethlehem of Judaea: for thus it is written by the prophet, 2:6 And thou Bethlehem, in the land of Juda, art not the least among the princes of Juda: for out of thee shall come a Governor, that shall rule my people Israel. 2:7 Then Herod, when he had privily called the wise men, enquired of them diligently what time the star appeared. 2:8 And he sent them to Bethlehem, and said, Go and search diligently for the young child; and when ye have found him, bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also. 2:9 When they had heard the king, they departed; and, lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. 2:10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy. 2:11 And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense and myrrh. – From The Gospel According to Saint Matthew.