Collins Complete Guide to British Coastal Wildlife, Paul Sterry and Andrew Cleave (HarperCollins 2012)

Living by a river is good, but living by the sea is better. This means that the ideal might be Innsmouth:

The harbour, long clogged with sand, was enclosed by an ancient stone breakwater; on which I could begin to discern the minute forms of a few seated fishermen, and at whose end were what looked like the foundations of a bygone lighthouse. A sandy tongue had formed inside this barrier and upon it I saw a few decrepit cabins, moored dories, and scattered lobster-pots. The only deep water seemed to be where the river poured out past the belfried structure and turned southward to join the ocean at the breakwater’s end. (“The Shadow Over Innsmouth”, 1936)

Lovecraft would certainly have liked Collins Complete Guide to British Coastal Wildlife, a solid photographic guide to the flora and fauna of the British coast. There are some very Lovecraftian species here, both floral and faunal. Among the plants there’s sea-holly, Eryngium maritimum, a blue-grey shingle-dweller with gothically spiky and veined leaves. It has its own specialized parasite, Orobanche minor ssp. maritima, “an exclusively coastal sub-species” of common broomrape (pg. 94). Among the Lovecraftian animals there are the cephalopods (octopuses and squids), echinoderms (sea-urchins and starfish) and cnidarians (jellyfish and sea-anemones), but also the greater and lesser weever, Trachinus draco and Echiichthys vipera, which are “notorious fish, capable of inflicting a painful sting to a bather’s foot” (pg. 278).

But the strangest and most wonderful creatures in the book might be the sea-slugs and sea-hares, which are brightly coloured or enigmatically mottled, with surreal knobs, furs and “rhinophores”, or head tentacles. If LSD took organic form, it might look like a sea-slug.

Greilada elegans, “orange with blue spots”,

Flabellina pedata, “purple body and pinkish-red cerata”,

Catriona gymnata, “swollen, orange and white-tipped”, resemble the larvae of some eldritch interstellar race, destined to grow great and eat worlds (pp. 218-222 – “cerata” are “dorsal projections”). As it is, they stay tiny: the orange-clubbed sea-slug,

Limacia clavigera, gets to 15mm on a diet of bryozoans, the miniature coral-like animals that are Lovecraftian in a different way. That “Limacia”, from the Latin

limax, meaning “slug”, is a reminder that sea-slugs have an accurate common name, unlike Montagu’s sea snail,

Liparis montagui, and the sea scorpion,

Taurulus bubalis, which are both fish, and sea ivory,

Ramalina siliquosa, which is a lichen. This book includes a land slug too, the great black,

Arion ater, but it has none of the charm or beauty of its marine relatives.

Arion ater is included here because it’s “particularly common on coastal cliffs, paths and dunes” (pg. 239). The land snails that accompany it have charm, like the looping snail, Truncatella subcylindrica, and the wrinkled snail, Candidula intersecta, but they don’t have the beauty and variety of marine shell-dwellers, from the limpets, scallops and cockles to the wentletraps, cowries and whelks. And the violet snail, Jacintha jacintha, which rides the open ocean on a “‘float’ of mucus-trapped bubbles” as it feeds on the by-the-wind sailor, Velella velella. Layfolk would say that Velella and its relative Physalia physalis, the Portuguese man-o’-war, are jellyfish, but they’re actually “pelagic hydroids”. And Physalia is a colony of animals, not a single animal.

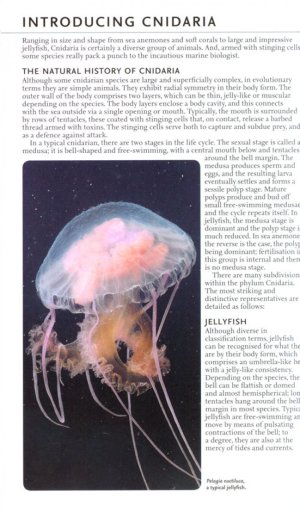

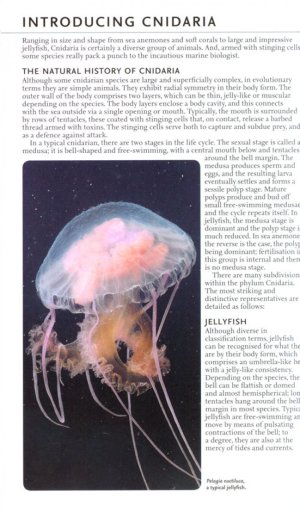

Sample page #1

Both jellyfish and hydroids are related to sea-anemones and corals: they’re all classified as cnidaria, from the Greek κνιδη,

knidē, meaning “nettle”. In short: they all sting. Some swim and sway too: the colours, patterns and sinuosity of the cnidaria are seductively strange. There are strawberry, snakelocks, gem, jewel, fountain and plumose anemones, for example:

Actinia fragacea,

Anemonia viridis,

Aulactinia verrucosa,

Corynactis viridis,

Sargartiogeton laceratus and

Metridium senile. The tentacles of the last-named look like a glossy head of white hair and the snakelocks anemone sometimes has green tentacles with purple tips.

After the cnidaria come the annelids, or segmented worms, which can be beautiful or repulsive, mundane or surreal, free-living or sessile. For example, the scaleworms are “unusual-looking polychaete worms whose dorsal surface is mostly or entirely covered with overlapping scales” (pg. 129). They’re reminiscent of the sea-slugs, though less strange and more subdued. But segmented worms gave rise to the wild variety of the crustaceans, including crabs, sea-slaters, lobsters and even barnacles, one species of which is a parasite: Sacculina carcini forms a “branching network” (pg. 178) within the body of a crab, particularly the green shore crab, Carcinus maenas. You would never guess that it was a barnacle and you might not guess that an infected crab was infected, because the yellow “reproductive structure” of the barnacle looks as though it belongs to the crab itself.

Sample page #2

And there’s a photograph here to prove it. In fact, there are two: one in the barnacle’s own entry, the other in the entry for the green shore crab. I like the way the guide gives extra information like that. In the entries for sea-lavender,

Limonium vulgare, and thrift,

Armeria maritima, there are small photographs of insects that feed “only” or “almost exclusively” on these plants: the plume moth

Agditis bennetii, with very narrow wings, and the more conventional moth

Polymixis xanthomista (pg. 90), respectively. Those insects, with Fisher’s estuarine moth,

Gortyna borelii, and the Sand Dart,

Agrotis ripae, are stranded in the wild-flower section, as though they’ve been deposited there by a stray current. The fiery clearwing moth,

Pyropteron chrysidiformis, is stranded in another way: in Britain, it’s “entirely restricted to stretches of grassy undercliff on the south coast of Kent”. It looks like a wasp wearing make-up. The scaly cricket,

Pseudomogoplistes vincentae, isn’t attractive but is romantic in a similar way: it’s “confined to a handful of coastal shingle beaches in Britain and the Channel Islands” (pg. 17).

Also confined is the bracket fungus

Phellinus hippophaeicola, which is “found only” on the trunks of sea buckthorn,

Hippophae rhamnoides (pg. 54). Its photograph appears with its host, but the full fungus section is only one page anyway. It includes the “unmistakable” dune stinkhorn,

Phallus hadriani, whose scientific name means “Hadrian’s dick”. It’s “restricted to dunes and associated with Marram” grass (pg. 50). But fungi flourish best away from the coast. Not that “flourish” is the right word, because fungi don’t flower. Nor do seaweeds, the giant algae that have to survive both battering by the waves and exposure to sun and wind. They cope by being tough: leathery or horny or chalky or coralline. And though their colours are limited mostly to green, brown and red, their geometry is very varied: leafy, membranous, thong-like, ribbon-like, whip-like, fan-like, feather-like, even globular: punctured ball weed,

Leathesia difformis, and oyster thief,

Colpomenia peregrina, for example. The book doesn’t explain why “oyster thief” is called that. Landlady’s wig,

Desmarestia aculeata, red rags,

Dilsea carnosa, and bladder wrack,

Fucus vesiculous, are self-explanatory.

And there’s a bluntness to names like wrack, kelp and the various weeds – bean-weed, bead-weed, wire-weed – that go well with the rough, tough life these plants lead. That’s why rainbow wrack, Cystoseria tamariscifolia, sounds so odd. But it lives up to its name: it’s “bushy and iridescent blue-green underwater” (pg. 36).

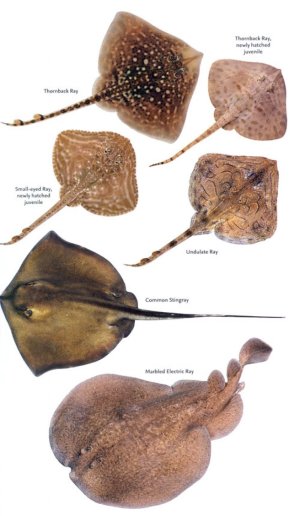

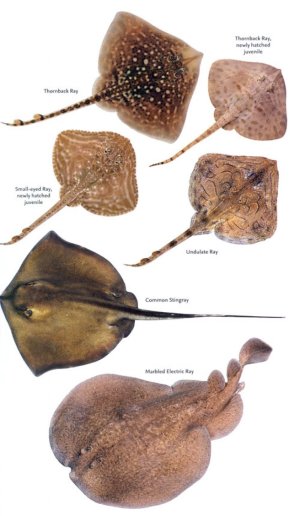

Seaweeds are at the beginning of the book; birds, fish and mammals are at the end. After the strangeness, surreality and beauty of some of the plants and invertebrates, the higher animals can seem almost mundane. Evolution hasn’t found as many spinal solutions as non-spinal, because the invertebrates have been around much longer. Among the vertebrates, it’s been working longest on the fish, so the variety of shapes is greatest there: rays and flounders, lampreys and eels, sea-horses and pipe-fish, the giant sun-fish and the largest animal native to Britain, the basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus. Some of the names seem ancient and long-evolved too: saithe, pogge, goldsinny, weever, dab, goby, blenny, shanny and brill. The last-named, Scophthalmus rhombus, is a flatfish with a typically ugly head. As the book notes: “In their early stages, they resemble conventional species. But during their development the head shape distorts so that, although they lie and swim on their sides, both eyes are on top” (pg. 257).

The rays aren’t distorted like that: they lie on their bellies, not on their sides, so their eyes don’t look distorted. Evolution has taken two different routes to the same ecological niche, the sea-floor. Camouflage is useful there, so both rays and flatfish have beautiful patterns: specklings, mottlings and spots. Other fish are colourful, but British fish can’t match the rainbow variety of fish in the tropics. Nor can British birds. The kingfisher, Alcedo atthis, is a rare exception and it “favours fresh waters”, except in winter (pg. 328). Truly coastal birds can be hard to tell apart: the knot, Calidris canutus, and the Sanderling, Calidris alba, are not as distinctive as their common names. Nor are the whimbrel, Numenius phaeopus, and the curlew, Numenius arquata. Both have long down-curved beaks and streaked, “grey-brown plumage” (pg. 342). But the whimbrel is smaller and rarer.

The gulls and terns can also be hard to tell apart, as can the skuas that prey on and parasitize them. “Skua”, which comes from Old Norse skúfr, is a good name for a gangster-like bird. I prefer “gull” in what is probably its original form, the Welsh gŵylan. The French mouette, for small gulls, and goéland, for large ones, are also good, and some French bird-names are used in English: avocet, plover and guillemot, for example. “Plover” is from Latin pluvia, “rain”, but the reference is “unexplained”, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. The reference of “ruff” might seem to be obvious: the male ruff, Philomachus pugnax, has a ruff of feathers in the breeding season, like a kind of gladiatorial costume: its scientific name literally means “the pugnacious lover-of-fighting”. But the female of this species is called a reeve, so perhaps ruffs have nothing to do with ruffs: the feminine form, “apparently made … by a vowel change (cf. fox vixen) suggests that [ruff] is an older word and separate” (OED).

This book uses “ruff” for both sexes: it doesn’t have space to chase etymology and give more than brief details of the hundreds of species it covers. The final species are the mammals and the final mammals are the ones that have returned to the sea: whales, dolphins and seals. After them comes a brief section on “The Strandline”:

A beach marks the zone where land meets sea. It is also where detached and floating matter is washed up and deposited by the tides, typically in well-defined lines. During periods of spring tides, debris is pushed to the top of the shore. But with approaching neap tides, tide extremes diminish and the high-tide mark drops; the result is a series of different strandlines on the shore. The strandline is a great place for the marine naturalist to explore and find unexpected delights washed up from the depths. But it is also home to a range of specialised animals that exploit the rich supply of organic matter created by decomposing seaweeds and marine creatures. (pg. 368)

Those specialised animals – sand-hoppers, kelp-flies and so on – have been covered earlier in the book, so this section covers things like skeletons, skulls, fossils and egg-cases – the “sea wash balls” laid by whelks and the “mermaid’s purses” laid by rays. Then there are “sea-beans”, tree-seeds that may have “drifted across the Atlantic from the Caribbean or Central America”. At first glance, seaweeds also seem to make a come-back in this section. Not so: a bryozoan branches like a plant but is “actually a colonial animal that lives just offshore attached to shells and stones”. Bryzoans are often washed ashore after storms. One of the commonest is hornwrack, Flustra foliacea, of which “fresh specimens smell like lemon” (pg. 254). When I first noticed that for myself, I thought I was having an olfactory hallucination. That’s the sea for you: always changing, always surprising. This book captures its complexity in 384 well-designed pages full of eye- and brain-candy.

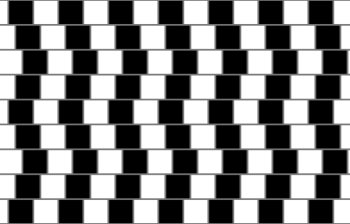

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)