Yale tablet, YBC 7289, c. 1700 BC.

Yale tablet, YBC 7289, c. 1700 BC.

In Boldly Breaking the Boundaries, I looked at the use of squares in what I called over-fractals, or fractals whose sub-divisions reproduce the original shape but appear beyond its boundaries. Now I want to look at over-fractals using triangles. They’re less varied than those involving squares, but still include some interesting shapes. This is the space in which sub-triangles can appear, with the central seeding triangle coloured gray:

Here are some over-fractals based on the pattern above:

In “M.I.P. Trip”, I looked at fractals like this, in which a square is divided repeatedly into a pattern of smaller squares:

As you can see, the sub-squares appear within the bounds of the original square. But what if some of the sub-squares appear beyond the bounds of the original square? Then a new family of fractals is born, the over-fractals:

A roulette is a little wheel or little roller, but it’s much more than a game in a casino. It can also be one of a family of curves created by tracing the path of a point on a rotating circle. Suppose a circle rolls around another circle of the same size. This is the resultant roulette:

The shape is called a cardioid, because it looks like a heart (kardia in Greek). Now here’s a circle with radius r rolling around a circle with radius 2r:

That shape is a nephroid, because it looks like a kidney (nephros in Greek).

This is a circle with radius r rolling around a circle with radius 3r:

The shapes above might be called outer roulettes. But what if a circle rolls inside another circle? Here’s an inner roulette whose radius is three-fifths (0.6) x the radius of its rollee:

The same roulette appears inverted when the inner circle has a radius two-fifths (0.4) x the radius of the rollee:

But what happens when the circle rolling “inside” is larger than the rollee? That is, when the rolling circle is effectively swinging around the rollee, like a bunch of keys being twirled on an index finger? If the rolling radius is 1.5 times larger, the roulette looks like this:

If the rolling radius is 2 times larger, the roulette looks like this:

Here are more outer, inner and over-sized roulettes:

And you can have circles rolling inside circles inside circles:

And here’s another circle-in-a-circle in a circle:

The Latin phrase multum in parvo means “much in little”. It’s a good way of describing the construction of fractals, where the application of very simple rules can produce great complexity and beauty. For example, what could be simpler than dividing a square into smaller squares and discarding some of the smaller squares?

Yet repeated applications of divide-and-discard can produce complexity out of even a 2×2 square. Divide a square into four squares, discard one of the squares, then repeat with the smaller squares, like this:

Increase the sides of the square by a little and you increase the number of fractals by a lot. A 3×3 square yields these fractals:

And the 4×4 and 5×5 fractals yield more:

A regular hexagon can be divided into six equilateral triangles. An equilateral triangle can be divided into three more equilateral triangles and a regular hexagon. If you discard the three triangles and repeat, you create a fractal, like this:

Adjusting the sides of the internal hexagon creates new fractals:

Discarding a hexagon after each subdivision creates new shapes:

And you can start with another regular polygon, divide it into triangles, then proceed with the hexagons:

Papyrocentric Performativity Presents:

• Sky Story – The Cloud Book: How to Understand the Skies, Richard Hamblyn (David & Charles 2008)

• Wine Words – The Oxford Companion to Wine, ed. Janice Robinson (Oxford University Press 2006)

• Nu Worlds – Numericon, Marianne Freiberger and Rachel Thomas (Quercus Editions 2014)

• Thalassobiblion – Ocean: The Definitive Visual Guide, introduction by Fabien Cousteau (Dorling Kindersley 2014) (posted @ Overlord of the Über-Feral)

Or Read a Review at Random: RaRaR

In maths, one thing leads to another. I wondered whether, in a spiral of integers, any number was equal to the digit-sum of the numbers on the route traced by moving to the origin first horizontally, then vertically. To illustrate the procedure, here is a 9×9 integer spiral containing 81 numbers:

| 65 | 64 | 63 | 62 | 61 | 60 | 59 | 58 | 57 | | 66 | 37 | 36 | 35 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 31 | 56 | | 67 | 38 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 30 | 55 | | 68 | 39 | 18 | 05 | 04 | 03 | 12 | 29 | 54 | | 69 | 40 | 19 | 06 | 01 | 02 | 11 | 28 | 53 | | 70 | 41 | 20 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 27 | 52 | | 71 | 42 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 51 | | 72 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 |

Take the number 21, which is three places across and up from the bottom left corner of the spiral. The route to the origin contains the numbers 21, 22, 23, 8 and 1, because first you move right two places, then up two places. And 21 is what I call a route number, because 21 = 3 + 4 + 5 + 8 + 1 = digitsum(21) + digitsum(22) + digitsum(23) + digitsum(8) + digitsum(1). Beside the trivial case of 1, there are two more route numbers in the spiral:

58 = 13 + 14 + 6 + 7 + 7 + 6 + 4 + 1 = digitsum(58) + digitsum(59) + digitsum(60) + digitsum(61) + digitsum(34) + digitsum(15) + digitsum(4) + digitsum(1).

74 = 11 + 12 + 13 + 14 + 10 + 5 + 8 + 1 = digitsum(74) + digitsum(75) + digitsum(76) + digitsum(77) + digitsum(46) + digitsum(23) + digitsum(8) + digitsum(1).

Then I wondered about other possible routes to the origin. Think of the origin as one corner of a rectangle and the number being tested as the diagonal corner. Suppose that you always move away from the starting corner, that is, you always move up or right (or up and left, and so on, depending on where the corners lie). In a x by y rectangle, how many routes are there between the diagonal corners under those conditions?

It’s an interesting question, but first I’ve looked at the simpler case of an n by n square. You can encode each route as a binary number, with 0 representing a vertical move and 1 representing a horizontal move. The problem then becomes equivalent to finding the number of distinct ways you can arrange equal numbers of 1s and 0s. If you use this method, you’ll discover that there are two routes across the 2×2 square, corresponding to the binary numbers 01 and 10:

Across the 3×3 square, there are six routes, corresponding to the binary numbers 0011, 0101, 0110, 1001, 1010 and 1100:

Across the 4×4 square, there are twenty routes:

Across the 5×5 square, there are 70 routes:

Across the 6×6 and 7×7 squares, there are 252 and 924 routes:

After that, the routes quickly increase in number. This is the list for n = 1 to 14:

1, 2, 6, 20, 70, 252, 924, 3432, 12870, 48620, 184756, 705432, 2704156, 10400600… (see A000984 at the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences)

After that you can vary the conditions. What if you can move not just vertically and horizontally, but diagonally, i.e. vertically and horizontally at the same time? Now you can encode the route with a ternary number, or number in base 3, with 0 representing a vertical move, 1 a horizontal move and 2 a diagonal move. As before, there is one route across a 1×1 square, but there are three across a 2×2, corresponding to the ternary numbers 01, 2 and 10:

There are 13 routes across a 3×3 square, corresponding to the ternary numbers 0011, 201, 021, 22, 0101, 210, 1001, 120, 012, 102, 0110, 1010, 1100:

And what about cubes, hypercubes and higher?

“In 1997, Fabrice Bellard announced that the trillionth digit of π, in binary notation, is 1.” — Ian Stewart, The Great Mathematical Problems (2013).

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

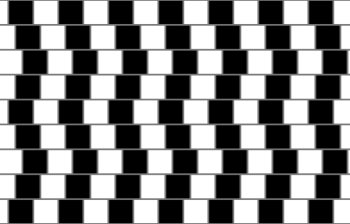

A simple book with some complex illusions. It’s aimed at children but scientists have spent decades understanding how certain arrangements of colour and line fool the eye so powerfully. I particularly like the black-and-white tiger set below a patch of blue on page 60. Stare at the blue “for 15 seconds”, then look quickly at a tiny cross set between the tiger’s eyes and the killer turns colour.

So what’s not there appears to be there, just as, elsewhere, what’s there appears not to be. Straight lines seem curved; large figures seem small; the same colour seems light on the right, dark on the left. There are also some impossible figures, as made famous by M.C. Escher and now studied seriously by geometricians, but the only true art here is a “Face of Fruits” by Arcimboldo. The rest is artful, not art, but it’s interesting to think what Escher might have made of some of the ideas here. Mind is mechanism; mechanism can be fooled. Optical illusions are the most compelling examples, because vision is the most powerful of our senses, but the lesson you learn here is applicable everywhere. This book fools you for fun; others try to fool you for profit. Caveat spectator.

Simple but complex: The café wall illusion