The quickest way to improve your life is to stop watching TV.

• White Dot — the International Campaign against Television

The quickest way to improve your life is to stop watching TV.

• White Dot — the International Campaign against Television

Reading about Searle’s Chinese Room Argument at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, I came across “Leibniz’s Mill” for the first time. At least, I think it was the first time:

It must be confessed, however, that perception, and that which depends upon it, are inexplicable by mechanical causes, that is to say, by figures and motions. Supposing that there were a machine whose structure produced thought, sensation, and perception, we could conceive of it as increased in size with the same proportions until one was able to enter into its interior, as he would into a mill. Now, on going into it he would find only pieces working upon one another, but never would he find anything to explain perception. It is accordingly in the simple substance, and not in the compound nor in a machine that the perception is to be sought. Furthermore, there is nothing besides perceptions and their changes to be found in the simple substance. And it is in these alone that all the internal activities of the simple substance can consist. (Monadology, 1714, section #17)

Andererseits muß man gestehen, daß die Vorstellungen, und Alles, was von ihnen abhängt, aus mechanischen Gründen, dergleichen körperliche Gestalten und Bewegungen sind, unmöglich erklärt werden können. Man stelle sich eine Maschine vor, deren Structur so eingerichtet sei, daß sie zu denken, zu fühlen und überhaupt vorzustellen vermöge und lasse sie unter Beibehaltung derselben Verhältnisse so anwachsen, daß man hinein, wie in das Gebäude einer Mühle eintreten kann. Dies vorausgesetzt, wird man bei Besichtigung des Innern nichts Anderes finden, als etliche Triebwerke, deren eins das andere bewegt, aber gar nichts, was hinreichen würde, den Grund irgend einer Vorstellung abzugeben. Die letztere gehört ausschließlich der einfachen Substanz an, nicht der zusammengesetzten, und dort, nicht hier, muß man sie suchen. Auch sind Vorstellungen und ihre Veränderungen zugleich das Einzige, was man in der einfachen Substanz antrifft. (Monadologie, 1714)

We can see that Leibniz’s argument applies to mechanism in general, not simply to the machines he could conceive in his own day. He’s claiming that consciousness isn’t corporeal. It can’t generated by interacting parts or particles. And intuitively, he seems to be right. How could a machine or mechanism, however complicated, be conscious? Intuition would say that it couldn’t. But is intuition correct? If we examine the brain, we see that consciousness begins with mechanism. Vision and the other senses are certainly electro-chemical processes in the beginning. Perhaps in the end too.

Some puzzles arise if we assume otherwise. If consciousness isn’t mechanistic, how does it interact with mechanism? If it’s immaterial, how does it interact with matter? But those questions go back much further, to Greek atomists like Democritus (c. 460-370 BC):

Δοκεῖ δὲ αὐτῶι τάδε· ἀρχὰς εἶναι τῶν ὅλων ἀτόμους καὶ κενόν, τὰ δ’ἀλλα πάντα νενομίσθαι.

He taught that the first principles of the universe are atoms and void; everything else is merely thought to exist.

Νόμωι (γάρ φησι) γλυκὺ καὶ νόμωι πικρόν, νόμωι θερμόν, νόμωι ψυχρόν, νόμωι χροιή, ἐτεῆι δὲ ἄτομα καὶ κενόν.

By convention sweet is sweet, bitter is bitter, hot is hot, cold is cold, color is color; but in truth there are only atoms and the void. (Democritus at Wikiquote)

Patterns of unconscious matter and energy influence consciousness and are perhaps entirely responsible for it. The patterns are tasteless, soundless, colourless, scentless, neither hot nor cold – in effect, units of information pouring through the circuits of reality. But are qualia computational? I think they are. I don’t think it’s possible to escape matter or mechanism and I certainly don’t think it’s possible to escape mathematics. But someone who thinks it’s possible to escape at least the first two is the Catholic philosopher Edward Feser. I wish I had come across his work a long time ago, because he raises some very interesting questions in a lucid way and confirms the doubts I’ve had for a long time about Richard Dawkins and other new atheists. His essay “Schrödinger, Democritus, and the paradox of materialism” (2009) is a good place to start.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• Double Bubble

• This Mortal Doyle

• The Brain in Pain

• The Brain in Train

When we are conscious of being conscious, what are we consciousness-conscious with? If consciousness is a process in the brain, the process has become aware of itself, but how does it do so? And what purpose does consciousness-of-consciousness serve? Is it an artefact or an instrument? Is it an illusion? A sight or sound or smell is consciousness of a thing-in-itself, but that doesn’t apply here. We aren’t conscious of the thing-in-itself: the brain and its electro-chemistry. We’re conscious of the glitter on the swinging sword, but not the sword or the swing.

We can also be conscious of being conscious of being conscious, but beyond that my head begins to spin. Which brings me to an interesting reminder of how long the puzzle of consciousness has existed in its present form: how do we get from matter to mind? As far as I can see, science understands the material substrate of consciousness – the brain – in greater and greater detail, but is utterly unable to explain how objective matter becomes subjective consciousness. We have not moved an inch towards understanding how quanta become qualia since this was published in 1871:

Were our minds and senses so expanded, strengthened, and illuminated, as to enable us to see and feel the very molecules of the brain; were we capable of following all their motions, all their groupings, all their electric discharges, if such there be; and were we intimately acquainted with the corresponding states of thought and feeling, we should be as far as ever from the solution of the problem, “How are these physical processes connected with the facts of consciousness?” The chasm between the two classes of phenomena would still remain intellectually impassable.

Let the consciousness of love, for example, be associated with a right-handed spiral motion of the molecules of the brain, and the consciousness of hate with a left-handed spiral motion. We should then know, when we love, that the motion is in one direction, and, when we hate, that the motion is in the other; but the “Why?” would remain as unanswerable as before. — John Tyndall, Fragments of Science (1871), viâ Rational Buddhism.

Elsewhere other-posted:

• Double Bubble

• The Brain in Pain

• The Brain in Train

• This Mortal Doyle

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

Eye Bogglers: A Mesmerizing Mass of Amazing Illusions, Gianni A. Sarcone and Marie-Jo Waeber (Carlton Books 2011; paperback 2013)

A simple book with some complex illusions. It’s aimed at children but scientists have spent decades understanding how certain arrangements of colour and line fool the eye so powerfully. I particularly like the black-and-white tiger set below a patch of blue on page 60. Stare at the blue “for 15 seconds”, then look quickly at a tiny cross set between the tiger’s eyes and the killer turns colour.

So what’s not there appears to be there, just as, elsewhere, what’s there appears not to be. Straight lines seem curved; large figures seem small; the same colour seems light on the right, dark on the left. There are also some impossible figures, as made famous by M.C. Escher and now studied seriously by geometricians, but the only true art here is a “Face of Fruits” by Arcimboldo. The rest is artful, not art, but it’s interesting to think what Escher might have made of some of the ideas here. Mind is mechanism; mechanism can be fooled. Optical illusions are the most compelling examples, because vision is the most powerful of our senses, but the lesson you learn here is applicable everywhere. This book fools you for fun; others try to fool you for profit. Caveat spectator.

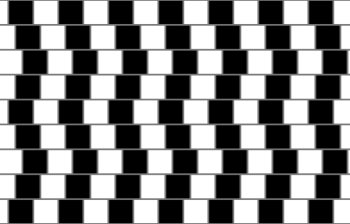

Simple but complex: The café wall illusion

“…par la suggestive lecture d’un ouvrage racontant de lointains voyages…” – J.K. Huysmans, À Rebours (1884).

The language you know best is also the language you know least: your mother tongue, the language you acquired by instinct and speak by intuition. Asking a native speaker to describe English, French or Quechua is rather like asking a fish to describe water. The native speaker, like the fish, knows the answer very intimately, yet in some ways doesn’t know as well as a non-native speaker. In other words, standing outside can help you better understand standing inside: there is good in the gap. What is it like to experience gravity? Like most humans, I’ve known all my life, but I’d know better if I were in orbit or en route to the moon, experiencing the absence of gravity.

And what is it like to be human? We all know and we’ve all read countless stories about other human beings. But in some ways they don’t answer that question as effectively as stories that push humanity to the margins, like Richard Adams’ Watership Down (1972), which is about rabbits, or Isaac Asimov’s The Gods Themselves (also 1972), which is about trisexual aliens in a parallel dimension. There is good in the gap, in stepping outside the familiar and looking back to see the familiar anew.

Continuing reading The Power of Babel…

I hope that nobody thinks I’m being racially prejudiced when I say that, much though I am fascinated by her, I do not find the Anglo-American academic Mikita Brottman physically attractive. It is her mind that has raised my longstanding interest, nothing more.

Honest.

This is because, for me, Ms B is like a mirror that reverses not left and right, but male and female.

Obviously, we’re different in a lot of ways: I don’t smoke and I don’t have any tattoos, for example.

But there are big similarities too.

We were born in the same year (1956) and we were both keyly core contributors to seminal early issues of the transgressive journal Headpress Journal.

And we have various other things in common, like our mutually shared passion for corpse’n’cannibal cinema, our Glaswegian accents and (at different times) our season tickets for Hull Kingston Rovers.

So it is that, looking at Ms B, I have the uncanny experience of seeing myself as I might have been, had I been born female.

But it’s not just uncanny.

It’s horrifying at times too.

Okay, I’m comfortable with the idea that, born female, I would have been less intelligent and more conformist. So I don’t mind that Ms B is a Guardianista. Not particularly. I can face the fact that I would quite likely have been one of them too, as a female.

But there are worse things than being a Guardianista, believe it or not.

Ms B has a PhD in EngLit.

A PhD!

In EngLit.

It’s not at all easy for me to face the fact that I might have had one too, as a female. It really isn’t. But how can I deny it? I might have. That despicable, deplorable, thoroughly disreputable subject might have attracted me. In fact, it would probably have attracted me.

<retch>

But it gets worse still.

Ms B is a psychoanalyst.

A psychoanalyst.

Ach du lieber Gott!

See what I mean by “horrifying”?

I mean, even if I’d been born female I wouldn’t have sunk to such depths, would I? Would I? No, I have to face facts: I might. But I don’t think so. I have a feeling that there’s more to Brotty’s interest in Freud than her gender statusicity and her key commitment to core componency of the counter-cultural community.

But I’d better say no more. Verb sap.

European Reptile and Amphibian Guide, Axel Kwet (New Holland 2009)

European Reptile and Amphibian Guide, Axel Kwet (New Holland 2009)

An attractive book about animals that are mostly attractive, sometimes strange, always interesting. It devotes photographs and descriptive text to all the reptiles and amphibians found in Europe, from tree-frogs to terrapins, from skinks to slow-worms. Some of the salamanders look like heraldic mascots, some of the lizards like enamel jewellery, and some of the toads like sumo wrestlers with exotic skin-diseases. When you leaf through the book, you’ve moving through several kinds of space: geographic and evolutionary, aesthetic and psychological. Europe is a big place and has a lot of reptilian and amphibian variety, including one species of turtle, the loggerhead, Caretta caretta, and one species of chameleon, the Mediterranean, Chamaeleo chamaeleon.

But every species, no matter how dissimilar in size and appearance, has a common ancestor: the tiny crested newt (Triturus cristatus) to the far north-west in Scotland and the two-and-a-half metre whip snake (Dolichophis caspius) to the far south-east in Greece; the sun-loving Hermann’s tortoise (Testudo hermanni), with its sturdy shell, and the pallid and worm-like olm (Proteus anguinus), which lives in “underground streams in limestone karst country along the coast from north-east Italy to Montenegro” (pg. 55). Long-limbed or limbless, sun-loving or sun-shunning, soft-skinned or scaly – they’re all variations on a common theme.

Other snake-like reptiles retain vestiges of the fore-limbs too, like the Italian three-toed skink (Chalcides chalcides). The slow-worm, Anguis fragilis, has lost its limbs entirely, but doesn’t look sinister like a snake and can still blink. Elsewhere, some salamanders have lost not limbs but lungs: the Italian cave salamander, Speleomantes italicus, breathes through its skin and the lining of its mouth. So does Gené’s cave salamander, Speleomantes genei, which is found only on the island of Sardinia. It “emits an aromatic scent when touched” (pg. 54). Toads can emit toxins and snakes can inject venoms: movement in evolutionary space means movement in chemical space, because every alteration in an animal’s appearance and anatomy involves an alteration in the chemicals created by its body. But chemical space is two-fold: genotypic and phenotypic. The genes change and so the products of the genes change. The external appearance of every species is like a bookmark sticking out of the Book of Life, fixing its position in gene-space. You have to open that book to see the full recipe for the animal’s anatomy, physiology and behaviour, though not everything is specified by the genes.

Pleuronectes platessa on the sea-floor

Olm in a Slovenian cave

50 Quantum Physics Ideas You Really Need to Know, Joanne Baker (Quercus 2013)

50 Quantum Physics Ideas You Really Need to Know, Joanne Baker (Quercus 2013)

A very good introduction to a very difficult subject. A very superficial introduction too, because it doesn’t use proper mathematics. If it did, I’d be lost: like most people’s, my maths is far too weak for me to understand quantum physics. Here’s one of the side-quotes that help make this book such an interesting read: “We must be clear that when it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry.”

That’s by the Jewish-Danish physicist Niels Bohr (1885-1962). It applies to quantum physics in general. Without the full maths, you’re peering through a frost-covered window into a sweetshop, you’re not inside sampling the wares. But even without the full maths, the concepts and ideas in this book are still difficult and challenging, from the early puzzles thrown up by the ultra-violet catastrophe to the ingenious experiments that have proved particle-wave duality and action at a distance.

But there’s a paradox here.

Continue reading: Think Ink…

You can stop reading now, if you want. Or can you? Are your decisions really your own, or are you and all other human beings merely spectators in the mind-arena, observing but neither influencing nor initiating what goes on there? Are all your apparent choices in your brain, but out of your hands, made by mechanisms beyond, or below, your conscious control?

In short, do you have free will? This is a big topic – one of the biggest. For me, the three most interesting things in the world are the Problem of Consciousness, the Problem of Existence and the Question of Free Will. I call consciousness and existence problems because I think they’re real. They’re actually there to be investigated and explained. I call free will a question because I don’t think it’s real. I don’t believe that human beings can choose freely or that any possible being, natural or supernatural, can do so. And I don’t believe we truly want free will: it’s an excuse for other things and something we gladly reject in certain circumstances.

Continue reading The Brain in Pain…

“The most merciful thing in the world,” said H.P. Lovecraft, “is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.” Nowadays we can’t correlate all the contents of our hard-drives either. But occasionally bits come together. I’ve had two MP3s sitting on my hard-drive for months: “Drink or Die” by Erotic Support and “Hunter Gatherer” by Swords of Mars. I liked them both a lot, but until recently I didn’t realize that they were by two incarnations of the same Finnish band.

They don’t sound very much alike, after all. But now that I’ve correlated them, they’ve inspired some thoughts on music and mutilation. “Drink or Die” is a dense, fuzzy, leather-lunged rumble-rocker that, like a good Mötley Crüe song, your ears can snort like cocaine. But, unlike Mötley Crüe, the auditory rush lasts the whole song, not just the first half. “Hunter Gatherer” is much more sombre. Erotic Support were “Helsinki beercore”; Swords of Mars are darker, doomier and dirgier. They’ve also got a better name – “Erotic Support” seems to have lost something in translation. Finnish is a long way from English: it’s in a different and unrelated language family, the Finno-Ugric, not the Indo-European. So it lines up with Hungarian and Estonian, not English, German and French. But Erotic Support’s lyrics are good English and “Drink or Die” is a clever title. They’d have been a more interesting band if they’d sung entirely in Finnish, but also less successful, because less accessible to the rest of the world.

Es war einmal eine Königstochter, die ging hinaus in den Wald und setzte sich an einen kühlen Brunnen. Sie hatte eine goldene Kugel, die war ihr liebstes Spielwerk, die warf sie in die Höhe und fing sie wieder in der Luft und hatte ihre Lust daran. Einmal war die Kugel gar hoch geflogen, sie hatte die Hand schon ausgestreckt und die Finger gekrümmt, um sie wieder zufangen, da schlug sie neben vorbei auf die Erde, rollte und rollte und geradezu in das Wasser hinein.

Mieleni minun tekevi, aivoni ajattelevi

lähteäni laulamahan, saa’ani sanelemahan,

sukuvirttä suoltamahan, lajivirttä laulamahan.

Sanat suussani sulavat, puhe’et putoelevat,

kielelleni kerkiävät, hampahilleni hajoovat.Veli kulta, veikkoseni, kaunis kasvinkumppalini!

Lähe nyt kanssa laulamahan, saa kera sanelemahan

yhtehen yhyttyämme, kahta’alta käytyämme!

Harvoin yhtehen yhymme, saamme toinen toisihimme

näillä raukoilla rajoilla, poloisilla Pohjan mailla.

All the same, being inaccessible sometimes helps a band’s appeal to the rest of the world: the mystique of black metal is much stronger in bands that use only Norwegian or one of the other Scandinavian languages. Erotic Support haven’t joined that rebellion against Coca-Colonization and tried to create an indigenous genre. They’re happy to reproduce more or less American music using the more or less American invention known as the electric guitar. But amplified music would have appeared in Europe even if North America had been colonized by the Chinese, so I wonder what rock would sound like if it had evolved in Europe instead. It wouldn’t be called rock, of course, but what other differences would it have? Would it be more sophisticated, for example? I think it would. The success of American exports depends in part on their strong and simple flavours. “Drink or Die” has those flavours: it’s about volume, rhythm and power. It’s full of a certain “drug-addled, crab-infested, tinnitus-nagged spirit” — the “urge to submerge in the raw bedrock viscerality of rock”, as some metaphor-mixing, über-emphasizing idiot once put it (I think it was me).

Erotic Support are “beercore”, remember. Beer marks the brain with hangovers, just as tattoos mark the skin with ink. And just as loud music marks the ears with tinnitus. There are various kinds of self-mutilation in rock and that self-mutilation can have unhealthy motives. It can be an expression of boredom, angst, anomie and self-hatred. Unsurprisingly, Finland has the nineteenth highest suicide rate in the world. Beer, tattoos and tinnitus are part of the louder, dirtier and loutier end of rock: unlike Radiohead or Coldplay, Erotic Support sound like a band with tattoos who are used to hangovers. “Drink or Die” is a joke about exactly that. But what if rock had evolved in a wine-drinking culture? Would it be less of a sado-masochistic ritual, more a refined rite? Maybe not: the god of wine is Dionysos and he was Ho Bromios, the Thunderer. His brother Pan induces panic with loud noises. But black metal looks towards northern paganism: it’s music for pine forests, cold seas and beer-drinkers, not olive groves, warm seas and oenopotes.

Erotic Support don’t create soundscapes for Finland the way black metal creates soundscapes for Norway, but they do create beer-drinkers’ music, so they do express Finnishness to that extent. Swords of Mars, being darker, doomier and dirgier, are moving nearer an indigenous Finnish rock, or an indigenous Scandinavian rock, at least. This may be related to the fact that genes express themselves more strongly as an individual ages: for example, the correlation between the intelligence of parents and their children is strongest when the children are adults. Erotic Support create faster, more aggressive music than Swords of Mars, so it isn’t surprising that they’re the younger version of the same band. In biology, the genotype creates the phenotype: DNA codes for bodies and behaviour. Music is part of what Richard Dawkins calls the “extended phenotype”, like the nest of a bird or the termite-fishing-rods of a chimpanzee. A bird’s wings are created directly by its genes; a bird’s nest is created indirectly by its genes, viâ the brain. So a bird’s wings are part of the phenotype and a bird’s nest part of the extended phenotype.

Both are under the influence of the genes and both are expressions of biology. Music (like bird-song) is an expression of biology too, as is the difference between the music of Erotic Support and Swords of Mars. As brains age, the behaviour they create changes. Swords of Mars are older and not attracted to reckless self-mutilation as Erotic Support were: it’s not music to precede hangovers and induce tinnitus any more. Sword of Mars aren’t trying to tattoo your ears but to educate your mind.