The Poems of A.E. Housman, edited by Archie Burnett (Clarendon Press 1997)

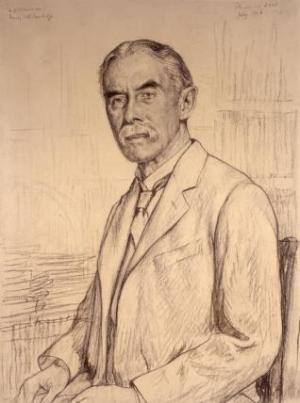

“I hate posterity — it’s so fond of having the last word.” So said Saki’s hero Reginald in “Reginald on the Academy” (1904). In The Poems of A.E. Housman, the academy is trying to have the last word on A.E. Housman (1859-1936). But Housman wouldn’t have minded. Horace boasted that his verse would prove monumentum aere perennius – “a monument more lasting than bronze” (Odes, III 30). Housman had humbler ambitions for his:

They say my verse is sad: No wonder;

Its narrow measure spans

Rue for eternity, and sorrow:

Not mine, but man’s.

This is for all ill-treated fellows

Unborn and unbegot,

For them to read

When they’re in trouble

And I am not.

In the commentary, Archie Burnett quotes a letter of “AEH to Witter Bynner, 3 June 1903: ‘My chief object in publishing my verses was to give pleasure to a few young men here and there’” (pg. 417). And Housman wasn’t in trouble when those lines were published, because he was dead. They open the posthumous More Poems (1936), which was edited by his brother Laurence.

In this case, I think there is more pleasure in the variant phrase “Tears of eternity”, included in the scholarly apparatus beneath the poem (pg. 113). Posterity seems to agree, because “Tears of eternity” appears in The Collected Poems of A.E. Housman, published as a popular edition in 1994 by Wordsworth. And it echoes Virgil’s lacrimae rerum, “the tears of things” (Aeneid, i. 462). Classical influences are not obvious in Housman, but they are there beneath the surface. The simplicity of his verse is deceptive:

Passages are adduced for consideration with no indication of their status or significance: that is a matter for literary criticism, and I have endeavoured only to provide a foundation for such criticism. I hope, however, to have rectified the anomaly whereby a wide range of intertextual reference is expected in, say, Milton or T.S. Eliot, but not in Housman; and to have promoted regard for Housman as one of the true scholar-poets. (“Introduction”, pg. lx)

Burnett’s hopes are realized. The best of Housman’s poems are like butterflies: small, delicate, enchanting. And Burnett sometimes seems to be breaking butterflies on the wheel. The commentary for a poem can be much longer than the poem itself. First it’s fixed by a long pin: “1st draft, Dec. 1895 – 24 Feb. 1900; 2nd draft 30 Mar. – 10 Apr. 1922” transfixes the lines given above, for example. Then there’s a description of the manuscripts: “ink, with corrections and uncancelled variants in pencil”. Then Burnett commences what Aldous Huxley called “the learned foolery of research into what, for scholars, is the all-important question: Who influenced whom to say what when?” (The Doors of Perception, 1954).

But the learned foolery is interesting and enlightening. You’ll understand and appreciate Housman better by reading this book. All readers will know that the lad of A Shropshire Lad (1896) is imaginary. But so, in part, is the Shropshire:

The vane on Hughley steeple

Veers bright, a far-known sign,

And there lie Hughley people

And there lie friends of mine.

Tall in their midst the tower

Divides the shade and sun,

And the clock strikes the hour

And tells the time to none. (ASL, LXI)

Burnett notes that there is “no steeple as such” on the church of St John Baptist at Hughley (pg. 365). Housman was “Worcestershire by birth” and Shropshire was his “horizon”, not his home (pg. 317). He wrote about the village of Hughley before he had even seen it:

I ascertained by looking down from Wenlock Edge that Hughley Church could not have much of a steeple. But as I had already composed the poem and could not invent another name that sounded so nice, I could only deplore that the church at Hughley should follow the bad example of the church at Brou, which persists in standing on a plain after Matthew Arnold has said it stands among mountains. I thought of putting a note to say that Hughley was only a name, but then I thought that would merely disturb the reader. I did not apprehend that the faithful would be making pilgrimages to these holy places. (Letter to Laurence Housman, 5th October 1896)

But what more appropriate for the faithful than to travel in hope and arrive in vain? A non-existent steeple is far more Housmanesque than an actual. His Shropshire is part of myth, not of mundanity. It’s a horizon, not a home, and no-one can ever go there. But if horizons are Housmanesque, so is humour. It’s not obvious from A Shropshire Lad that the author was one of the greatest classical scholars who ever lived. Nor is it obvious that the author could see the lighter side of life.

But he could. His letters prove that and so does some of his verse:

I knew a gentleman of culture

Whose aunt was eaten by a vulture.

He said “Though carrion may be scanty,

That bird should not have eaten auntie.” (?1917)

When I was born to a world of sin,

God be praised, it was raining gin,

Gin on the houses, gin on the walls,

Gin on the bunworks and copybook-stalls. (?1911)

He also joked about the Academy:

First Don O cuckoo, shall I call thee bird,

Or but a wandering voice?

Second Don State the alternative preferred,

With reasons for your choice. (date unknown)

Fragment of a Greek tragedy

Alcmaeon. Chorus.

Cho. O suitably-attired-in-leather-boots

Head of a traveller, wherefore seeking whom

Whence by what way purposed art thou come

To this well-nightingaled vicinity? (Fragment…, 1883)

The lines above are from the section called “Light Verse and Juvenilia”. Some of Housman’s nonsense verse is excellent. Some of it is also eerie: “Aunts and Nieces, or, Time and Space” (?1929) reminded me of M.R. James or Saki, with its “astoundingly absurd/Yet dangerous cockyoly-bird”:

In the middle of next week

There will be heard a piercing shriek,

And looking pale and weak and thin

Eliza will come flying in. (“Aunts and Nieces”)

Who would guess that the same man wrote A Shropshire Lad? But that also applies to “Iona”, Housman’s attempt to win the Newdigate Prize for English Verse at Oxford in 1879. As Burnett notes, the “subject and the metre (English heroic verse) were not of his choosing” (pg. 529). Unsurprisingly, the poem didn’t win the prize. It would make a good challenge for a literary scholar today. If you didn’t know who had written it, would you be able to guess?

And far in all the wide world’s peopled ways

Became a marvel and a wild amaze.

Became a wonder and a world’s desire

And fill’d high heaven and all men’s eyes with fire,

And wheresoever it smote, such power it had,

The reaper stay’d his reaping and was glad,

The ploughman left his plough and follow’d far,

The shepherd reck’d no more of folding-star,

The fisher thither turned his toiling oar

Harrowing the peopled main with nets no more.

The deep-sea diver left the watery whirl

And sought no more the shark-beleaguer’d pearl,

And far away the light on all men’s eyes

Struck blind the magian wisdom of the wise:

Then each man deemed his riches last and least

And came and worshipp’d out of west and east

At faith’s far altar raining gems like tears

And all the garner’d usury of years;

Brought jewell’d gold and treasure passing price

And ransack’d cities piled for sacrifice

And incense strange in marvellous woofs unfurl’d

For these had seen her star in all the world.

Had seen her star, and clothed in gladness trod

And walked on earth with a many a present god, […]

(“Iona”, ll. 85-108 – a “folding-star” is a star seen at nightfall, when sheep are gathered into the fold)

I think most literary scholars would conclude that those lines had been written by a forgotten Victorian poetaster influenced by Swinburne. But Burnett notes one link to Housman at his laconic best, for a reaper also appears in this poem:

Breathe, my lute, beneath my fingers

One regretful breath,

One lament for life that lingers

Round the doors of death.

For the frost has killed the rose,

And our summer dies in snows,

And our morning once for all

Gathers to the evenfall.

Hush, my lute, return to sleeping,

Sing no songs again.

For the reaper stays his reaping

On the darkened plain;

And the day has drained its cup,

And the twilight cometh up;

Song and sorrow all that are

Slumber at the even-star.

When I first came across that on the internet, I thought it was a late poem. It actually pre-dates “Iona” and was written in 1877 as a “song for Lady Jane Grey awaiting death in captivity”, part of a play, The Tragedy of Lady Jane Grey, that would have been published in a “Family Magazine”. But Housman left home to attend Oxford before he finished editing and transcribing the magazine.

Only a “fragment” of it was left and that is how the poem survived. What else has been lost? Nothing better than that, I would guess – and hope. But in a way this book retrieves lost poems. In the commentary to Poem XXV of Last Poems (1922), Burnett parallels Housman’s “sea-wet rock” with Philip Bourke Marston’s “sea-wet shining sand”. Marston was a blind poet whose collection Song-Tide (1888) was a “volume in Housman’s library”. He deserves to be better-remembered.

The German poet Heine, on the other hand, has the modern fame he deserves: a lot. His influence on Housman was considerable and he often appears in the commentary. Take Poem LVII in A Shropshire Lad:

You smile upon your friend to-day,

To-day his ills are over;

You hearken to the lover’s say,

And happy is the lover.

’Tis late to hearken, late to smile,

But better late than never;

I shall have lived a little while

Before I die for ever. (ASL, LVII)

The commentary notes a parallel with these verses by Heine:

Es kommt zu spät, was du mir lächelst,

Was du mir seufzest, kommt zu spät!

Längst sind gestorben die Gefühle,

Die du so grausam einst verschmäht.

Zu spät kommt deine Gegenliebe!

Es fallen aus mein Herz herab

All deine heissen Liebesblicke

Wie Sonnenstrahlen auf ein Grab.

Then it quotes the stilted Victorian translation Housman was familiar with: “It comes too late, thy present smiling, | It comes too late, thy present sigh! | The feelings all long since have perish’d | That thou didst spurn so cruelly. || Too late has come thy love responsive, | My heart thou vainly seek’st to stir | With burning looks of love, all falling | Like sunbeams on a sepulchre.” That’s by Edgar Alfred Bowring. Housman captures the simplicity and spirit of Heine much better in A Shropshire Lad.

But “Breathe, my lute” proves that Housman was Housmanesque before Heine, whose influence is “later than 1889” (“Introduction”, lx). Shakespeare and the Bible influenced him from the beginning, as the commentary proves again and again. He was also influenced by English and French folk-ballads, by Tennyson, Christina Rosetti, Swinburne and Stevenson, and by classical authors like Horace, Lucretius, Juvenal and Propertius. Burnett quotes the original languages, noting the Greek πολυφαρμακος behind “many-venomed” in Poem LXII of A Shropshire Lad and expanding Poem XLIII of More Poems with a resounding phrase from Lucretius: moles et machina mundi, “the mass and fabric of the world” (pg. 455).

And Propertius might have been writing Housman’s epitaph here:

Qui nunc iacet horrida pulvis,

Unius hic quoniam servus amoris erat. (Elegies II. XiiiA. 35-6)

Those lines were noted as a parallel to Poem XI of A Shropshire Lad by the Japanese scholar Tatsuzo Hijakata in the Housman Society Journal (9, 1983). Again the translation given here is stilted: “He that now lies naught but unlovely dust, once served one love and one love only”. Housman captured the spirit and simplicity of Propertius far better:

On your midnight pallet lying,

Listen, and undo the door:

Lads that waste the light in sighing

In the dark should sigh no more;

Night should ease a lover’s sorrow;

Therefore, since I go to-morrow,

Pity me before. (ASL, XI)

The classical influence could be more indirect: “the bluebells of the listless plain” in XXVIII of More Poems are explained by the parallel between the flower’s scientific name, Campanula, “little bell”, and campania, “level plain” (pg. 444). And so the spirit of Housman, “amateur botanist and professional Latinist” (ibid.), lingers amid the “learned foolery”, which cannot explain why his poetry is so good, but can illuminate his sources and allow people who knew him to reveal some of his contradictions and complexities:

One morning in May, 1914, when the trees in Cambridge were covered with blossom, he reached in his lecture… “Diffugere nives, redeunt iam gramina campis.” This ode [Horace, IV 7] he dissected with the usual display of brilliance, wit and sarcasm. Then for the first time in two years he looked up at us, and said in quite a different voice: “I should like to spend the last few minutes considering this ode simply as poetry.” Our previous experience of Professor Housman would have made us sure that he would regard such a proceeding as beneath contempt. He read the ode aloud with deep emotion, first in Latin and then in an English translation of his own. “That,” he said hurriedly, almost like a man betraying a secret, “I regard as the most beautiful poem in ancient literature,” and walked quickly out of the room. A scholar of Trinity (since killed in the War), who walked with me to our next lecture, expressed in undergraduate style our feeling that we had seen something not really meant for us. “I felt quite uncomfortable,” he said. “I was afraid the old fellow was going to cry.” (Commentary on More Poems, Poem V, pg. 427, quoting Mrs T.W. Pym in The Times, 5th May 1936, 5, from Grant Richards, Housman 1897-1936 (revised edition 1942), pg. 289)

But one of those who knew Housman was Housman himself. In More Poems XLIV, he writes of “Venice under sea”. And here, in a letter to his sister Katharine in 1926, is his last word on his love for the city:

I was surprised to find what pleasure it gave me to be in Venice again. It was like coming home, when sounds and smells which one had forgotten stole upon one’s senses; and certainly there is no place like it in the world: everything there is better in reality than in memory. I first saw it on a romantic evening after sunset inn 1900, and I left it on a sunshiny morning, and I shall not go there again. (Commentary to MP, XLIV, pp. 456-7)

Housman’s life, like his verse, combined contradictions: the bitter with the sweet. Sometimes he felt that everything had been futile:

When the bells justle in the tower

The hollow night amid,

Then on my tongue the taste is sour

Of all I ever did. (Additional Poems (1939), IX)

But that is actually “A Fragment preserved by oral tradition and said to have been composed by A.E. Housman in a dream” (pg. 469). Housman himself said that he did “not know” it or had “forgotten” it. So he forgot what he dreamt. He remembered what he had lived and could mingle the sweetness of memory with the bitterness of loss:

’Tis time, I think, by Wenlock town

The golden broom should blow;

The hawthorn sprinkled up and down

Should charge the land with snow.

Spring will not wait the loiterer’s time

Who keeps so long away;

So others wear the broom and climb

The hedgerows heaped with may.

Oh tarnish late on Wenlock Edge,

Gold that I never see;

Lie long, high snowdrifts in the hedge

That will not shower on me. (ASL, XXXIX)

Previously pre-posted (please peruse):

• Poetry and Putridity — A.E.H. vs C.A.S.