An Adventure in Multidimensional Space: The Art and Geometry of Polygons, Polyhedra, and Polytopes, Koji Miyazaki (Wiley-Interscience 1987)

An Adventure in Multidimensional Space: The Art and Geometry of Polygons, Polyhedra, and Polytopes, Koji Miyazaki (Wiley-Interscience 1987)

Two, three, four – or rather, two, three, ∞. Polygons are closed shapes in two dimensions (e.g., the square), polyhedra closed shapes in three dimensions (the cube), and polytopes closed shapes in four or more (the hypercube). You could spend a lifetime exploring any one of these geometries, but unless you take psychedelic drugs or brain-modification becomes much more advanced, you’ll be able to see only two of them: the geometries of polygons and polyhedra. Polytopes are beyond imagining but you can glimpse their shadows here – literally, because we can represent polytopes by the shadows they cast in 3-space or by the shadows of their shadows in 2-space.

A four-dimensional shape in two dimensions (see Tesseract)

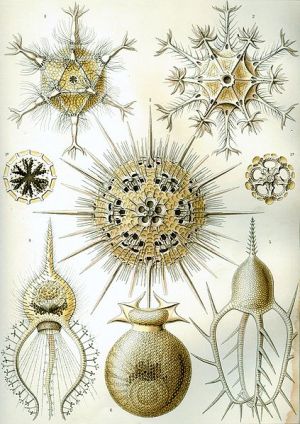

Elsewhere Miyazaki doesn’t have to convey wonder and beauty by shadows: not only is this book full of beautiful shapes, it’s beautifully designed too and the way it alternates black-and-white pages with colour actually increases the power of both. It isn’t restricted to pure mathematics either: Miyazaki also looks at the modern and ancient art and architecture inspired by geometry, and at geometry in nature: the dodecahedral pollen of Gypsophilum elegans (Showy Baby’s-Breath), for example, and the tetrahedral seeds of the Water Chestnut (Trapa spp.), which the Japanese spies and assassins called the ninja used as natural caltrops. A regular tetrahedron always lies on a flat surface with a vertex facing directly upward, and when a pursued ninja scattered the sharply pointed tetrahedral seeds of the Water Chestnut, they were regular enough to injure “the soles of feet of his pursuers”.

Polyhedral plankton by Ernst Haeckel

The slightly odd English there is another example of what I like about this book, because it proves the parochialism of language and the universality of mathematics. Miyazaki’s mathematics, as far as I can tell, is flawless, like that of many other Japanese mathematicians, but his self-translated English occasionally isn’t. Japanese mathematics was highly developed before Japan fell under strong Western influence. It would continue to develop if the West disappeared tomorrow. Language is something we have to absorb intuitively from the particular culture we’re born into, but mathematics is learnt and isn’t tied to any particular culture. That’s why it’s accessible in the same way to minds everywhere in the world. Miyazaki’s pictures and prose are an extended proof of all that, and the book is actually more valuable because it was written by a Japanese speaker. I think it’s probably more attractively designed for the same reason: the skill with which the pictures have been selected and laid out reflects something characteristically Japanese. Elegance and simplicity perhaps sum it up, and elegance and simplicity are central to mathematics and some of the greatest art.

Another four-dimensional shape in two dimensions (see 120-cell)